Overview of 2022: De Facto States Under Increased Pressure

The De Facto States Research Unit looks back at the developments in the lesser recognised world in 2022. In last year’s blog, we noted the world becoming more unstable and unsafe for de facto states over 2021. The year 2022 has confirmed this trend with the escalation of Russia’s aggression in Ukraine to a full-scale war that has been an outright challenge to the post-World War II international order. Having previously benefitted from the “frozenness” of the international system – buying themselves time to focus on state-building and creating space for themselves by manoeuvring between different actors –, de facto states are now facing narrowing of options. While the continuing international power realignment might benefit some actors in short term and foment new secessionist movements, the increasing erosion of international order and reliance on power politics does not make the outlook for 2023 good for remaining de facto states.

The Republic of Abkhazia

Parliamentary elections in March result in a president-aligned parliament, raising fears that the body will lose its function of providing checks and balance on the executive. Several long-standing issues recur over the year: COVID-19 pandemic straining the fragile health sector; energy crisis creating hours-long blackouts during autumn and winter periods; corruption, including possible diversion of state funds through the renovation of the power grid; fuel shortage during the summer, mainly blamed on the record-high numbers of Russian tourists travelling in by their own cars, or by passenger trains which are given priority on the railway over supply trains. Relations with Georgia remain cold, with the current government rejecting any attempts of dialogue as benefitting Georgia. Moreover, a Russian-style law on foreign agents, targeting international organizations and local NGOs working with them, is being discussed. Many fear that such a policy, if adopted, will increase Abkhazia’s self-isolation. Russia-Abkhazia relations reach an unprecedented strain in 2022. In July, Abkhazians learn that president Aslan Bzhaniya agreed in January to transfer the territory of the Pitsunda state dacha to Russia – on loan to Russian state since 1995, supposedly Putin himself has now asked for this property. The agreement needs parliamentary ratification, and with a pro-president majority, the opposition fears it’s a done deal. The public rallies in protest, especially once it emerges that the territory agreed on is much larger than the actual property, leading the Russian ambassador to Abkhazia to threaten that if the territory is not transferred, Russia might reconsider its military base and investments in Abkhazia. Bzhaniya echoes the statement, saying that Abkhazia simply cannot afford to disagree. Towards the end of the year, increased border checks of both Abkhaz people and goods by Russians at the Psou border crossing, Russia’s refusal to supply additional electricity, as well as the decrease of support for the 2023 Abkhaz state budget, are all seen as ways of pressuring Abkhazia on the matter, although the agreement remains unratified by the end of the year. Government’s plans to solve the energy crisis through privatization – essentially giving a green light for Russian companies – along with the Pitsunda estate controversy and the planned law on foreign agents, lead in November to the formulation of a new protest movement, the Assembly of Socio-Political Forces, mostly comprised of young politicians and social activists united by concern over Abkhazia’s sovereignty. Not all is grim between Abkhazia and Russia, though: in September, a new agreement on dual citizenship is signed, giving more Abkhazians opportunities to travel (although EU bans Russian passports issued in Abkhazia and South Ossetia, distinguishable by serial numbers), and to receive Russian social benefits (considerably higher than Abkhazian ones). Abkhaz leadership plays with the idea of joining the Russian-Belarussian Union State once the war in Ukraine is over, and relations with Belarus seem to pick up over the year, evidenced by a high-profile visit from Belarussian president Aleksandr Lukashenka in September, followed by a visit from the delegation of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Union of Belarus and Russia in November. Despite deepening ties, recognition by Belarus is yet to come.

