Overview of 2024: De Facto States Clinging to Sovereignty

The De Facto States Research Unit looks once again back at the developments in the lesser recognised world in 2024, this time focusing on a smaller selection of these entities. Continuing the trends summarised in our previous overviews (2020, 2021, 2022, 2023), 2024 brings yet more uncertainty to these actors, with several of them expressing fears of becoming increasingly sidelined in the regional and great power competition. Despite the increased external – and in some cases internal – turbulence, all de facto states cling stubbornly to their at least nominal independence, with none of them showing readiness to engage in meaningful peace talks. While in the 2022 overview we predicted that the ongoing realignment of international power dynamics might foment new secessionist movements and perhaps even the creation of new de facto states, this prediction has not come true, with only Bougainville currently pursuing secession consistently, but also threatening to declare unilateral independence should the process become stalled much longer. While the continued existence of current de facto states seems to become more precarious in longer term, they are likely to manage holding on for 2025.

The Autonomous Region of Bougainville

Bougainville continues its journey towards independence from Papua New Guinea (PNG), which it hopes to achieveas early as 2025 or by 2027 at the latest. In March, the Bougainville constitutional commission releases the first draft of a new constitution, developed over two years of extensive consultations. Further consultations follow, both locally and among diaspora communities, with international consultations held in June in the Solomon Islands, and August in Brisbane, Australia. Bougainville’s president Toroama reaffirms the commitment to independence in June, as the autonomous government continues to lay out new laws and strategies in preparation. In July, Bougainville launches an external relations directorate, welcomed by the PNG prime minister as an important step. According to the 2001 Bougainville Peace Agreement, Bougainville has the right to engage externally on trade and regional relations, and the directorate’s first priority is to become an observer in the Melanesian Spearhead Group, a sub-regional grouping created in 2007 to promote economic growth.

However, significant challenges remain. The PNG parliament is yet to table Bougainville’s 2019 independence referendum results. The conditions under which MPs would vote on ratification remain the major sticking point: Bougainville argues that a simple majority suffices, whereas PNG insists on an absolute majority. As the political process falters, Bougainville warns that it might bypass the PNG parliament entirely, and declare independence once the new constitution is completed. However, for now, Bougainville is committed to seeking a solution with PNG, requesting an international mediator to be brought in to help solve the impasse. In May, PNG government agrees, and in September, Sir Jerry Mateparae, former New Zealand governor-general and a senior diplomat with previous involvement in the Bougainville peace process, is announced as the moderator. He proceeds to meet with both sides, and carries out a more extensive visit to Bougainville at the end of November along with UN representatives. Still, 2024 ends with no tangible progress on solving the issue.

Bougainville must also consider its economic future, as it currently relies heavily on PNG budget allocations, with internal revenues covering only about seven percent of the budget. Bougainville puts most of its economic hopes on mining, including reopening the controversial Panguna mine, which holds an estimated 60 billion USD of untapped copper deposits. Initial steps on this front are promising: in February, the government gives a five-year extension of its exploration licence for the Panguna mine to Bougainville Copper Limited (BCL), now under the majority ownership of the government itself, and organises an extensive engagement programme to gain approval of local landowners. Simultaneously, the government aims to curb small-scale mining, announcing that after October 21, all mining activities carried out by locals without a mineral licence are illegal. Towards the end of November, 300 traditional landowners from the area sign a Land Access and Compensations Agreement with BCL, signalling their approval of the exploration plans in what the government hails as tangible progress on reopening the mine. Additionally, a Canadian company begins a mining exploration programme in March on Bougainville’s main island, prospecting for gold and copper in what is the first large-scale mineral exploration programme in Bougainville outside of the Panguna mine in decades. In December, another Canadian company reports that it is beginning phase four of an exploration programme at another site located near the Panguna mine. Their first phases of exploration indicate the presence of gold, silver, copper, molybdenum, and base metals. Throughout the year, Toroama also expresses that Bougainville is ready to engage with whatever nations are available for international business, including China. He admits there has been little interest from the US or Japan, despite his efforts to target the US specifically and inviting them to also consider establishing a military base in Bougainville, but there is some engagement with Australia. Chinese corporations have visited Bougainville, but without making specific commitments so far. Small economic relief is brought to the region through the high cacao prices on the world market, bringing much-welcomed profits to the Bougainville farming communities this year, and leading to a small economic boom in the area. Accordingly, Bougainville’s annual chocolate festival, held in September, is bigger than ever.

Image: Bougainville farmer showing cash he got for his cocoa crops. Source: https://x.com/tambijr_4rmPNG/status/1726498134963155112

Work continues in 2024 to address environmental damage from the Panguna mine. Rio Tinto and BCL, the owners of the Panguna mine at the time of its abandonment due to the civil war in 1989, have agreed to fund an independent assessment for determining the extent of the environmental damage, with the report due towards the end of the year. But locals are frustrated by the lack of commitment to compensation or cleanup, leading Bougainvilleans to call for Rio Tinto to set “concrete commitments for remediation and clean up” at the end of February. Some progress is achieved, as in August and ahead of publishing of the report, BCL and Rio Tinto agree to plans to remove ageing infrastructure from the mine site to address safety issues. But a class action lawsuit against Rio Tinto and BCL over the environmental issues and social destruction caused by the Panguna mine, filed in May in the PNG court, adds complexity. The action is led by Martin Miriori, brother of Bougainville’s first president and former rebel leader, but backed by anonymous offshore investors. The lawsuit creates a lot of controversy in Bougainville: backers worry that while Rio Tinto is funding the environmental assessment report, it has not indicated readiness to act and offer compensation. The lawsuit would then be a way to remedy that. Critics worry it could hinder mine revival and undermine environmental assessment efforts, since Rio Tinto could view the assessment as a tool that could be used against them in the courtroom. Additional worries include that the inclusion of anonymous sponsors could eventually leave Bougainvilleans empty-handed. Bougainville’s president Toroama says the lawsuit is disappointing and the work of people not acting in the interests of Bougainville as a whole, and the action does not have the government’s backing as it is hindering Bougainville’s economic independence agenda.

Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (Western Sahara)

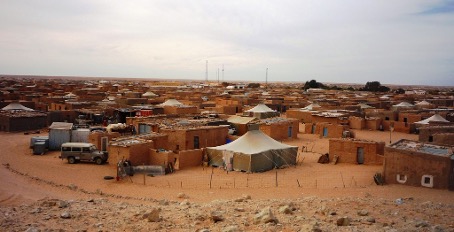

SADR begins 2024 with an annual Foreign Relations Conference, where president Brahim Ghali calls for the expansion and improvement of SADR’s “diplomatic offensive”. Indeed, the year is marked by a number of foreign visits, including to Ireland, to the African Union Summit in Ethiopia, or to East Timor where he also meets the UN secretary-general, as well as hosting foreign dignitaries, such as the delegation from the European parliament, or the personal envoy of the UN secretary-general for Western Sahara, Staffan de Mistura. But among these displays of diplomatic engagements are also more worrying signs of a slipping international standing. In March, Ghali contacts the UN in relation to reports in the Spanish media that Spain intends to transfer the management of Western Sahara’s air space over to Morocco: according to Western Sahara, this violates Spain’s obligations as the administering state of Western Sahara. In July, it is revealed that France is switching its support to Morocco’s claim on Western Sahara, and is supporting offering autonomy to Western Sahara under Moroccan sovereignty as the basis of achieving a lasting solution. Polisario Front condemns the decision, and promises that the Sahrawi people will “continue to stubbornly defend their rights” until independence is achieved. Their main supporter Algeria recalls its ambassador to France over the decision, and starts to refuse Algerian nationals deported from France. In August, Chad opens a consulate in Morocco-ruled Western Sahara, joining 28 other African and Arab countries that have established diplomatic missions in what Morocco calls its “Southern Provinces” as a sign of support for Morocco’s claim. The Polisario Front protests the opening of the consulate general in a letter to the UN secretary-general.

According to the annual report of the UN Secretary-General, delivered in October 2024, the situation in Western Sahara continues to be characterised by tensions and low-intensity hostilities between Morocco and the Polisario Front, with little progress in conflict resolution despite the efforts of Staffan de Mistura, the UN secretary-general’s personal envoy for Western Sahara. The Polisario Front accuses Morocco in escalating its scorched earth policy, including tactics of demolishing and burning down the homes of Sahrawi families in the territories under Morocco’s control, and allowing more Moroccan settlers in the territory. In response, the Polisario Front reiterates that the Sahrawi people will continue fighting, repeating this message in formal speeches, in meetings, as well as in letters to the UN secretary general through the year. Ghali even calls for the Polisario Front to “escalate and advance the armed struggle” in May. UN’s MINURSO mission continues to receive reports about shootings by the Polisario Front, Moroccan air strikes, and observes new Moroccan military camps set up as “preventive and provisional measures” to protect Moroccan army units.

Another worrying issue is the continued targeting, intimidation, and surveillance faced by Sahrawi human rights activists in Morocco. In April, it emerges that they have been targeted by new mobile malware masquerading as a legitimate news app while stealing information from the targets device. Morocco tries to shift blame by pointing to the alleged human rights violations in the Tindouf refugee camps for the Sahrawi people, claiming that there are severe restrictions on fundamental freedoms. UN Fourth Committee’s (Special Political and Decolonization) meeting with petitioners for Western Sahara in October sheds some light on the civil society perspective on Western Saharan issues, unveiling a mixed reality on the ground. While Morocco is painted as an occupant by some, the activists are not pleased with the Polisario Front’s activities, either, highlighting its role in perpetuating the conflict and its negative effects on ordinary people. There are also claims that some Sahrawi tribes consider themselves as strongly bonded with Morocco and would welcome the autonomy initiative, while the Polisario Front holds the Sahrawi people hostage in refugee camps that resemble open-air prisons.

Image: Sahrawi refugee camp in Tindouf region of Algeria (Source: Borgen Magazin)

While some claim that after France’s support of Morocco’s claim over Western Sahara, the conflict is over and the Sahrawi people have no choice but to settle for some form of autonomy within Morocco, the Polisario Front receives a diplomatic and legal victory in October, when the European Court of Justice, the top court of the EU, upholds earlier rulings that Western Sahara’s status as a non-self-governing territory means that the EU cannot include the territory in bilateral agreements with Morocco and that consent on entering into agreements relating to their territory needs to be obtained from the Sahrawi people. The court also rules that melons and tomatoes produced in Western Sahara must now have their origin labelled as such. The decision effectively cancels the 2019 EU-Morocco trade deals that allowed Morocco to export fish and farm products from Western Sahara to the EU, as well as prohibits EU fishermen from fishing in either Western Saharan or Moroccan waters. The decision also means that the EU must open direct talks with the Polisario Front, should it wish to reach a trade deal. While Morocco condemns the decision and the EU Commission promises to examine it, the Polisario Front hails it as a “historic victory”. The Court’s decision seems to clash with the plans of the French delegation visiting Morocco later in the same month: during the visit, French president Macron unveils investment plans in Western Sahara as part of a broader package of bilateral agreements and partnerships with Morocco.

One more idea emerges from the UN for conflict resolution in October. During a closed security council meeting, the UN special envoy for Western Sahara floats the idea of dividing the territory between Morocco and the Polisario front as one potential solution to the conflict. According to de Mistura, such action would allow the creation of an independent state in the southern part of Western Sahara, while the other part could be properly integrated with Morocco. At the same time, he admits that both sides reject this proposal, adding that the UN secretary general should reconsider his role as an envoy unless some progress is made within the next six months. De Mistura also calls on Morocco to better explain and expand on its autonomy plans for Western Sahara. Feeling that despite the recent legal victory at the European Court of Justice, control of the disputed territory is slipping out of its hands, the Polisario Front ends the year by vowing to intensify the armed struggle.

The Republic of Somaliland

On January 1, 2024, Ethiopia and Somaliland sign a memorandum of understanding (MoU), expressing intent of future cooperation. While the exact details are not publicised, leading to some confusion as to what the two sides actually agreed on, it is widely reported that Somaliland has promised landlocked Ethiopia future use of its ports, and possibly lease Ethiopia a 20 km section of its coast for military use. In return, it is reported that Somaliland would get a share in the state-owned Ethiopian Airlines, and most controversially, recognition. Ethiopia is not willing to confirm the latter promise, instead talking about making “an in-dept assessment towards taking a position regarding the efforts of Somaliland to gain recognition”. Somalia reacts quickly, calling the signing of the MoU an act of aggression by Ethiopia and warning that the deal endangers regional stability while its people are asked to prepare for the defence of the country. On 8 January, the army chiefs of Somaliland and Ethiopia meet to discuss possible military cooperation, though once again, no further details are given, but the next Ethiopian-Somaliland meeting is cancelled when Somalia turns away the plane transporting Ethiopian officials.

