In the Footsteps of Conflict and Coexistence: Bosnia and Herzegovina Thirty Years After the Dayton Peace Agreement

Setting out on a journey of inquiry

Thirty years after the Dayton Peace Agreement, Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) remains a laboratory of post-conflict governance – peaceful on the surface yet still grappling with deep institutional and social divisions. For us, students at the University of Tartu’s “Practical Field Research in Conflict Areas” course, this field trip was designed not as a touristic visit, but as an exercise in applied inquiry: to observe how theories of peacebuilding, memory politics, and institutional design manifest in the lived realities of everyday Bosnia and its quest for normalcy amidst contested identities.

Preparation was an essential part of the journey. Weeks before departure, we discussed theoretical frameworks in class, studied the Yugoslav wars, and examined scholarly debates on post-conflict reconstruction. These sessions gave us the intellectual lens to approach what we were about to encounter: a society at peace yet still partitioned by its past. Our preparation thus already required us to anticipate both mentally and intellectually: fieldwork in conflict zones is not about finding answers – it’s about learning to live with complexity.

Image: Bosnia and Herzegovina is welcoming us (Source: Clement Dillies)

Our itinerary stretched from Sarajevo to Mostar and Banja Luka, crossing administrative entities and symbolic boundaries. Along the way, we met professors, diplomats, activists, and ordinary citizens – each offering fragments of Bosnia’s unfinished story. One question that guided our inquiry was deceptively simple: What does peace look like when its institutions are built to preserve division?

Understanding the architecture of division

Our academic journey began at the Faculty of Political Sciences, University of Sarajevo, where Professor Asim Mujkić introduced us to the paradox at the heart of Bosnia’s political system. He asked: “It is quite calm outside – you do not see any conflict, do you?” The question was rhetorical; beneath that calm lies a constitutional framework that has institutionalized ethnicity as the basis of political life.

Mujkić explained how the Dayton system, designed in 1995 to stabilize peace through ethnic power-sharing, has instead entrenched the very divisions it sought to transcend. Elections in Bosnia are effectively intra-ethnic contests, where political competition revolves not around ideas but around belonging. Whilst the Dayton system was designed for ethnic power-sharing, it instead entrenched group boundaries, with politicians incentivized to mobilize voters along ethnic lines. As Mujkić noted, “self-determination has been replaced by ethnic pre-determination.” Minorities such as Jews and Roma people are still excluded from the presidency, a fact condemned by the European Court of Human Rights as incompatible with democratic norms. What began as a pragmatic peace arrangement has hardened into structural discrimination.

Following Mujkić, Professor Jasmin Hasanović placed Bosnia’s constitutional evolution in a broader historical context, explaining how religion, language, and ethnicity have become deeply intertwined, more by historical accident than functional design. He traced the tension between peacebuilding and state-building, arguing that Dayton’s architects prioritized ending violence over designing a viable democracy. The result is a hybrid political order – neither authoritarian nor fully democratic – where overlapping institutions blur responsibility and perpetuate clientelism. “Democracy here,” Hasanović remarked, “is a form without substance: it exists, but it does not perform.”

Professor Dino Abazović deepened the discussion by exploring the interconnection between religion, ethnicity, and politics. He reminded us that Bosnia’s pre-modern governance was based on communal, not national, organization – a structure revived in new form under Dayton. Religion, once a private identity, has become a political marker, while ordinary citizens remain primarily concerned with jobs, stability, and a sense of normal life. “The people,” Abazović observed, “are more pragmatic than their politicians.”

Image: Professor Valida Repovac-Nikšić highlighting developments in civil society (Source: Katharina Buchsbaum)

Subsequent lectures brought memory and civil resistance into focus. Melina Sadiković showed how Bosnia’s war memories are constructed through competing narratives. Institutionalized remembrance – monuments, tribunals, textbooks – interacts with personal trauma and community storytelling. Her key insight was that memory in Bosnia is not about the past; it is a field of ongoing political struggle. Valida Repovac-Nikšić followed with a reflection on the failure of protest movements to translate discontent into reform. Despite widespread frustration with corruption and the stagnation of EU accession, social mobilization remains fragmented along ethnic and entity lines.

Image: Professor Damir Kapidžić warns not to break your head over the complexity of BiH´s constitutional system (Source: Katharina Buchsbaum)

Finally, Professor Damir Kapidžić dissected Bosnia’s “federation within a federation,” an intricate web of overlapping jurisdictions designed to prevent dominance by any single group. What was meant to guarantee pluralism has instead frozen the system into paralysis. Yet, as he emphasized, partition is not a viable alternative – no one wants to reopen the wounds of war. Bosnia, then, survives in a state of “functional dysfunction,” where institutions work just enough to prevent collapse. All in all, these lectures foregrounded what would become a core theme of the trip: the tension between formal democratic institutions and their manipulation to cement ethno-political hierarchies, a system that many acknowledge is broken but few believe can (or should) be quickly dismantled.