The Autonomous Region of Bougainville

Bougainville’s quest for independence continues. In April, Bougainville and Papua New Guinea sign the Era Kone Covenant, considered an important roadmap on future developments: it outlines how the results of the 2019 Bougainville independence referendum will be tabled and ratified in the National Parliament of PNG, which Bougainville’s president Ishmael Toroama says will happen in 2023. The Covenant also foresees that Bougainville’s independence should be settled not before 2025, and no later than 2027. In February, Toroama convenes the Constitutional Planning Commission, in May, he launches the Bougainville Constitutional Planning Commission Awareness and Consultations in North, Central, and South Bougainville, aimed at developing the new constitution through widespread consultations. But towards the end of the year, fears of PNG deadlocking the independence process start to grow, and in November, Bougainville threatens to cancel the upcoming meeting of the Joint Supervisory Body with the PNG government. Indeed, some statements from PNG prime minister James Marape reveal that he considers the Era Kone Covenant deadlines to be for reaching a settlement, which may or may not be full independence. He continues to campaign for Bougainville to settle for greater economic independence. Central Government’s concerns regarding Bougainville’s economic viability are not entirely unfounded, as about 85% of the region’s budget comes from PNG. Bougainville itself hopes that the agreement on reopening the Panguna mine which the local landowners reach in February, is an important step towards future economic growth that could sustain statehood, but concerns, notably over environmental impact and possible investors, remain. In December, an independent environmental and human rights legacy impact assessment of the Panguna mine begins – the work is funded by the previous operator Rio Tinto who had to abandon the mine at the civil war in 1989, following commitments announced in 2021.

Donbas (Donetsk People’s Republic and Luhansk People’s Republic)

On February 15, Russian State Duma appeals to the president for recognition of both DPR and LPR, aggravating tensions in and around Ukraine. On February 18, leaders of both statelets announce evacuation of civilians to Russia due to the increased threat of attack from Ukraine. Evacuations start a day later, when DPR and LPR leaders also announce general mobilization, men aged 18-55 are forbidden to leave. On February 21, Russia officially recognises DPR and LPR, a decision ‘celebrated’ by Abkhazia, South Ossetia, and Nagorno-Karabakh (these entities were also recognised by North Korea on 13 July 2022, and Syria on 29 June 2022). Russian troops enter Donbas. Abkhazia, which unlike South Ossetia has so far refrained from recognition, recognises both on February 25. On February 24, Russia starts a full-scale attack against Ukraine, evoking among other justifications the need of “ensuring the security of Russia and our citizens, protecting the residents of Donbas from genocide”. Throughout the spring and summer, men mobilised from Donbas area – about 140,000 by mid-June – are fighting on the frontlines, casualty rates are high due to lack of training and equipment. Local protests against mobilization are quickly supressed. In widely condemned staged referendums in Luhansk, Donetsk, Kherson and Zaporizhzhia on September 23-27, more than 95% of voters apparently want to join Russia. Despite not having full control of any of the regions or even clear borders, Putin announces the annexation of these oblasts on September 30, thus putting an end to DPR and LPR as de facto states.

The Republic of Kosovo

The year is dominated by tensions between Kosovo Albanians and the ethnic Serbs. In attempts to bring majority Serb areas of Kosovo under government’s full control, a series of administrative orders are introduced over the summer, including for transitioning about 10,000 cars from using Serbian number plates to Kosovo ones, starting from August 1, and introducing an extra entry document for Serbian ID holders, as Serbia requires similar entry-exit documents from Kosovars. The plans are postponed after Serbs close two border crossings between Serbia and Kosovo in protest. Serbia and Kosovo reach a free movement agreement following talks in Brussels, both agreeing to forego the entry-exit document requirement. The ‘number plate issue’ is reintroduced a few months later, to be implemented from November 1. Once again, tensions mount. Many ethnic Serbs in Kosovar government, police and judicial branch walk out of their jobs, creating a security vacuum. Angered further over plans to hold snap local elections in the municipalities whose mayors participated in the walk-out on December 18, Serbs in protest block roads at border crossings with Serbia, organise explosions and shootings. The events prompt Serbia to put its troops on the highest alert level, accusing Kosovo of “terrorism against Serbs,” and requesting permission from KFOR for up to 1,000 Serbian military personnel to enter Kosovo. Kosovar authorities scrap the licence plate plan once again in an EU-mediated agreement with Serbia, and postpone the elections until 23 April 2023, while NATO’s KFOR peacekeeping force has increased presence and patrols in Serbian dominated areas. Following these concessions, Serbia promises roadblocks set up by ethnic Serbs in Kosovo to be dismantled, and Kosovo reopens the main border crossing on December 29. Both the EU as well as the US urge Kosovo to set up an association of majority Serb municipalities, per a 2013 Brussels agreement as a way to de-escalate tensions long-term. Kosovo rejects the plan, as it would create a Serbia-aligned mini-state within Kosovo. On December 15, Kosovo submits an application to join the European Union. The Kosovo Specialist Chambers in the Hague, established in 2017, reaches its first verdicts in 2022: former KLA unit commander Salih Mustafa is sentenced to 26 years in prison for war-time torture. Two members of the KLA War Veterans’ Organisation are also convicted at the start of the year for obstructing justice and leaking information. Kosovo also starts preparing the first national strategy for transitional justice, to address the unresolved legacy of the conflict.