The deal with Ethiopia is not only controversial externally, but also internally: Somaliland’s defence minister resigns in protest over the signing of the MoU, and his home region or Awdal threatens to rise up. Following a year of unprecedented turmoil for Somaliland, including significant losses to SSC-Khatumo forces in August 2023 that challenged Somaliland’s narrative of effective control and governance of the secessionist territory, this is bad news for Somaliland’s president Muse Bihi Abdi, who is accused in trying to deflect attention away from domestic issues. In February, elders of the Lughaya district vehemently oppose the MoU, and declare allegiance to Somalia. The wider public reaction in Somaliland is similarly negative, with many viewing the possible lease of land to Ethiopia as compromising Somaliland’s sovereignty.

After Somalia approves a pivotal defence and maritime economy development agreement with Türkiye at the end of February, Somaliland promises to continue pursuing cooperation with Ethiopia and continue interfering with Somali airspace, posing significant risks not only to regional safety, but also to civil aviation safety. International community backs Somalia’s territorial integrity and intervenes to lower the tensions. Türkiye organises talks in Ankara in July, but Ethiopia is not willing to back down from the deal with Somaliland. However, things turn sour again from Somaliland’s perspective when, during subsequent talks in December, Ethiopia and Somalia agree to respect one another’s sovereignty, and to strive towards mutually beneficial agreements granting Ethiopia sea access under Somalia’s sovereignty. Still, Somaliland remains somewhat optimistic regarding their international prospects. Significantly, it is hoped that the incoming Trump administration in the US might revisit the recognition issue, as some US department of state officials working on Africa policy during his first term have publicly voiced support for recognising Somaliland.

Somaliland’s carefully cultivated image as a unified, de facto independent state continues to unravel when, during the summer, Djibouti endorses the Awdal State Movement (ASM) which opposes Somaliland’s secession from Somalia, and hosts ASM’s representatives. Two weeks later, Djibouti also hosts the head of the interim authority of SSC-Khatumo – which holds about a fifth of the territories claimed by Somaliland. Djibouti’s actions of exacerbating the internal divisions in Somaliland indicate a change in direction, as previously, the country has supported Somaliland’s internal cohesion and stability. The change seems to be a response to the Ethiopia-Somaliland MoU, as this cooperation threatens Djibouti’s revenues received through their port being the primary gateway for Ethiopian goods.

These developments do not look promising for president Bihi, who is facing elections this year. As the presidential elections were initially supposed to be held in 2022, but were postponed repeatedly, critics and the opposition worry that Bihi might use the ongoing internal disputes as excuse to postpone the elections once again. Some also worry that the government might prepare for another round of confrontations with SSC-Khatumo in May. But both fears turn out to be unfounded, and the elections take place in November. The main challenger of president Bihi and his ruling Kulmiye (Peace, Unity and Development) party is the former parliamentary speaker Abdirahman “Irro” Mohamed Abdullahi of the Somaliland National Party, also known as the Wadani party, which has promised more roles for women and young people in his government. Rising cost of living and territorial tensions have emerged as key issues in the run-up to the election. Irro also promises during the campaign to review the deal with Ethiopia. Irro does end up winning with 64% of the votes, while Bihi receives 35%. Critics say that Bihi lost support due to his paternalistic style and dismissing the public opinion. Irro is seen as a more unifying, less militaristic figure. Still, he is unlikely to abandonSomaliland’s quest for recognition and statehood, and while cooperation with Ethiopia remains in limbo, he is quick to ensure he’ll continue Somaliland’s relations with Taiwan.

Republic of Abkhazia

2024 was an especially turbulent year for Abkhazia, marked by legislative conflicts and widespread protests, strained relations with Russia, economic and energy struggles, and mass protests leading to the resignation of President Aslan Bzhania. The government proposed 46 legislative changes aimed at harmonizing Abkhazian law with Russian regulations. Among the most controversial were: Foreign Agents Law (February) which allowed organizations as well as individuals to be classified as foreign agents, viewed as a tool for suppressing dissent. Apartments Law (July) would have permitted foreign citizens to buy property in Abkhazia, which is banned by the Abkhazian Constitution. The law caused widespread protests which led to the bill being withdrawn. Presidential Oversight Law (March) limited the president’s power to sign foreign agreements without parliamentary approval. This bill was motivated by the increasing tendency of Bzhania government to make deals unbeknownst to the public, as illustrated by the controversy around the Pitsunda State Dacha issue. Finally, the Defamation Law (April) proposed harsher penalties for criticizing the government but was ultimately rejected by the parliament.

Bzhania’s government faced severe backlash over these policies, leading to increased tensions between the administration and parliament. The final drop in the bucket was the introduction of the controversial Russian investment agreement to the parliament on October 7. Abkhazia signed the agreement without parliamentary approval on October 30. On November 12, mass protests erupted over the agreement granting Russian businesses tax breaks and investment privileges. Protesters stormed the parliament, uncovering documents exposing corruption, secret restrictions on naturalization for Turkish-Abkhazians and blacklists of opposition figures. Amid mounting pressure, Bzhania resigned on November 19, fled to Russia and the parliament voted against the investment agreement on December 3. Vice President Badra Gunba assumed the role of acting president until the 2025 elections. The political controversies of 2024 did not end with Aslan Bzhania, though. Abkhazia’s Foreign Minister Inal Ardzinba hosted a TV show on Russian state media, an action which led to criticism. Foreign Minister Ardzinba was dismissed and placed under travel restrictions as a result of the backlash. Sergey Shamba succeeded him. Another political scandal occurred when a parliamentary session on banning cryptomining turned violent with an MP shooting and killing one colleague and wounding another.

Image: Protesters storming the parliament building in Sukhumi, Nov 12, 2025 (Source: Al Jazeera)

Despite positioning himself as Russia’s closest ally, Bzhania struggled to secure Moscow’s full support. Early in the year, rumours surfaced that Russia might strip Abkhazian activists of Russian citizenship. In August, leaked minutes of a meeting revealed that Russia demanded key pro-Russian reforms in exchange for continued financial aid. By September 1, Russia suspended socio-economic assistance, significantly impacting Abkhazia’s budget. Meanwhile, concerns grew over a possible Russian-Georgian agreement that could restore Georgia’s territorial integrity through a (con)federal model. While Abkhazian officials dismissed this possibility, they acknowledged that Moscow’s growing ties with Tbilisi created uncertainty. Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov’s comments in September, suggesting Russia could facilitate normalization between Georgia and Abkhazia, further fuelled these fears. Contrary to all the tension, in the March 17 Russian presidential elections Abkhazians voted overwhelmingly for Putin (94%). Failing to return the favour, Putin did not congratulate Abkhazia on its independence anniversary on August 26, breaking tradition.