The eyes and ears on the ground

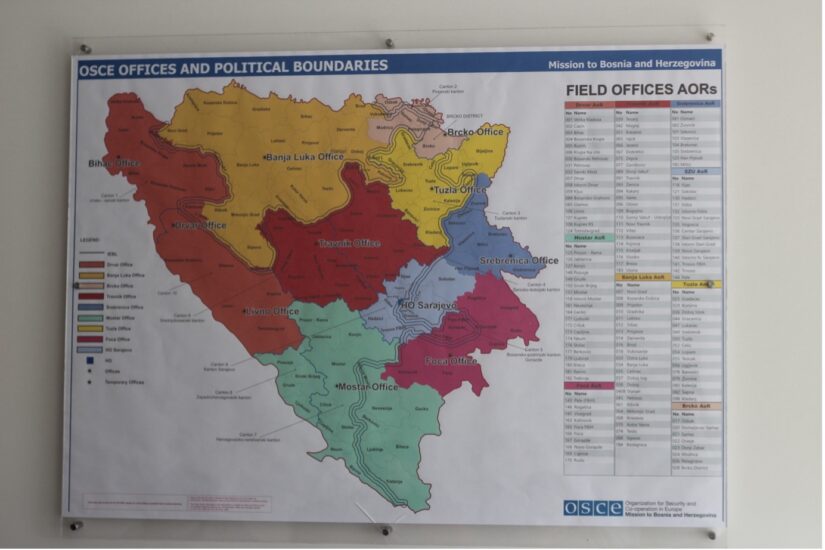

From academia, we moved into the realm of international engagement, where the post-war order continues to be supervised by a dense network of organizations. Our first visit was to the OSCE Mission in Sarajevo, an institution that has operated continuously since 1995 under the mandate of the Dayton Agreement. With over 300 staff, its departments span human rights, security cooperation, and the rule of law. One official described the OSCE as “the eyes and ears of the international community,” a phrase that captures both its persistence and its predicament.

Image: Meeting with the OSCE Mission to Bosnia and Herzegovina in Sarajevo. (Source: Katharina Buchsbaum)

Despite decades of work – ranging from democratic reforms to anti-corruption and counterterrorism – many of the challenges the OSCE addresses today echo those of the 1990s. Officials spoke candidly about the diminishing international attention since 2006 and the difficulty of sustaining reconciliation efforts once donor fatigue sets in. Elections and institutions were prioritized over deeper social healing. The result, they admitted, is a peace that is administratively maintained rather than organically lived.

At the Office of the High Representative (OHR), we encountered the most controversial embodiment of Bosnia’s international oversight. The OHR retains sweeping “Bonn Powers” to impose legislation and dismiss officials – tools of last resort intended to safeguard the peace process. Yet, as we learned from our interlocutor Özgür Önay, these powers are double-edged. They symbolize international commitment but also provoke local resentment. Russia’s refusal to recognize the current German High Representative, Christian Schmidt, has further politicized the office, turning its legitimacy into a geopolitical battleground. Whether Bosnia can transition from externally supervised peace to genuine sovereignty remains an open question.

A similar ambivalence marked our meeting at the Delegation of the European Union. With over €3.7 billion in aid since 1996 and the continued presence of EUFOR peacekeeping forces, the EU is arguably Bosnia’s most invested partner. Yet, as one delegate half-joked, “the EU wants Bosnia more than Bosnia wants the EU.” The country’s constitutional gridlock makes reform painfully slow, while EU conditionality lacks the clarity and incentives to drive real transformation. Enlargement fatigue on both sides has left Bosnia suspended in what one participant called a “permanent pre-accession.”

Image: Map of the OSCE field offices and areas of responsibilities (AoR). (Source: Katharina Buchsbaum)

Our journey north to Banja Luka provided another perspective. There, Christophe Fortier-Guay, Head of the OSCE Field Office, offered insight into governance and reconciliation efforts within Republika Srpska. His team’s work – monitoring elections, supporting the rule of law, and promoting interethnic dialogue – operates in a politically charged environment where international legitimacy is constantly questioned. Key issues included questions around Milorad Dodik’s leadership, along with monitoring attacks on religious institutions, interethnic dialogue, and processes of reconciliation. The OSCE’s democracy-building department emphasized its anti-corruption and good governance mandates, with a special focus on promoting social cohesion and representation for all vulnerable groups – especially given tensions from returning populations after interethnic conflicts.