Image: Knyaz Lazar overlooking the square in North Mitrovica decorated by the Serbian and Russian flags. Many cars are with Serbian number plates or without any (Source: Eiki Berg).

Nagorno-Karabakh (the Republic of Artsakh)

In the aftermath of the 2020 war, the situation in and around what has remained of Nagorno-Karabakh is increasingly dire, with a lot of volatility. The de facto state is effectively side-lined in the Armenian-Azerbaijan dialogue – increasingly dominated by Baku, and with the West slowly replacing Moscow in mediation – over the territory’s final status. By October, Armenian president admits that a peace treaty with Azerbaijan might not include NKR, making it a separate agenda. NKR authorities insist that any agreement that considers NKR as part of Azerbaijan is unacceptable, while Azerbaijan’s president calls for Armenians of Karabakh to accept that the conflict has ended, and that they are citizens of Azerbaijan that should either integrate or relocate. Intermittent clashes between Azeri and ethnic Armenian soldiers break out throughout the year, with Azerbaijan subjugating more areas under its direct control. The inability of Russian peacekeepers to maintain order and peace is periodically criticised by Artsakh, by Armenia, as well as by Azerbaijan. In March, the gas pipeline supplying NKR with Armenian gas is damaged, Azerbaijan refuses access for repairs for 10 days, leaving most of about 120,000 Armenians remaining in NKR without heat and power in the middle of the winter. In May, NKR authorities initiate a process of constitutional reform – transition from a presidential to a semi-presidential system is hoped to provide more flexibility in emergency situations, improving security of NKR. The timing of this step is criticised by local opposition. The switch to presidential system was made in 2017, when consolidation of power was seen as benefitting the security situation. In September, Ruben Vardanyan, a Russian billionaire of Armenian descent, renounces his Russian citizenship, to move to NKR. Amidst speculation that the move is somehow orchestrated by Moscow, he claims he has not done so for the sake of a position in NRK. In November, he is appointed prime minister. In December, Azerbaijani eco-activists block the Lachin corridor on grounds of Armenians continuing to operate polluting metal mines in areas still under NKR control, halting the movement of people as well as goods on what Armenians call the “Road of Life”, the only road that connects Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh as the construction of an alternative route bypassing Lachin area is not completed. The infrastructure supplying NKR with electricity, gas, telephone, and internet connections also runs through the Lachin corridor. With Artsakh’s gas supply being once again cut off, it creates a humanitarian catastrophe as food and medicines run out. People in NKR gather in mass protests. The road remains blocked by the end of 2022 and beyond, with the situation on the ground growing progressively worse, despite calls from the international community for Azerbaijan and Russian peacekeepers to ensure access.

Image: Azerbaijani eco-activists blocking the “Road of Life” (Source: IARI, 07/02/23)

The Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus

Northern Cyprus finds itself in economic crisis in early 2022. The freefall of lira has exposed the pitfalls of being overly dependent on the patron state both in terms of state budget, as well as trade, and Turkey’s increased interference in TRNC politics raises protest among federalists. Further protests are staged in March against the signing of an economic protocol between TRNC and Turkey which, opposition argues, is accompanied by laws curbing freedom of expression and civil society, while promoting Islam. In May, it emerges that the economic protocol, foreseeing a loan of around 240 million Euros for TRNC, has been signed on April 14 with the inclusion of the aforementioned limitations. In September, protests erupt over the start of construction on a Turkey-funded 155 million Euro government complex including a mosque, a palace, and a new parliament building that critics believe is another sign of annexation. The municipality itself tries to file a case in court against the construction, based on lack of necessary building permits, but their case is rejected. In December, Turkish Cypriot businessman Asil Nadir sells his Kibris media group, which includes the daily Kibris, the English-language Cyprus Today, a radio and a television station, to a Turkish firm allied to Turkey’s ruling party. Despite fearing closer ties with Turkey, president Ersin Tatar’s right-wing National Unity Party (UBP) that is in favour of increased cooperation emerges victorious, while taking 24 of the 50 seats, and forming a governing coalition with the Democratic party and Rebirth Party after snap parliamentary elections on January 23. In response to USA’s decision to lift an arms embargo in place since 1987 from the Republic of Cyprus from 2023, both Turkish president and foreign minister promise to reinforce their troops in Northern Cyprus, in protection of the local population. In December, this is followed by news that Turkey will build a naval base on the island. In early October, Turkish Cypriot foreign minister issues an ultimatum to the UN: recognise TRNC within a month, or leave the island. TRNC maintains that their consent should be sought for the renewal of the peacekeeping mission’s mandate, promising to evict them from their bases in the North, most notably from Karolou Stefani base north of Famagusta, otherwise. Russia announces plans for direct flights between Russia and Northern Cyprus, the only country outside of Turkey to do so. Initially, flights are supposed to start from November 15 – the anniversary of TRNC’s declaration of independence – but are later postponed to early 2023. According to Russian news outlets, about 10,000 Russians live in TRNC. Local elections take place on December 25 – this time, opposition manages to gain most mayoral positions, including in Famagusta, where Turkey’s meddling is seen as a reason why some candidates withdraw from the race. Despite long-term murmurs, no recognitions are achieved this year, although TRNC is admitted to the Organization of Turkic States as an observer. President of TRNC, Ersin Tatar, reaffirms through the year his commitment to a two-state solution, claiming that full recognition of TRNC cannot be prevented.

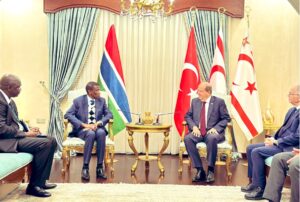

Image: Vice President of Gambia Badara Joof in an official visit to TRNC on November 30 (Source: www.kktcb.org)

The State of Palestine

2022 becomes the bloodiest year on record in the West Bank and Jerusalem area since the end of the second intifada in 2005 according to UN, with at least 170 Palestinians being killed in the West Bank and East Jerusalem area. The fighting initially picks up in March as Palestinian terrorist attacks against Israel increase in intensity. At the end of the month, the Israeli Defence Forces launch the months-long operation Breakwater, aimed against militants from al-Aqsa, Hamas, and Palestinian Islamic Jihad, but prompting the emergence of new armed groups in response, as well as the re-emergence of some old ones, especially around cities of Jenin and Nablus. The new groups do not align with specific Palestinian parties or movements. Al Jazeera journalist Shireen Abu Akleh is killed by the Israeli Defence Force in one of their offensives in May – according to evidence submitted by Al Jazeera to the International Criminal Court, the journalist was directly targeted by the IDF. IDF organises operation Breaking Dawn, a three-day bombing campaign in Gaza in August, killing at least 49, including 17 children. The raid ends with an Egyptian-mediated truce between Israel and militant group Palestinian Islamic Jihad, as Hamas has decided not to join the fighting. They also target human rights groups, raiding and closing offices in the West Bank. IDF increasingly resorts to tactics used in the 2000-2005 intifada, such as punishing sieges on neighbourhoods and cities, and targeted assassinations in the West Bank. In addition to IDF activities, attacks by Israeli settlers against Palestinians in the West Bank also increase in 2022, becoming more coordinated. At least three Palestinian are killed in these settler attacks. Complicating the picture is the lack of a clear, unifying Palestinian governance structure – the Palestinian Authority nominally in charge in the West Bank is losing support, being seen by many as colluding with Israel. Human Rights Watch claims that Palestinian authorities both in the West bank and the Gaza strip use systematic torture on detained critics, further undermining their standing within their own communities. In August, Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas draws international condemnation when, during a press conference with the German chancellor Olaf Scholz in Berlin accuses Israel of committing “50 Holocausts”. In Gaza, residents are able to enjoy swimming in the Mediterranean for the first time in years: as three internationally funded sewage treatment plants have been able to operate more steadily, sea pollution has dropped to levels safe enough for swimming on large parts of the coastline. Formed at the end of December, Israel’s new government, headed by Benyamin Netanyahu and being called the most far-right coalition ever, makes West Bank settlement expansion its priority, and seeks to change the status quo on Jerusalem’s holy Temple Mount, which so far has not allowed Jewish worship. In November, US president Biden names a new special representative for Palestinian affairs, considered a significant upgrade of relations. US officials continue to reaffirm their commitment to a two-state solution. On December 31, the UN General Assembly passes a resolution calling on the International Court of Justice to give an opinion on the legal consequences of Israel’s illegal occupation of Palestinian territories.

Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (Western Sahara)

Conflict between the Polisario Front and Morocco toils on, intensifying at the end of 2022. In March, Spain announces a major policy shift towards Western Sahara: abandoning neutrality, it is now endorsing Morocco’s plan for an autonomous Western Sahara region, in what is seen as an attempt to pacify Morocco following worsening of relations the year prior. Polisario Front reaffirms the right of the about 350,000 to 500,000 strong local population to hold a referendum on their future. Algeria, supportive of Polisario Front and home to about 176,000 Sahrawi, as well as a big gas supplier of Spain, reacts by recalling its ambassador to Spain, and by suspending a 20-year cooperation treaty. But Polisario Front is struggling, as Morocco is ramping up its military and its efforts. In August, the World Food Programme announces that due to rising costs, monthly food rations in the Sahrawi refugee camps in Algeria need to be cut by over 75%, less than half of the recommended daily intake of calories per person. In the Western Sahara area proper, Morocco continues with resettlement, its people outnumbering local Saharans three to one. Football World Cup reveals some complexities of identities on the ground: among Western Saharans celebrating Morocco’s win in December are some Sahrawi people, noting that despite discontent with the Moroccan state as such, joy over the success of the national team has united Arabs and Africans alike, that since cease-fire in 1991 have merged and coexisted in a common environment. But others remain steadfastly anti-Moroccan, the feeling extending to actively rooting against the football team. At the end of October, UN Security Council votes to extend the mandate of the UN Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO) until 31 October 2023. Peacekeepers are tasked with monitoring and reporting, and, where possible, with mine clearance. UN also called for a revival of UN-led negotiations on a mutually acceptable political solution for the region. Kenya reiterated recognition on September 16. Colombia and South Sudan resumed diplomatic relations on August 10 and September 20, respectively.

The Republic of Somaliland

From the start of the year, presidential elections, scheduled for November 13, raise concerns. Opposition fears that incumbent Muse Bihi Abdi seeks to forego the elections and extend his tenure. Clashes between security forces and people demanding the timely conduct of elections erupt in August, killing at least five people; dozens are arrested. International community condemns the excessive use of force, and calls for dialogue to set up a roadmap for elections. In September, the electoral body claims that due to technical and financial reasons, presidential elections can’t take place for about another nine months. On October 1, Guurti – the non-elected gathering of tribe elders that functions as the upper house of the parliament – extends Bihi’s term for another two years, and its own mandate by another five years. Opposition refuses to recognise Bihi’s presidency after November 13. Another important vote is set for December for deciding the three parties allowed to participate in formal politics (this system is in place to curb clan-based fragmentation and political deadlocks), the postponement of the presidential elections creates confusion and quarrel over the timeline and sequencing of elections. Drought continues to plague Somaliland, impacting over 800,000 people, and causing many to leave homes in search of food and water. Government provides humanitarian assistance, many states provide international aid as well. In April, a fire at the main market in capital city Hargeisa destroys hundreds of businesses, mostly run by women. About two dozen people are injured. The government estimates the economic impact of the fire to be about 60 percent of Somaliland’s GDP. Before domestic crises take over, Somaliland makes an active push for international engagement and recognition. In January, some members of UK’s House of Commons call for Somaliland’s recognition. Following large public rallies in support of independence and recognition, Somaliland’s government announces the suspension of talks with Somalia, citing lack of seriousness on latter’s part. In December, Bihi announces that the basis for the renewal of talks is a two-state solution, with an international mediation mechanism. Also in January, Ethiopia announces after a visit by Somaliland’s president an upgrade of their counsellor general in Somaliland to full ambassador – the first state ever to do so. In February, Somaliland’s foreign minister leads a delegation on a visit to Taiwan – the friendship is fruitful, as Taiwan pledges funds to combat drought, as well as provide relief after the Waheen Market fire. In March, president Bihi visits USA, meeting with government representatives, and with diaspora representatives. But just as Somaliland is starting to gain international support, protests calling for reunification with Somalia break out in the Sool region from December 28. As security forces respond with violence, protests quickly grow in scope and intensity.