Adding more tension to the equation was the unprecedented energy crisis faced in Abkhazia. Russian electricity supply ceased in February, forcing Abkhazia to impose 12-hour daily blackouts. Illegal cryptomining operations are a massive issue for Abkhazian energy exacerbating shortages, and although the fight against these acts is ongoing, they are proving insufficient. On top of all these, the Inguri hydropower plant suffered damage in March, limiting domestic production. By December 11, the entire country was without electricity as Russia withheld energy assistance. In addition to the chronic widespread unemployment Russia banned Abkhazian mandarin imports on December 6 in retaliation for the rejection of the Russian investments agreement, worsening economic difficulties by crippling one of the largest Abkhazian exports to Russia. Financial aid from Russia remained frozen throughout 2024, raising fears that state employees would not receive wages. Among the mostly negative developments were also positive ones, as Abkhaz language was added to Google Translate in June, and it was reported that an estimated 1.4 million Russian tourists visited Abkhazia in 2024, a vital boon for a tourism-reliant economy.

Republic of South Ossetia – the State of Alania

The year starts with significant economic challenges for South Ossetia. On January 10, amendments to the trade agreement with Russia take effect, abolishing customs duties on imported oil products and gas. However, Rosneft gains exclusive rights to supply fuel to South Ossetia, leading to a 7-10-day fuel shortage during the transition. Concurrently, South Ossetia introduces new VAT collection rules, which create confusion and effectively negate expected cost reductions from the trade agreement. Businessmen express frustration over paying the VAT in both Russia and South Ossetia, high customs brokerage fees, and inconsistent VAT application. Significant delays in processing cargo shipments at the Nizhny Zaramag checkpoint, particularly affecting food imports, exacerbate the situation. Some locals attribute these issues to the incompetence of the head of South Ossetia’s customs committee, others criticize president Alan Gagloev for failing to address the problems effectively. A conspiracy theory suggests that Georgian lobbyists in Tskhinvali and Moscow are orchestrating these difficulties to push South Ossetian businesses towards cooperation with Georgian enterprises and away from the Russian market.

The political landscape is dominated by the June 9 parliamentary elections, which also serve as an unofficial start to the 2027 presidential race. Gagloev faces significant issues: rising fuel prices, customs disputes, and cuts to state and civil service positions fuel discontent, while the administrations achievements are seen as being limited to small-scale projects. During the election campaign, party platforms align on most policy issues, except for the potential opening of a road between Russia and Georgia through South Ossetia. Most candidates oppose this idea on security grounds, while one suggests it could boost economic development.

The June 9 parliamentary elections themselves are marred by controversy. Five political groups are barred from participating, leaving seven parties and 112 candidates to compete for the 34 parliamentary seats under a mixed system where 17 seats are elected in single-member constituencies, and 17 seats assigned through proportional vote. In addition to the local polling stations, stations are opened in Moscow and in Vladikavkaz. Despite previous discussions to lower the electoral threshold to 3%, it remains at 7%, making it difficult for smaller parties to enter the parliament. Approximately 22,000 people vote, but election fraud is uncovered in Vladikavkaz, where pens with disappearing ink are placed into voting booths, rendering over 730 ballots unreadable. The central election commission further fuels controversy by postponing the announcement of preliminary results, violating electoral laws. According to the official results, four parties enter the parliament. Thanks to more wins in the single-member constituencies, the ruling party Nykhas secures a parliamentary majority with 15 seats (30.6% of votes), while the oppositional United Ossetia gains eight seats despite winning the most votes (31.5%). The People’s Party secures five mandates, and the Communist Party two. Neither is expected to oppose Nykhas. Notably, only one woman gains a seat in the parliament. The contentious election process leads United Ossetia to demand investigation into the alleged fraud. The party initially refuses to participate in the new parliament until the results are reviewed. However, when the general prosecutor’s office opens a criminal case, it is Nykhas that is deemed the victim: according to the prosecution, the ruling party lost more votes in the Vladikavkaz polling station than United Ossetia, and was therefore more impacted by the fraud. After a four-month standoff, United Ossetia’s MP’s take their seats in late October, citing the need to protect their voters’ interests.

2024 brings complexity to South Ossetia’s relations with Russia and Georgia, shaping the region’s political and economic dynamics as rumours of a Georgia-Russia rapprochement circulate. In February, a columnist in the Echo of the Caucasus online magazine claims that South Ossetian authorities have been instructed by Russia to avoid political issues that might cause scandals and interfere with Georgian Dream’s chances in Georgia’s parliamentary elections in October. Topics to avoid include discussions on revising the border with Georgia or holding a referendum on joining Russia. These claims are tested when three South Ossetian parliament members are stripped of their Russian citizenship and denied entry into Russia with their South Ossetian passports as well. The deputies accuse the president of orchestrating the move after they proposed restoring South Ossetia’s border to its 1922 boundaries, which would slightly expand the territory in comparison to the current borders. According to the deputies this might be an opportunity for Gagloev to discredit competitors ahead of South Ossetia’s parliamentary elections. All government institutions avoid commenting on the issue for more than two weeks. When Gagloev finally addresses the situation, he blames the deputies for provoking tensions with Georgia and accuses the collective West of attempting to open a second front against Russia through Georgia or Abkhazia. Curiously, these remarks are later dismissed by South Ossetian foreign minister as highly unlikely.

While most South Ossetians view all interactions with Georgia negatively, some see opportunities. Early in the year, some Georgian and South Ossetian entrepreneurs and activists meet to discuss economic cooperation, focussing on opportunities for small and medium-sized enterprises in agriculture and tourism. Despite administrative and legislative hurdles, some cooperation continues with aid from the Peace Fund, set up in 2009 to implement joint Georgian-Abkhaz or Georgian-Ossetian projects. This cooperation is seen as a way to overcome the isolation of the two communities from each other. However, as described above in the context of election debates, when the possibility of reopening a transit road between Georgia and Russia through South Ossetia is voiced, most candidates view it as a security issue. Local population reacts negatively as well, fearing increased Georgian control over the region. When Georgian Dream’s founder Bidzina Ivanishvili suggests that Georgia would apologize to the Ossetian for starting the 2008 war, should Georgian Dream win the upcoming elections, responses in South Ossetia focus on the need for tangible actions from the Georgian government, rather than mere words, including recognition of South Ossetia’s independence. Georgia’s refusal to sign a non-aggression pact with Abkhazia and South Ossetia after the 2008 war, and its lack of cooperation in the Geneva International Discussions (GID), contribute to scepticism about Ivanishvili’s statement, which is seen as a campaign slogan. During the election period in Tbilisi, South Ossetia closes three crossing points with Georgia for the about 1000 Georgian citizens in South Ossetia, claiming security concerns.

