Bougainville: Difficult Road Ahead

Establishing an independent state is undoubtedly one of the most grueling and unpredictable political endeavors of our time. Setbacks can even occur when the finish line is in plain sight. Few know this better than the people of Bougainville, an Autonomous Region (AROB) within the state of Papua New Guinea (PNG). Although the Bougainvilleans overwhelmingly voted in favor of independence in an internationally supported status referendum in 2019, the road ahead is far from clear.

According to the 2001 peace agreement that paved the way for the plebiscite, AROB and PNG will have to negotiate the next steps. A political deadlock seems likely as both sides have diverging visions of Bougainville’s future status. In addition, the parliament in Port Moresby is supposed to have the final say on all agreements. The result is difficult to predict; however, a negative outcome is quite possible. Australia, the leading regional power, PNG’s patron, and the crucial external factor throughout the whole secessionist conflict, seems to have made a decision already. After a talk with PNG’s prime minister James Marape, Australia’s Defense Minister Richard Marles declared: “As a witness to the arrangements that were put in place in respect of Bougainville more than 20 years ago, our job is to support Papua New Guinea. And that’s what we’re going to do.”

Ishmael Toroama, AROB’s president, who is determined to see Bougainville independent by 2025, responded quickly and unequivocally: “What we are witnessing right now is simply history repeating itself where the Australian Government throws its support behind the Government of Papua New Guinea to destabilise yet again Bougainville’s right to self-determination.” Waning international support is only one of plenty of issues on the table of Bougainville’s government. With independence within arm’s length, Bougainville will have to overcome a series of complex challenges – some reaching back decades, others new – before its ultimate goal can be achieved.

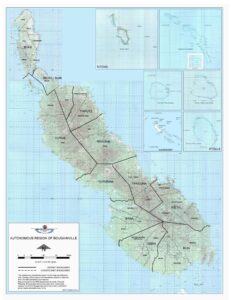

Image: Map of AROB (Source: Autonomous Bougainville Government)

The current negotiations are the final phase of a peace process that began in 1997 with the Burnham Truce and the Lincoln Agreement that both ended the violent confrontation between the secessionist Bougainville Revolutionary Army (BRA) and the Papua New Guinea Defense Forces (PNGDF). The conflict caused immense suffering among Bougainville’s population. Traumatic experiences are still very vivid in the memories of many Bougainvilleans. As a result of atrocities (by both sides), a sea blockade that caused a shortage in medication and health services, and the collapse of the economy, approximately 20,000 people died in the conflict – roughly 10% of the population. Entire settlements, including the former capital Arawa, were destroyed and subsequently abandoned. Bougainville island was cut off from the outside world. Only marginal humanitarian aid reached the conflict zone, as organizations such as Médecins Sans Frontières had to end their engagement due to safety concerns. The neighboring Solomon Islands became a safe haven for Bougainvillean refugees and a hub for the BRA – a situation that almost drew the country into the conflict. For some BRA members, the 1997 agreement was seen as a victory and a major step on the way to independence.

The truce paved the way for a more comprehensive settlement in 2001. Brokered by Australia and New Zealand, the Bougainville Peace Agreement (BPA) rests on three pillars:

- Disarmament of all militias and a weapons disposal

- Self-government and autonomy for Bougainville

- A status referendum after a significant transition phase

With the help of a multinational peacekeeping force, disarmament went smoothly. The PNGDF withdrew from the area. Bougainville was transformed into an Autonomous Region with significant self-rule competencies exercised by an Autonomous Bougainville Government (ABG) in conjunction with a Bougainville House of Representatives. A remarkable peacebuilding process was initiated, resting on traditional forms of dialogue and reconciliation.

The BPA’s final provision sought to address the status issue. Following a transitional phase, the population should express their preference for Bougainville’s political future in a referendum. The outcome, however, should not be immediately binding. Instead, the result was supposed to inform a negotiation process between the governments of AROB and PNG on the terms of a status change. PNG’s parliament then should have the final say on the outcome.

After 18 years of waiting, a series of last-minute postponements, and with supervision from the international community, the referendum finally took place in November and December 2019. The electorate could vote on whether they wanted Bougainville to “have (1) Greater Autonomy [or] (2) Independence.” Surpassing even the most optimistic expectations, a vast majority of 97.7% voted for independence (see Annie Rose Healion’s blogpost for a more detailed background to the conflict and the referendum). Despite this historic vote, the outcome is still open.