Republic of South Ossetia – the State of Alania

Elections are on the agenda for South Ossetia – the first round of presidential elections are held on April 10, the second on May 8. Before elections, the incumbent president Anatoly Bibilov positions himself as Moscow’s darling. He supports the deployment of South Ossetians to fight in Ukraine as contractors of Russian military units in South Ossetia, promises a referendum on joining Russia, but also has the central elections commission disqualify some of his strongest contenders. Five candidates compete in the first round, Bibilov and Alan Gagloev, leader of Nykhas party, advance to the second round. In the end, Bibilov’s authoritarian tendencies, the belief that he had surrendered territory to Georgia, and backlash from South Ossetian soldiers deserting from Ukraine contribute to his downfall: Gagloev wins the second round in what many consider protest voting, as the opposition lacks a viable election programme. While still supportive of strong ties with Russia, Gagloev cancels the referendum, a step welcomed by Russia due to “unsuitable timing”. Gagloev assures that consultations with Russia regarding greater integration are still ongoing, but like his predecessor, leaves unanswered whether joining Russia means becoming an administrative part of Russia, or joining the Union State with Russia and Belarus (and possibly Abkhazia) as an equal. There is a slight thaw in the relations with Georgia in September, following Gagloev’s campaign promises to ease South Ossetia’s self-imposed isolation: after about three years of closure, some crossing points between South Ossetia and Georgia are temporarily reopened, albeit only for pedestrian traffic. South Ossetia also continues with borderization on the South Ossetian-Georgian boundary line, adding observation posts, fencing, and border signage. In December, the International Criminal Court in The Hague announces the conclusion of the investigation of war crimes and crimes against humanity during the 2008 Russian-Georgian war, earlier in the year, arrest warrants had been issued to three former South Ossetian officials. The actions of ICC are denounced in South Ossetia as being biased, pro-Georgian. During the second half of the year, the honeymoon period between South Ossetians and their new president comes to an end: as Gagloev refuses to resign as party leader despite his presidency, and installs his own party member as the new speaker of the parliament (thereby concentrating power), he is moving away from the democratic reforms he promised in the campaign.

The Republic of China (Taiwan)