Interactions with Russia are interpreted through the prism of Russia’s changing relationship with Georgia. In March, Moscow appoints a new curator for South Ossetia, placing Alexander Mishenkov as the deputy head of the Russian presidential administration’s department for interregional and cultural relations with foreign countries. Unlike his predecessor, Mishenkov has little prior experience with South Ossetia, leading to speculation among Ossetians as to which political power the curator might favour. Following South Ossetia’s parliamentary elections, both Gagloev as well as his opponent, previous president Anatoli Bibilov rush to Moscow. Gagloev worries that despite his part winning the elections, the legitimacy of the win is in question due to the election controversies, and he might be marked as a lame duck president in the eyes of Moscow. When it emerges that Sergei Shoigu, secretary of Russia’s security council, has recently visited South Ossetia but has not met with Gagloev, it is seen as proof that he has indeed lost the favour of Moscow. At the end of August, Gagloev states that South Ossetian authorities are considering joining the Russian-Belarussian Union State as one of the most promising options for future development, and are actively working on enhancing cooperation with Belarus. However, as Belarus seems uninterested in South Ossetia, the statement is not taken seriously by the wider public. Instead, some politicians believe that South Ossetia should simply join Russia for more benefits. In September, Russia’s funding freeze in Abkhazia raises serious concerns that the same fate might wait South Ossetia. Putin’s failure to congratulate South Ossetia on the anniversary of its recognition and the unimplemented Moscow-Tskhinvali agreements from 2015 add to these concerns. It is then seen as a positive sign when Putin submits the military-technical cooperation agreement with South Ossetia, signed in August 2023, for ratification in the state duma. The agreement foresees strengthening the defence capabilities of Russia and South Ossetia, developing further a similar cooperation agreement from 2009. Critics however question the utility of such an agreement, and why the exact text of it remains unpublished. Furthermore, Russia expresses readiness to assist Tbilisi in its dialogue with Abkhazia and South Ossetia “as states”. At the GID meeting in November, Russia is more specific in terms of what are some of the steps Georgia should take to initiate dialogue, including initiating a process of border delimitation and subsequent demarcation, and offering legal guarantees on the non-use of force against Abkhazia and South Ossetia. The year ends on a serious note: the state cancels traditional public New Year’s Eve festivities, including a concert and a fireworks show, citing the need to spend funds on supporting the fighters in Russia’s war against Ukraine, and to give citizens the “opportunity to rethink their realities”.

The Republic of China (Taiwan)

2024 starts with a pivotal moment for Taiwan: the presidential and parliamentary elections on January 13. President Tsai Ing-wen from the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has reached the two-term limit, and the race to succeed her is tight. In polls, Tsai’s vice president Lai Ching-te leads narrowly over Kuomintang’s (KMT) Hou Yu-in and the Taiwan People’s Party’s (TPP) Ko Wen-je. The election draws global attention due to rising tensions in the Taiwan Strait. The outcome is anticipated to set the tone for Taiwan’s future relations with both China and the United States. While international observers focus on the geopolitical implications, domestic voters are primarily concerned with economic issues.

Despite China’s attempts to sway votes towards the KMT – seen as more amenable to China – Lai Ching-te wins with 40.1% of the vote, securing a historic third term for the DPP. Lai’s victory is seen as a mandate to continue promoting Taiwanese sovereignty and fostering a distinct national identity separate from China. However, the DPP loses its parliamentary majority, complicating Lai’s upcoming term as the opposition KMT and TPP hold a combined 60 seats out of 113. Parliamentary tensions escalate just days before Lai’s inauguration on May 20 when a fight breaks out in the parliament over an opposition-backed bill expanding parliament’s oversight. The DPP argues that the bill bypasses customary consultation processes and duplicates the control yuan’s role of investigating government officials and ordering impeachments. Public protests erupt, with an estimated 50,000 to 100,000 people making these the largest protests since the 2014 Sunflower Movement, but the bill passes 58 to 45. The KMT then announces a task force to investigate alleged DPP corruption. However, these parliamentary dynamics are disrupted in September, as TPP head Ko Wen-je is arrested on corruption charges, accused of accepting bribes during his tenure as Taipei mayor. Several other TPP members are charged with misappropriating political donations. This damages TPP’s reputation among the electorate for whom they’ve represented a welcome “middle way” alternative to DDP and KMT.

Image: Lai Ching-te, Hou Yu-in and Ko Wen-je (Source: NHK World)

Amidst the domestic political turmoil, China continues to exert pressure on Taiwan through military and non-military means. Just days after the election, China conducts joint combat patrols around Taiwan, marking the largest incursion since November 2023. In April, Chinese warplanes conduct sorties over the Taiwan Strait, coinciding with the end of US secretary of state’s visit to Beijing, during which China’s president Xi Jinping expresses his discontent with the US aid funding for Taiwan. On May 23, a few days after Lai’s inauguration on May 20, China launches a two-day military exercise. Codenamed Joint Sword-2024A – suggesting that the rest of the alphabet may follow –, the drills include mock air strikes with live missiles. Still, they are estimated to be smaller in scale compared to previous years. Taiwan’s national day celebration on October 10 brings the next large drills, codenamed Joint Sword-2024B. Starting without prior notice before dawn on October 14, the drills involve an unprecedented number of aircraft and vessels, with 153 aircraft – of which 111 cross the median line in a single-day record –, 14 navy ships, and 17 coast guard vessels participating. Notably, the vessels feature encircling the entire island and entering restricted waters around Taiwan’s outer islands. The drills are accompanied by a surge in cyberattacks, further highlighting China’s ability to disrupt Taiwan’s airspace and communications. In addition to military exercises, China intensifies its non-military actions to deter and weaken Taiwan. The Chinese coast guard becomes increasingly assertive, ignoring the long-standing “prohibited waters line” and ramping up incursions near Kinmen island – officially Taiwanese territory, but located just a few kilometres from the Chinese mainland. In February, the Chinese coast guard boards a Taiwanese tourist boat near Kinmen, triggering panic among the passengers; in July the coast guard steers a Taiwanese fishing boat accused of illegal fishing to port in mainland China.