Image: Bougainville House of Representatives in Kubu, Buka (Source: Christopher Brucker)

Just as the government in Buka was getting ready to go to Port Moresby and negotiate the terms of Bougainville’s independence, the COVID-19 pandemic suddenly brought everything to a halt in March 2020. Travel between Bougainville and PNG proper was disbanded. A developing country with only a rudimentary public health sector, PNG struggled to fend off the pandemic. The vaccination campaign could only reach a small portion of the population, aggravated by fake news that caused widespread skepticism towards preventive health measures. As in other parts of the world, the pandemic led to an economic fallout in the region. Infrastructural development, widely regarded as a prerequisite to stimulate economic growth and ultimately achieve long-term viability for an independent Bougainville, intermittently came to a halt. Up until early 2022, only a few expatriates could reach AROB.

In September 2020, former BRA commander Ishmael Toroama was elected president of AROB. From the beginning, he made clear that he would accept the vote as a mandate to work toward Bougainville’s independence. Shortly after his inauguration, Toroama declared that he is aiming for independence by 2025, with 2027 as the latest possible fallback option should preparations take longer. Known in Bougainville as a determined secessionist and fierce politician, there is no doubt that Toroama will push hard to achieve this ambitious aim.

For PNG, the Bougainville conflict can be seen as one of the defining political issues in the country’s history. With approx. 800 native languages and a territory that involves high mountains, deep jungles, as well as ocean islands, PNG has an almost unparalleled degree of cultural and geographic diversity. The threat of secession and disintegration looms behind all crucial political shifts in the country. Until the outbreak of the war in 1989, revenues from mining in Bougainville were responsible for a considerable share of PNG’s national income. The violent conflict caused loss, trauma, and economic downfall also in PNG. The infamous Sandline affair, the conflict’s climax, brought the country to the brink of a military coup d’état. This illustrates why the current government in Port Moresby wants to retain control of Bougainville and insists on adhering strictly to the BPA to manage the peace process.

The post-referendum negotiations finally re-started in May 2021. As a significant first step, the governments of PNG and AROB in July agreed on a roadmap that foresees the continued transfer of political powers to Bougainville until 2023, mainly in the economic field. In addition, it was decided to reach a final status settlement “no earlier than 2025 and no later than 2027.” Throughout the negotiation process, the Marape government made clear that it would insist on the provision that the PNG National Parliament has the final decision-making power. Despite such pitfalls, the declaration meant a considerable achievement for AROB. The Toroama government announced its plan to accompany the political negotiation process with an Independence Readiness initiative that would focus on building fiscal sustainability through external economic assistance and investment.

The summer of 2022 saw parliamentary elections in PNG. In line with the 2021 roadmap, this very parliament will decide on the political status of Bougainville. On the eve of the 2022 elections, Toroama encouraged all Bougainvillean candidates to take the situation seriously and treat the vote as a mandate to fulfill the goal of independence. Much to the disdain of the AROB government, Marape announced holding PNG-wide consultations on Bougainville’s future status. Such measures are not foreseen by the BPA, Toroama replied. Relations between the governments in Buka and Port Moresby are cordial, however. Whether the foreseeable impasse in the negotiation process has the chance to change that, leading to a more confrontational dispute, is beyond my comprehension. A lasting stalemate or a negative parliament vote in PNG will surely lead to a new conflict phase.

Bougainvilleans are well aware of this danger. After 2019, expectations were widespread that the referendum results could be an asset in the negotiation process. The international legitimacy it had created would help bring about Bougainville’s independence, regardless of PNG’s eventual rejection. In the event of a governmental or parliamentary obstruction, the international community would step in and pressure PNG to accept Bougainville’s independence. Greater autonomy, the second option in the 2019 referendum and a possible compromise solution, seems off the table at the moment. In any case, it is hard to imagine that the government in Buka will accept a ‘No’ from the PNG parliament. Anthony Regan of the Australian National University even sees the chance of a unilateral declaration of independence in 2027.