Discussion also touched on legitimacy crises: local actors frequently reject Christian Schmidt, the current High Representative, as a “colonial” imposition, citing lack of UNSC approval and violation of diplomatic norms, and blaming international oversight for political and institutional instability post-Dayton. Reforms (especially those tied to European integration) face constant obstruction, with key priorities either blocked or manipulated in the name of ethnic representation rather than consensus, leaving BiH’s governance vulnerable to politicization and stalemate. Coordination mechanisms and reform processes reveal how deeply entrenched ethnic vetoes hinder progress and fuel ongoing debate over the very meaning of reform in the Bosnian context.

Image: After the war the “Grateful Citizens of Sarajevo” thanked the international community through this golden, metre tall can of ICAR beef monument. (Source: Katharina Buchsbaum)

Grassroots bridges across divides

If international actors embody Bosnia’s external scaffolding, CSO activists represent its internal lifeblood. Our encounters in Mostar and Banja Luka illuminated the everyday struggles of those working to bridge divides from below.

In Mostar, human rights activist Štefica Galić recounted her city’s painful history. Once the site of fierce fighting between Croats and Bosniaks, Mostar today stands physically reconstructed but socially segregated. Schools, hospitals, and even public offices remain divided by ethnicity — a portrait of a city rebuilt in form but still fractured in spirit, where education, administration, and public life continue to mirror wartime divisions. Galić described how, during the war, she and her husband resisted nationalist propaganda and helped neighbours escape persecution — a stance that later made them targets themselves. Her stories of suffering, displacement, and elite manipulation reminded us that the past is never truly past in Bosnia and Herzegovina; trauma and distrust are renewed with every political manoeuvre.

Image: Human rights activist Štefica Galić standing in front of her memories embedded in resilience and hope. (Source: Katharina Buchsbaum)

A few streets away, the people of OKC Abrašević offered a glimpse of hope. This cultural centre is a vibrant space where young people from different backgrounds gather for concerts, debates, and film screenings — an enclave of normalcy amid enduring polarization, where ethnic and religious identities give way to friendship and creativity. “Here, real names don’t matter. It’s almost strange to ask someone where they’re from.” The message was simple yet profound: sometimes, being human first is its own act of resistance. Still, we sensed the lingering legacy of conflict — younger generations carrying both hope and a cautious willingness to accept bitter compromises for the sake of peace. Bosnia can be seen as a small confederacy of tribes, where peace is maintained less through reconciliation than through exhaustion. One remark summed it up poignantly: “We would eat crap, if it means no more war.” It captured both the trauma and the pragmatism that shape Bosnia’s post-war generation.

Image: Events listed on the walls of the of OKC Abrašević Cultural Centre in Mostar. (Source: Katharina Buchsbaum)

After meeting Tamara Miščević, representing the Oštra Nula NGO mainly dealing with feminist issues, our final activist encounter in Banja Luka took place with Jovana Kisin, a prominent human rights lawyer and advocate. Her account illustrated the continuing vulnerability of minorities and returnees in Republika Srpska. Kisin spoke of harassment, hate campaigns, and a legal system fragmented across thirteen constitutions. “Rights exist on paper,” she noted, “but not in practice.” The activists’ experiences of intimidation underscored the persistence of fear in everyday life. Yet she refused cynicism. Civil society, she argued, remains Bosnia’s most credible source of change: “If you must choose between being somewhat of a colony and being at war, you would rather be the colony – but it is our citizens that care most about this country, and we should aim for change.” Somewhat paradoxically international actors maintain peace from above, yet civil society activists nurture coexistence from below. Their courage lies not in grand gestures, but in the quiet insistence that humanity matters more than ethnicity.

Narratives of power and resistance

Meetings with a local politician in Republika Srpska provided a sobering counterpoint to the activists’ determination. At the People’s Assembly in Banja Luka, Srđan Malzalica represented a worldview shaped by distrust of international intervention. He portrayed the European Union and the Office of High Representative as threats to Republika Srpska’s autonomy, accusing Western powers – particularly Germany – of “neo-imperial” overreach. He decried international oversight as neo-colonial interference, simultaneously crediting RS’s autonomy to externally imposed arrangements and blaming those same actors for post-war sclerosis. The rhetoric invoked historical grievances from World War II and Cold War alignments, framing Bosnia’s current political struggles as a continuation of external domination, deepening scepticism toward the EU and particular member states.

Image: Our meeting with Srđan Malzalica at the People’s Assembly in Banja Luka. (Source: Katharina Buchsbaum)

This stance reflected a broader populist narrative: that Republika Srpska’s sovereignty is under siege, and that integration into Western structures would erase its identity. The irony, of course, is that the very system protecting that autonomy was imposed by foreign negotiators in Dayton. Politics here seems to be less about governance than about the management of resentment. While such narratives resonate with parts of the population, they also reveal the paradox of Bosnia’s statehood: its institutions depend on external guarantees that its leaders publicly denounce.