As Lai Ching-te is known for his advocacy of Taiwanese independence, he is labelled a dangerous separatist by China, whose president Xi Jinping maintains that “the motherland will surely be reunited”. In response to Lai’s calls for dialogue and respect for Taiwan’s choices in his inauguration speech, China not only organises military drills, but also threatens to impose the death penalty on “extreme cases” of Taiwan independence advocacy. In August, China launches webpages listing Taiwanese officials deemed “diehard separatists”, encouraging the public to denounce them and provide information about their “criminal” activities. In a September interview, Lai claims that China’s insistence on pursuing territorial integrity is hollow because they are not pursuing the restoration of land lost to Russia during the same period that China lost control of Taiwan. Instead, Chinese ambitions are purely geopolitical. In a speech a few days before Taiwan’s national day in October, Lai argues that because Taiwan, or rather the Republic of China, has older political roots, the People’s Republic of China cannot become the motherland of the Republic of China’s people.

Lai also faces international challenges as China seeks to influence Taiwan’s foreign interactions. Two days after the January 13 election, Nauru announces it is switching recognition from Taiwan to China, reducing Taiwan’s diplomatic allies to just 12. However, fears of further derecognitions do not materialize, and in December, Paraguay declares a Chinese envoy persona non grata for pressuring the government to sever ties with Taiwan. China attempts to expand its influence to international forums as well: China claims “interference with its internal affairs” when foreign leaders congratulate Lai on his victory and on a successful and democratic election. When Taiwan hosts the annual summit of the Inter-parliamentary alliance on China (IPAC), a forum bringing together about 50 parliamentarians from 23 countries to discuss countering China’s widening international influence, participants report pressure from China to prevent their attendance. At the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF) summit, China, a “dialogue partner” rather than a full member, successfully pressures the forum to remove references to Taiwan from its communique. In October, the UK foreign office requests the postponement of former Taiwanese president Tsai’s visit to the parliament to avoid angering China ahead of new foreign secretary David Lammy’s upcoming “goodwill visit” to Beijing.

The US-Taiwan relationship remains pragmatic. In April, the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) announces plans to establish its third facility in Arizona, producing TSMC’s most advanced chips, following a multibillion-dollar subsidy pledge from the US government. The same month, the US Senate approves an $8.1 billion aid package for Taiwan as part of a larger $95 billion aid plan for Ukraine, Israel, and Taiwan. Additionally, Taiwan signs contracts with the US for advanced military equipment, including F-16 fighter jets, M1 Abrams tanks, and HIMARS rocket systems. China warns the US to cease arming Taiwan, asserting that such actions violate US commitments to China and embolden the “separatist forces”. In October, the US approves a potential $2bn arms sale to Taiwan, including advanced air defence missile systems. Once again, China strongly condemns the sale. Lai’s state visit to the Marshall Islands, Tuvalu, and Palau in December includes stopovers in Hawaii and Guam. These stopovers, formally labelled as such due to a lack of formal diplomatic ties, allow Lai to engage with supportive US politicians, and are a typical part of Taiwanese leaders’ travels to far-flung allies in the Pacific, Latin America or the Caribbean.

Indicating potential trouble ahead, Taiwan’s situation is complicated by US presidential candidate Donald Trump’s suggestion that Taiwan should pay the US for protection from China. In response, Taiwan emphasises the strong relations between Taiwan and the US, noting efforts to enhance its self-defence capabilities. Additionally, Elon Musk’s SpaceX requests Taiwanese suppliers to relocate their manufacturing operations due to “geopolitical concerns”, prompting some companies to change locations. Considering these developments, Taiwan announces it will have access to low earth orbit satellite internet services by end of October, provided by the UK-European company Eutelsat OneWeb, rather than Musk’s Starlink. The service is considered crucial in case a Chinese attack cripples the island’s communications.

Pridnestrovian Moldovan Republic (Transnistria)

Despite president of Transnistria Vadim Krasnoselsky hoping that all hardships will remain in the past in his New Year’s address, the year starts off with a cold shower to the de facto state. From January, Moldova introduces import and export duties for Transnistrian businesses. Transnistrian officials say that Moldovan side failed to inform them about the implementation of such duties in due course, catching Transnistrians by total surprise. In a televised address on January 5, Krasnoselsky accuses the Moldovan authorities in violating fundamental rights and crushing business, appealing to them to reconsider. He makes further appeals to the international community, most notably calling for the participants of the currently defunct 5+2 negotiation format and the OSCE to react to Moldova’s economic pressure. According to preliminary estimates, Transnistria would lose more that $5 million a year due to the new duties. Despite addressing the issue during the year’s first working meeting of political representatives in the negotiation process on January 16, Moldova refuses to scrap the duties. Transnistria retaliates by announcing trade duties for Moldovan farmers owning agricultural land and warehouses in the Dubasari district along the Tiraspol-Camenca route, to be paid when passing Tiraspol’s checkpoints. On January 24, Transnistrians are invited to protest Moldova’s policies. Transnistrian media reports about 50,000 participants, whereas published photos would indicate smaller participation.

During his annual address on January 22, Transnistria’s president dedicates the year 2024 to family and family values, and sets achieving political stability, economic self-sufficiency, and social justice as the goals for the de facto republic. But Transnistria needs support to achieve these aims. On February 3, Transnistria announces that more Russian gas is needed to continue operating its industry during the winter. And on February 28, Transnistria holds a rare “Congress of the Transnistrian People’s Deputies at all levels” (last convened in 2006) to discuss the political, economic, and security situation of Transnistria, as about a week before, Russia’s Defence Ministry had circulated claims that Ukraine was planning an armed incursion into Transnistria. Despite earlier speculation that Transnistria might ask for unification with Russia or announce another referendum on the issue, the congress of deputies simply appeals to Moscow for “protection” and for economic help. They also extend a plea to the UN, the OSCE, and to the EU to renew negotiations on solving the conflict. The plea is made a day before Putin’s annual address to Russian lawmakers, but Transnistrians’ hope that Putin would express his support to the region during it remains unfulfilled.