Image: Poster from the PNG general elections in AROB (Source: Christopher Brucker)

In his inaugural speech, Toroama explicitly mentioned Bougainville’s international relations as a key pillar of his overall strategy. However, and this is a strictly personal observation, an international campaign can barely be seen. While the BRA had the support of grassroots activists in Australia and professional Human Rights advocates in Geneva, such contacts are largely idle now. As I was told in Arawa, the establishment of a Ministerial Committee on International Relations had to be postponed because the designated responsible is facing severe health problems. Only recently, the ABG has begun to intensify its external economic relations. Still, Bougainville now barely has a functioning foreign policy, let alone stable contacts with foreign governments that could potentially act as diplomatic brokers or advocates. In the face of rising international tensions, it is questionable whether the international community would unite and coerce PNG to let Bougainville go.

In the economic sphere, however, Bougainville indeed could attract a number of outside actors. The shut-down Panguna Mine in the center of the main island still holds one of the largest copper and gold deposits in the world. Earlier this year, debates about a re-opening have gained trajectory. Local landowners reached an agreement with the ABG that will allow re-starting mining activities in order to secure a possible “economic guarantor for Bougainville’s independence.” Where the necessary investments will come from and who is going to carry such an enormous undertaking out it is still an open question. A number of international mining corporations are currently seeking a license to re-open the mine and start operations. Some Bougainvillean politicians – among them prominent ex-BRA commanders – have openly contemplated cooperating with China on this issue, granting them mining rights in exchange for infrastructure investments.

The South Pacific is rapidly becoming an arena of the looming conflict between China and the West. Bougainville could easily be drawn into this confrontation. China is seeking to strengthen its regional military presence and has recently intensified its military cooperation with PNG as well as the neighboring Solomon Islands. Observers expect that an independent Bougainville could become a credible target of China’s appetite for a permanent foothold in the South Pacific. Which brings us back to the Australian Defense Minister. After Toroama’s outspoken reply, Marles’ ministry was busy downplaying the tone of the original statement, recalling that “Australia was a witness to the Bougainville peace agreement more than 20 years ago. And as such, we are completely committed to the processes contained within the Bougainville peace agreement.”

Graeme Dobell of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute sees Australia’s strategy as one of a careful “balancing” between Buka and Port Moresby, seeking to preserve the peace process. There is, however, reason to suggest that Australia prefers to avoid having a dysfunctional and, in the worst case, only partly recognized (de facto) state of Bougainville in its already troubled neighborhood. Canberra is certainly not an outspoken supporter of Bougainville’s independence and can hardly be expected to step in on the side of AROB should the PNG parliament vote be negative.

With the proposed independence date getting closer (again, this is a personal observation), ordinary people in AROB slowly start worrying about Bougainville’s future, especially when it comes to economic viability. Indeed, although growing, economic development is still marginal. The 2022 budget is about 473 million Kina – around 135 million Euro (GDP figures are not available). Bougainville’s infrastructure badly needs investment. AROB is structurally dependent on payments from Port Moresby. Only roughly 16% of the budget can be raised internally through taxes, concessions, concession rights, fishing licenses, etc.

In parts of Southern Bougainville, security remains a concern. The Buin area lately saw attacks by ex-BRA fighters operating under the name Mekamui, who keep resisting the post-2001 disarmament process. Even more profound issues, such as climate change, drought, and sea level rise, already threatening some of AROB’s outer islands, will pose more challenges in the immediate future.

Image: Buka Passage between Buka Town and Kokopau, Bougainville Island (Source: Christopher Brucker)

Whether Bougainville will become independent by 2025 (or 2027) depends on a growing number of variables that the government in Buka can only partially control. The following months will surely bring lots of challenges that require hard work and tough choices. Despite all these difficulties, the referendum spirit still lingers. Bougainville is a beautiful and peaceful place. The population is united and determined to become independent. A Bougainville Constitutional Planning Commission began meeting in February and is busy figuring out a constitution for the new state. The much-acclaimed reconciliation process is still underway. This summer (which actually was winter in Bougainville), a crucial reconciliation ceremony took place on the edge of the Panguna Mine open pit, signifying the next step in the country-wide healing process as well as “the cessation of all hostilities and activity of the BRA.” A cautiously-managed re-opening of the mine could provide the young state with a solid source of revenue. The potential for tourism is incredibly huge. Bougainville still has friends and supporters all over the world. Let us hope that the latest chapter of Bougainville’s story will give its people yet another reason to celebrate.

Author: Christopher Brucker