Taiwan continues its strategy of strengthening relations with friendly nations, assisting them when Beijing retaliates by blocking or restricting imports. At the beginning of January, Taiwan’s state-run Tobacco and Liquor Corp buys 20,400 bottles of Lithuanian rum after China indicates the shipment will be blocked. Sharing cocktail and cooking recipes on social media, TTL sells out first batches of the rum in an hour from hitting stores. In October, Taiwan lifts the Covid-related entry restrictions for tourists, which have been in place for more than 2.5 years. The overall security situation around Taiwan grows progressively worse over 2022, China steps up its sabre-rattling with frequent air incursions into Taiwan’s defence zone throughout the year, and with military exercises around Taiwan. China’s 20th party congress in October is carefully followed: as Xi Jinping consolidates his power, he and the rest of the party make sure to reiteratethat Taiwan will be brought back into Chinese fold – by force, if necessary. US-Taiwan relations pick up: in February, USA approves a 100 million USD deal for upgrading Taiwan’s Patriot air defence system. Early March, a visit to Taiwan by a delegation of former US top security and defence officials, sent by president Biden, draws China’s ire. In May, Biden outright states that US would defend Taiwan militarily if attacked by China. In August, House speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan heightens tensions between USA, China and Taiwan, even people in Taiwan are splitover whether the visit is an extraordinary show of support, or a provocation. A US congressional delegation makes a further stand by visiting Taiwan shortly after Pelosi, as well as the announcement of bilateral trade talks. Local elections take place in November. Seen as a test of the ruling party’s support ahead of the next presidential election (in 2024), the governing Democratic Progressive Party’s (DPP) campaign focuses on threat from China over local issues – a strategy which does not bear fruit, as the party loses several races to the opposition, leading to president Tsai Ing-wen’s resignation as party leader. In response to sabre-rattling from China, Taiwan increases defence spending, plans to produce drones and more missiles, and to improve civilian defence capabilities. At the end of 2022, plans to extend compulsory military service from four to twelve months from 2024 are announced. But the military is facing an uphill struggle, as low reputation turns people towards civilian defence and resistance initiatives, instead. Despite this, many Taiwanese believe that a war is unlikely in the next decade, nor do they pay attention to China.

Image: Nancy Pelosi’s official visit to Taiwan on August 3 (Source: Taiwan’s Presidential Office)

Pridnestrovian Moldovan Republic (Transnistria)

Transnistria gains international attention in 2022 in relation to Russia’s war in Ukraine, both concerns that the breakaway territory could be used to launch another attack on Ukraine, that advancement in Ukraine could be used to form a land connection between Russia and Transnistria in further geopolitical plans, or that Transnistria could be used to escalate the conflict to another country, are aired. On March 15, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe votes to recognise Transnistria as a region occupied by Russia. Transnistria is inevitably impacted by the war: its elites are isolated as both Ukrainian and Moldovan authorities are staunchly anti-Russian. In a careful balancing act, they avoid officially endorsing the invasion of Ukraine, as many in Transnistria, including prominent figures, are ethnic Ukrainians, and many open their homes for Ukrainian refugees. The state itself opens 6 refugee centres by the beginning of March. Ukraine destroys much of the infrastructure connecting them at the start of the war and closes the border, increasing prices and trade reliance on Moldova, which temporarily halts export from the Moldova Steel Works Factory on grounds of environmental concerns, although the licence is then extended multiple times. This company contributes considerably to Transnistria’s state budget. From August, Moldova requires Transnistrian officials to notify them before work trips abroad that use the Chisinau airport, and blocks Russian troop rotations in Transnistria-based Operative Group of the Russian Troops that now also need to travel via Chisinau instead of Ukraine. About 1,700 soldiers are based in Transnistria, divided between Russian peacekeepers and the Operative Group, although they are de facto the same, of these, about 70 to 100 are Russian officers, the rest being locals employed by Russia. In response to Moldova’s EU accession application, Transnistrian authorities demand recognition as they had not been consulted on the plans. At the end of April, a series of attacks in Transnistria raise concern: first, Ministry of State Security headquarters are hit by portable anti-tank grenade launchers, followed by explosions at radio towers broadcasting in Russian, and shots fired around the Cobasna ammunition depot, and further attacks on a fuel depot and a conscription centre. Ukraine is accused of the attack by the authorities (and Russia), while Moldova claims infighting within Transnistria to be behind them. Among the Transnistrians, rumours of being mobilised by Russia raise further anxiety, prompting many to leave. Authorities declare a red-level terror alert, and announce new security measures, such as military checkpoints at the entrances of cities, and the cancellation of the 9 May victory day parade. At the end of May, a new prime minister is appointed by president Vadim Krasnoselsky, but the move is considered no more than a formality as the president holds full political power, and the prime minister is a technocrat close to Sheriff corporation. Towards the end of the year, Russian gas delivery cutbacks also affect Transnistria, although people blame Moldova for the shortage. Despite all difficulties throughout the year, Transnistria maintains that its goal of joining the Russian Federation remains unchanged.

Author: Kristel Vits