Image: “Congress of the Transnistrian People’s Deputies at all levels” in Tiraspol appealing to Moscow for “protection” and for economic help on February 28, 2024 (Source: CNN News/AFP/Getty Images)

Russia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs does respond, promising to carefully consider this request by Russia’s “compatriots”. Transnistrians’ security fears are heightened by reports in March that a kamikaze drone from Ukraine has destroyed a Russian military helicopter stationed near Tiraspol, followed by another claim in April that a drone hit a radar station that suffered minor damage. Moldova dismisses these claims as attempts to provoke fear and panic among the local population, while Kyiv blames Russia for arranging the provocation. But Russia does continue to offer “humanitarian help” to Transnistria by funding supplementary pension payments: Transnistrian press reports in May that after receiving the funds, pensioneers will receive 750 Rubles, i.e. 150 Rubles per month – as backpay for the first five months of the year, and another 150 Rubles in June. The next transfer of funds occurs in December.

Through the year, Transnistria raises the question of reviving the conflict resolution process, either in the 5+2 format, which according to Transnistria is frozen because of Moldova, or in a 1+1 format, but in the form of dialogue between senior officials of Moldova and Transnistria, as the current level and intensity of contacts is insufficient. In April, the OSCE chairman meets both sides, and reportedly, both Transnistria and Moldova agree that OSCE could play a prominent role in mediating a settlement. The OSCE organises the second working meeting of political representatives in the negotiation process in May, where all sides reiterate their continued commitment to achieving a peaceful settlement.

While Transnistria itself is not holding any elections this year, they are impacted by two elections. In February, Moldova rejects Russia’s request to open polling stations in Transnistria during their March 17 presidential elections for the estimated 220,000 Russian citizens in Transnistria. Russia ultimately ignores Moldova’s refusal, opening six polling stations in Transnistria, although the number is significantly lower than the 24 stations opened during the previous presidential election in 2018. Incidentally, the number of people voting in Transnistria remains at about 46,000 people – just about 20% of Russian passport holders – marking the lowest turnout of the past four Russian elections. In October, Moldova holds its presidential election and referendum on joining the EU. Transnistrian authorities pledge not to interfere with voter access to polling stations, but do object Chisinau’s decision to not open any polling stations in Transnistria itself. Instead, 30 polling stations are reserved in Moldova proper just for voters from Transnistria.

For Transnistrians, 2024 ends in tense anticipation: from January 1, 2025, a gas transit agreement between Ukraine and Russia is set to expire, threatening Transnistria’s economic lifeline. Alternative routes of supply are available, and the government is initially trying to retain calm by stating that it is not sure that gas deliveries will be cut. Still, preparations for such event begin in mid-December, when an energy emergency is declared for 30 days. During the rest of the month, Transnistria holds several security council meetings, and makes plans for handling the reduction of gas supplies. Although Moldova tries to negotiate with Russia on behalf of Transnistria on the continuation of gas supplies through the alternative routes, Gazprom announces on December 28 that it will cease deliveries at the end of 2024. On a final note, in September, Krasnoselsky presents a new legislative initiative whereby the term Transnistria will be equated with the concepts of Nazism and fascism, as it is a Romanian term. Instead, he advocates for the use of the name Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic. The parliament adopts this initiative unanimously.

Republic of Kosovo

As of January 1, 2024, the positive atmosphere created by the announcement that vehicles with Kosovo license plates would be allowed to enter Serbia, ending years of disagreement on this issue, begins to change. In 2023, Serbs in northern Kosovo, which was heading toward early local elections, petitioned for the dismissal of Albanian mayors in four municipalities where Serbs hold a majority, demanding new elections. Albanian mayor Lulzim Hetemi, who was appointed in late May 2023, took office amid great tension. His inauguration occurred under heavy police escort, and he faced protests from many local Serbs. If the petition gains sufficient citizen support, Hetemi, the mayor of Leposavic in northern Kosovo, has stated that he will not seek re-election in the upcoming mayoral elections.

In early February, German Defence Minister Boris Pistorius called for de-escalation in the region and announced that Germany would more than double the number of troops it was sending to the NATO peacekeeping mission. Pistorius affirmed that the Kosovo government could rely on the German military to promote stability in the region amid rising tensions with neighbouring Serbia. US and EU officials also accused Kosovo authorities of “unnecessarily escalating ethnic tensions” by banning the use of the Serbian dinar and ordering the Serbian minority to switch to the euro.

In April 2024, Kosovo began its first nationwide census in more than a decade, which included a survey of the ethnic Serb minority in the north. This was the second census since Kosovo’s independence from Serbia in 2008, and it started on April 5, running until May 17, 2024. However, Serbs boycotted the census. Parties representing Kosovo Serbs called for the boycott, arguing that participation would only confirm the “shameful success of the government of Prime Minister Albin Kurti in expelling Serbs”.

In May, German Ambassador to Pristina Jorn Rohde stated that Kosovo’s membership in the Council of Europe would require concrete steps towards the creation of the Union of Serb Majority Municipalities, which would represent Serb interests in four municipalities in northern Kosovo. He expressed hope that Prime Minister Kurti would change his stance before the ministerial committee meeting of the Council of Europe member states, expected on May 16 or 17. Toward the end of May, in line with an order by the Central Bank of Kosovo banning cash transactions in any currency other than the euro, Serbia’s Post Savings Bank closed six offices in four Serb-majority municipalities in northern Kosovo, while police took action. The United States and the European Union criticized the move, stating that it undermined Kosovo’s determination to resolve its relations with Serbia through EU-brokered talks.

On May 29, 2023, the first anniversary of violent protests in which 93 KFOR soldiers were injured in clashes with ethnic Serbs outside the town hall in Zvecan, the KFOR mission called for the perpetrators to be brought to justice. In late May, the Kosovo government, led by Prime Minister Albin Kurti, made the final decision to expropriate property in the Serb-majority municipalities of Leposavic and Zubin Potok in northern Kosovo, claiming approval from Kosovo courts. This decision was condemned by the embassies of France, Germany, Italy, the UK, the US, the EU, and the OSCE.

In mid-July, the Kosovo war crimes court sentenced former KLA member Pjeter Shala to 18 years in prison, ruling that he had committed war crimes against Serbian troops during the 1998-1999 Kosovo conflict. In August, following a decision by the Central Bank of Kosovo to discontinue the use of Serbia’s dinar, Kosovo Police conducted an operation to close nine offices operated by Serbia’s Post Savings Bank. Tensions escalated in early September when Kosovo Serbs protested against the Kosovo government’s decision to reopen the main bridge separating the Serb-majority north of Mitrovica from the Albanian-majority south. The reopening sparked a new row between the government and its Western allies, who sought to address the issue within the framework of the EU-brokered Belgrade-Pristina dialogue, rather than through unilateral actions by Kurti’s government. Kosovo then closed two of its four border crossings with Serbia following the protests. Kosovo’s Interior Ministry blamed the closure on “masked extremists” blocking traffic into Serbia. The border blockade followed police raids and the closure of five Belgrade government administrative offices in northern Kosovo.