Listening to these politicians, it became clear that the vocabulary of victimhood remains politically profitable. Invocations of “colonial control,” comparisons to the NATO interventions, and appeals to Russian solidarity serve as both political armour and ideological currency. The result is a perpetual stalemate where every actor claims to defend democracy by obstructing it. What ultimately emerged was a picture of governance as a game of obstruction, where vetoes are wielded as much to block consensus as to defend vital interests, and where leaders justify inaction in defence of an ethnic community that, on the ground, seems to yearn for less politics, not more.

Image: The Foyer of the People´s Assembly in Banja Luka reflects the close association with the motherland Serbia. (Source: Katharina Buchsbaum)

Civilians between memory and resilience

Beyond institutions and politics, Bosnia’s story unfolds in quieter spaces – in markets, bus rides, and street corners. My own observations of everyday life offered an emotional counterweight to the structural pessimism encountered in our meetings: I could perceive a sense of home contrasted with the abstract narratives of broken states or failed integration, encapsulating a mundane heroism of life in post-conflict BiH.

On the road from Sarajevo to Banja Luka, I sat in the front seat of the bus, watching the landscape unfold like a moving tapestry – villages nestled in valleys, children playing near broken buildings, farmers selling honey and homemade juice by the roadside. Despite the scars of war, life pulsed with stubborn continuity. As we were entering Banja Luka, I asked our driver from Sarajevo what he thought of Republika Srpska; perhaps an unintentionally provocative question was then answered surprisingly peacefully – he looked out the window, smiled, and simply said: “I like it.” That understated feeling may have captured something essential about Bosnia: it is something beyond theory or policy that seems to hold the secret of Bosnia’s endurance.

Conversations with students from the University of Sarajevo reinforced this mix of hope and frustration. “We have to leave,” one said. “There’s nothing here for us.” Many Bosnians, and especially the young they told us, remain frustrated by corruption, lack of opportunity, and limited prospects for change within the existing system. They look abroad for hope, “applying for scholarships,” “dreaming of Berlin,” all the while knowing that their aspirations are entwined with the fate of their homeland. Yet as they laughed about their plans, the sense of shared identity was unmistakable. The differences that dominate political discourse seemed almost irrelevant among peers. As Mujkić had suggested in class, the ethnonationalist bubble may still define the system, but it no longer defines the youth.

This everyday coexistence – anchored in the humour that crosses divides or ordinary gestures of kindness – reveals a form of peace often invisible to outsiders. It is not the peace of institutions, but of people who, despite everything, choose to go on living together.

Lessons from the field

Our week in Bosnia and Herzegovina transformed abstract theories into tangible realities. What emerged most clearly was the tension between formal peace and lived coexistence. Dayton’s architecture has ensured stability, but at the cost of flexibility and inclusiveness. International organizations sustain the framework but cannot infuse it with life. Activists and citizens do the opposite – they breathe life into a fragile system, even as they operate within its constraints.

Three lessons stand out.

First, peacebuilding is not linear. Bosnia reminds us that the absence of war is not the same as the presence of justice. The structures that prevent conflict can simultaneously perpetuate inequality. Stability, while essential, is not an endpoint but a condition for deeper transformation. True peace is not just the absence of violence but the presence of justice, opportunity, and the freedom to “be human first.”

Image: Different narratives of the past echo back in the politics of today. (Source: Eiki Berg)

Second, local agency matters. Whether through Galić’s human rights work, Abrašević’ youth initiatives, or Kisin’s legal activism, change in Bosnia emanates from the margins. International actors can support these efforts, but they cannot substitute them. As one OSCE representative put it, “We can build frameworks, but only Bosnians can fill them.” The challenge for BiH – and for those who study and wish to support it – is to build on what already exists: the resilience of local communities, the bridge-builders among civil society, and the unfinished dialogues between memory and hope.

Finally, fieldwork itself is a practice of humility. Walking through Sarajevo’s rebuilt streets, crossing Mostar’s iconic bridge, and hearing the conflicting narratives of Banja Luka forced us to confront the limits of external understanding. Whilst some of us might have come seeking explanations and solutions, we left with more questions and a new appreciation for the lived reality of post-conflict societies. The field does not yield clear answers; it exposes contradictions. And perhaps that is its greatest value.

As we flew home, I thought of the bus driver’s caring words – “I like it.” In a country so often described in terms of division and dysfunction, that simple expression of attachment carries profound meaning. It reminds us that peace is not merely a political condition, but a lived experience – fragile, imperfect, and deeply human. Above all, the experience reaffirmed the value – and necessity – of practical field research. It is one thing to read about conflict and peace from afar, another to walk its streets, to listen, and, perhaps, to carry a little of its complexity home within yourself.

Author: Katharina Buchsbaum