Parliamentary Elections in Transnistria: Internal and External Dynamics, Including Rising Tensions with Moldova and the Influence of Russia

Elections without choice

The parliamentary elections scheduled for 30 November in Transnistria mark the beginning of a year-long electoral cycle that will conclude with the presidential elections in December 2026. Under an oligarchic model of governance, in which key state institutions are controlled by the “Sheriff” holding, the parliamentary elections did not become an example of competition among candidates and their programs. Only 53 candidates were registered for 33 parliamentary seats, and in 22 districts a single non-competitive candidate was registered. This situation of “elections without choice” indicates not system stability, but its high degree of administrative control. Even though 11 new deputies will join the Supreme Council, this renewal is not competitive but administrative, reinforcing a low level of internal legitimacy and generating a negative perception among a significant part of the population.

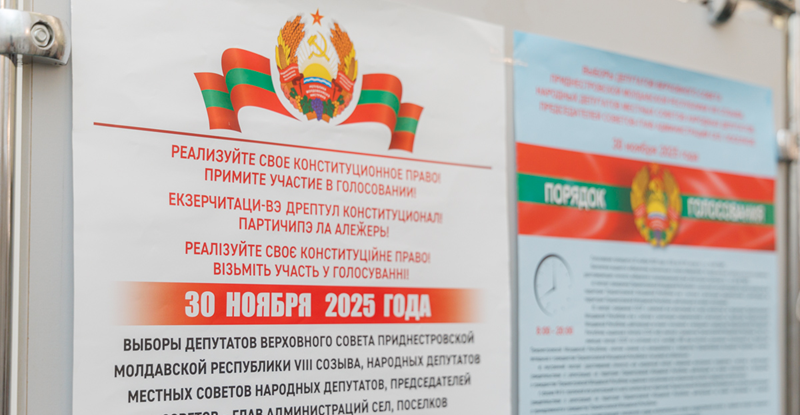

Image: Poster calling for people to use their constitutional right (Source: Novosti Pridnestrovya)

Image: Poster calling for people to use their constitutional right (Source: Novosti Pridnestrovya)

From a research perspective, the elections are significant because they allow the identification of potential candidates for the presidency of Transnistria. Traditionally, the position of parliamentary speaker has served as a political springboard in the year preceding a presidential campaign; this was the path of Igor Smirnov, Yevgeny Shevchuk, and Vadim Krasnoselsky. However, the current political configuration suggests that the incumbent speaker, Alexander Korshunov, despite his strong chances of re-election as a deputy and possibly speaker, is not viewed as the natural successor for the presidency. Instead, a new candidate is likely to emerge from the government or from among the mayors of major cities –Tiraspol and Bender. Potential contenders include Alexander Rosenberg, head of the Transnistrian government; Ilona Tyuryaeva, mayor of Tiraspol, the capital of Transnistria; and Vitaly Neagu, Minister of Internal Affairs. It is also likely that Moscow will seek to promote its own candidate, whom several experts believe to be Vitaly Ignatiev, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Transnistria.

Source: Vitaly Ignatiev, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Transnistria (Source: Novosti Pridnestrovya)

Such a managed electoral process is convenient for the authorities, but it significantly increases risks for Tiraspol amid EU-supported reintegration efforts. Following the parliamentary elections of 28 September 2025, in which the PAS party secured a new majority, Chisinau began discussing a “reintegration plan” for Transnistria with Brussels. This dynamic is likely to become a key driver of rising tensions between Moldova and Russia over the next two to three years.This timeframe is linked to political commitments made by Moldova’s leadership, according to which the country must complete accession negotiations with the European Union by 2028 and become a full EU member by 2030. Another temporal constraint is Moldova’s local elections scheduled for 2027, which will divert political attention from Transnistrian affairs. Thus, the Moldovan government effectively has two and a half to three years to design and implement its reintegration strategy.

Problems of reintegration

During his visit to Brussels on 17–18 November 2025, Prime Minister Alexei Muntean announced that discussions were underway in Chisinau on a “reintegration plan” with the United States and the European Union. Although the details were not disclosed, statements by Deputy Prime Minister for Reintegration Vitali Kiveri indicate that the government will focus primarily on economic instruments. This approach is not new: economic leverage has long been used by Chisinau to extend its legal framework to Transnistrian businesses. This strategy reached its peak after the outbreak of war in Ukraine in 2022. Transnistria became cut off from traditional logistical routes through Ukraine, and today all foreign economic transactions are processed through Moldovan customs.

The Moldovan authorities, however, view this economic reality positively in terms of reintegration, since Transnistria’s economy is increasingly integrated with the European market. Today, around 80% of Transnistrian exports go to the EU – apercentage higher than Moldova’s national average of 65%. Additionally, more and more young Transnistrians choose to study and work in the EU, seeing Europe not as a threat but as an opportunity for social mobility. This economic and educational shift becomes, for Chisinau, an argument that reintegration may occur through mechanisms of “silent integration,” without rapid political decisions.