In September 2023, a trial was held in the village of Banjska in northern Kosovo related to a deadly attack on police officers by an armed Serbian group. Kosovo Serbs arrested in connection with the attack were found not guilty. In November, Kosovo investigated a suspected terrorist attack on a water canal that caused significant damage to essential infrastructure. The US and EU condemned the blast, calling for the perpetrators to be held accountable. Kosovo authorities blamed Serbia for the attack.

In mid-November, the lead negotiators in the Kosovo-Serbia dialogue, Besnik Bislimi and Petar Petkovic, agreed to implement the 2023 Declaration on Missing Persons at a meeting in Brussels mediated by EU special envoy Miroslav Lajcak. In late November, an explosion near the town of Zubin Potok in an ethnic Serb-majority area of northern Kosovo damaged a canal supplying water to hundreds of thousands of people and the cooling systems of two coal-fired power plants that generate most of Kosovo’s electricity. As tensions with Serbia escalated, Pristina described the incident as an “act of terrorism” by the neighbouring country and mobilized its armed forces to prevent further attacks. Police arrested eight individuals in connection with the explosion. Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić rejected as Kosovo’s claims as “baseless accusations.”

Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus

In January, the UN Secretary-General’s Special Representative for Cyprus, Colin Stewart discussed with both President Christodoulides and Turkish Cypriot leader Ersin Tatar some of the issues that threatened the integrity of the buffer zone and disrupted the military status quo: “We hope for a positive 2024, as you know, 2024 marks the 60thanniversary of the UN presence in Cyprus. This is a very sad anniversary. We believe the Cyprus problem should have been resolved long ago,” he said. At the same time, the Turkish Vice President Cevdet Yılmaz, who inaugurated the Dr. Suat Günsel Mosque, the largest new mosque on the Near East University campus, stated that there are two separate states in Cyprus and no need to continue trying things that have been attempted many times before. “Anything discussed from now on should be discussed and negotiated between these two states. If you are looking for a solution, this is the solution,” he asserted.

Yet, the year 2024 represented also 50th anniversary of the Turkish military presence and 20th anniversary of failed Annan Peace Plan referendum in Cyprus. The unresolved Cyprus problem continues to deeply affect both economic and daily life in the TRNC. A new bill restricting northern taxi drivers from operating in the south has been submitted to the Cyprus parliament by the Transport Ministry. The bill will reduce the burden of proof on the state to convict those illegally providing taxi services, and it will also apply to taxi drivers registered in the north who are currently operating in the Republic. Transport Minister Alexis Vafeades explained that the new system would be “evidence based.” For example, “One can reasonably assume that someone who arrives at Larnaca airport three times in one day and picks up people all three times is a taxi driver. If they are detected by the police and do not have the necessary license, they can be fined”. In response to the planned restriction on Turkish Cypriot taxis operating in the Republic, Turkish Cypriot leader Ersin Tatar met with taxi drivers. “We will take the necessary measures within the framework of the principles of reciprocity according to the steps to be taken by the Greek Cypriot administration,” the TRNC Transport Ministry said in response to the move.

Although negotiations remain stalled, some progress appears to be underway for Turkish Cypriots. The Republic of Cyprus has begun processing citizenship applications from Turkish Cypriots in mixed marriages, where one parent is a citizen of Türkiye. Previously, applications were blocked under the 1974 Council of Ministers decision if the parents were married in the north after July 20, 1974. However, the government has now announced that it will review previously rejected applications. Additionally, it was confirmed that future applications from Turkish Cypriots in mixed marriages will also be processed. However, the government clarified that, according to official statements from the Republic of Cyprus, the cabinet has specified that the citizenship application system currently applies only to individuals who applied before 2007, have all necessary documents in order, and possess an application number confirming receipt. They also stated that new applications are not being accepted until further notice from the Republic of Cyprus.

Furthermore, Northern Cyprus, which remains under economic embargo, also grapples with political and economic challenges. Turkish Cypriot leader Ersin Tatar has asserted the TRNC’s rights over Cyprus’ 462,000-square-kilometer exclusive economic zone (EEZ), encompassing the continental shelf, territorial waters, and maritime jurisdiction areas. Speaking at an energy summit in the north, Tatar emphasized the need for cooperation between both sides on energy matters, particularly advocating for a connection to Europe via Turkey. “It is not logical or practical for the Greek Cypriot side to reject energy transfer to Europe via Turkey,” Tatar said. “The parameters of the game in the Eastern Mediterranean have now changed, and the formula for a fair distribution of energy potential is a two-state solution [for Cyprus].” He argued that maritime and international law “form the basis for the TRNC’s share of the Eastern Mediterranean’s energy reserves”.

The year 2024 is also notable for the TRNC’s unanimous parliamentary decision to transfer the operation of Geçitkale (Lefkoniko) Airport to the Turkish military. Meanwhile, prime minister Ünal Üstel secured a “historic” 16 billion Turkish Lira “Financial and Economic Cooperation Agreement” from Türkiye, and Turkish Cypriot butchers urged the northern government to intervene as consumers increasingly cross into the Republic of Cyprus to buy cheaper meat: “Our own citizens are now shopping in the south, pushing vendors to the brink of bankruptcy, unable to cover basic expenses like rent and utility bills,” they stated. Additionally, Turkish Cypriot leader Ersin Tatar made a historic visit to Australia, becoming the first serving TRNC president to travel Down Under. In an unprecedented move a group of 54 British politicians signed a joint letter to the then -UK Foreign Secretary Lord Cameron saying the government should allow direct flights between the TRNC and the UK, and Akan Kürşat was arrested in Rome on New Year’s Eve under a European arrest warrant issued by Italian authorities over his alleged involvement in the sale of Greek Cypriot properties in the north. Kürşat was later released after being brought to Cyprus and the case against him was dropped. Last but not least, attempts made by the Greek Cypriot leaders to join NATO were branded as “unacceptable” by the TRNC and Türkiye.

Authors:

Kristel Vits (Bougainville, Western Sahara, Somaliland, South Ossetia, Taiwan, Transnistria)

Özge Taşkın (Kosovo, Northern Cyprus)

Izzet Yalin Yüksel (Abkhazia)