Image: Economic crisis affects public sector payments in Transnistrian rubles (Source: Novosti Pridnestrovya)

Socially, the situation in Transnistria deteriorated significantly after 1 January 2025, following the end of Russian gas transit through Ukraine. Factory shutdowns, business closures, and growing insecurity among residents created, in Moldova’s view, favorable conditions for reunification. Politically, however, a stalemate has emerged. Moscow cannot re-activate the 5+2 format, which Kyiv and Chisinau regard as dysfunctional, while Moldova, Ukraine, together with the EU and the United States, cannot yet propose a new negotiation model. The conflict has shifted to a symbolic level, where European integration in Moldova is perceived as a victory over Russia rather than an expansion of stability. In this context, relations between Chisinau and Tiraspol have transformed from a search for mutually acceptable solutions into a system of unilateral notifications.

The Russian factor

Despite total economic control over Transnistria, Chisinau has not succeeded in gaining political influence over institutions on the left bank. Moreover, the opposing sides now follow fundamentally different geopolitical paths. While Moldova has firmly chosen EU integration, Tiraspol remains embedded within a Russian ideological system. This makes the conflict particularly acute.

During the first meeting of the new Moldovan government on 5 November, decisions were made to close the Russian Center of Science and Culture and later to terminate the visa-free regime with Russia. According to Foreign Minister Mihai Popșoi, Moldova will gradually comply with EU requirements and introduce a visa regime for Russian citizens. Such decisions significantly reinforce distrust of Chisinau among Transnistrian citizens, for whom Moscow is a key strategic partner.

A notable diplomatic conflict further illustrates the situation: for more than two years, Russia’s appointed ambassador, Oleg Ozerov, has remained unaccredited in Moldova. Chisinau refuses to accept his credentials but regularly summons him to deliver diplomatic notes of protest. This paradox reflects the current stance: Moldova minimizes institutional interaction with Russia while actively using diplomatic channels to express grievances. Such a model of low engagement combined with high confrontation deepens mistrust and complicates any negotiation format, including those related to reintegration.

Economically, Russia continues to provide financial assistance to Transnistria, effectively paying for gas supplies to the region via international intermediaries. In this context, Chisinau appears to commit a conceptual error by assuming that Transnistria’s economic dependence on Moldova will inevitably result in political loyalty. The formula “no gas – no economy – no state” is convenient for propaganda, but it does not match reality. Transnistria’s resilience stems from high social adaptability in conditions of uncertainty. The growth in the number of Transnistria’s Moldovan passport holders (over 300,000 people) is not a political choice in favor of Europe but a survival-driven strategy expanding opportunities while retaining Russian or Ukrainian identity options.

Image: Transnistrian passport is valid only in Republic of Moldova to provide freedom of movement. Many residents hold more than two citizenships that facilitate their external mobility (Source: Eiki Berg)

It is equally telling that Moldova is almost entirely absent from Transnistria’s symbolic and cultural space. The celebration of the 617th anniversary of Bender this year passed without any official greeting from Moldovan politicians. This reflects not hostility but indifference. Reintegration begins not with documents but with presence. As long as Chisinau remains absent from regional public life, any plans will remain declarative.

Russia maintains its influence in Transnistria not only through economic resources but through symbols. The 1992 peacekeeping mission and the control of the Cobasna arms depot serve as symbolic markers of Russia’s sphere of responsibility. Any attempts to discuss the withdrawal of Russian forces without Russia’s participation will inevitably provoke a harsh response. A direct military escalation remains unlikely: Ukraine has no interest in opening a new front; the EU aims to avoid destabilization; and Moldova lacks the resources and mandate for military action. However, minor incidents cannot be ruled out. Such incidents could be used as instruments of leverage, especially in moments of broader regional insecurity.

Image: Peeking into the minister’s office at the MFA, Transnistria (Source: Eiki Berg)

The situation remains in a state of dynamic equilibrium. Despite maintaining control over the region, Russia is gradually losing its monopoly on narratives and meanings. Russia now competes less with Chisinau and more with the EU and the United Kingdom for influence over young people, educational opportunities, digital networks, and the future identity of the region. The defeat of pro-Russian parties in the 2025 Moldovan elections highlights a crisis in Russia’s regional agenda. Traditional approaches no longer work, and Moscow has yet to formulate new tools. If Russia continues to perceive Transnistria only as a space of control rather than modernization, it will lose its long-standing advantage – namely, in the field of ideas.

Outlook

Given the EU’s interest in keeping Moldova on the European path, Brussels is expected to play a more active role in financing reintegration. Some funds may be provided as part of Ukraine’s post-war reconstruction. According to Speaker Igor Grosu, reintegration financing should amount to €0.5 billion annually. Yet such funding is feasible only as part of a long-term European package spanning 10–15 years and including loans, grants, and reforms. It is clear that the EU and the United States will not finance reintegration as a stand-alone initiative: instead, reintegration will occur as part of Moldova’s integration into the EU, with a special policy framework for the left bank.

Ultimately, the parliamentary elections in Transnistria open a new stage in the region’s development amid Moldova’s expected EU accession negotiations. Tiraspol must either demonstrate that it is not merely a “territory without gas” but a socio-political organism capable of surviving external shocks while awaiting the outcome of the war in Ukraine, or it will face an accelerated process of gradual integration into Moldova’s legal system. Chisinau’s path is already clear. The key intrigue lies in Moscow’s future actions. If Russia does not initiate political modernization in Transnistria, its influence will become nominal, and the region’s value system will increasingly be shaped by other actors. The future of the region will be determined not by pressure, but by the attraction of the development model offered – and the actor that articulates the most convincing model will define the architecture of post-conflict Moldova.

Author: Anatolii Dirun