Would Recognition Help Palestine?

The recent decision by several governments to formally recognise the State of Palestine marks a watershed moment in one of the world’s longest and most complicated conflicts. For decades, many Western powers resisted this move, but its growing acceptance signals a profound diplomatic shift. Now, they join the majority of states that over the past decades have recognised the State of Palestine. At the moment, Palestine is recognised by just under 80 per cent of all UN members. While this new wave of recognition does not immediately ease the suffering or halt the destruction in Gaza and the West Bank, it might reshape the longer-term landscape of the conflict.

How do states recognise Palestine together?

When countries act collectively rather than individually, recognition carries more weight. Spain’s earlier attempt to persuade the EU to move together on Palestine faltered, but it later aligned with Norway and Ireland only. Around the same time, Caribbean nations including Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, Barbados, and the Bahamas also extended recognition. Fifteen years ago, a few South American states did the same. These coordinated efforts signal that Palestinian statehood is no longer a marginal demand, but part of an emerging international consensus. Acting together also shields governments from criticism of political opportunism and reframes recognition as a global norm.

Image: The UK government explaining its recognition decision (Source: Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office)

Whereas this wave of recognition is done collectively, that is in coordination, it is not done unilaterally, like the Israeli government or some of its allies suggest. This is because recognition of states is a competence of governments and not something that needs to get the agreement of other states anyway. It is true that for years the practice of many governments was to wait for a peace agreement between the Israelis and the Palestinians before they recognise Palestine. But this was a policy that is rather an exemption to the rule of how states are recognised. The Netanyahu government has also made clear that they won’t agree to a two-state solution settlement anyway. Not only that but the Israeli government’s clear effort to undermine the possibility of a Palestinian state seems to be a main motivation behind this new wave of recognitions.

Image: The notorious ‘security wall’ cutting across the 1967 border line and undermining the territorial integrity of the State of Palestine (Source: George Kyris).

What explains the recognition of Palestine?

This new wave of recognitions of Palestine is driven by acute concerns that Palestinian statehood is under existential threat. Ongoing, Israeli settlement expansion in the West Bank and moves to entrench control over Gaza directly undermine the very territories international law considers as belonging to the Palestinians. The settlements are explicitly mentioned in the statements of countries that recently recognised. The statement by the PM of Canada specifically mentions how the possibility of a Palestinian state and a two-state solution is eroded by settler expansion and violence, including specifically this year’s vote by the Knesset calling for the annexation of the West Bank and the E1 Settlement Plan. If implanted, the plan will divide the West Bank and will also cut off Palestinian neighbourhoods from East Jerusalem affecting the possibility of the Palestinians to claim it as their capital.

At the same time, there is also indignation about Israel’s war on Gaza, the other territory belonging to the Palestinians, and possible plans to also eventually annex it. The UN’s commission of inquiry recently concluded that Israel is committing genocide in Gaza, echoing earlier findings by other bodies. Public opinion has shifted sharply too: in the UK, for example, one of the countries whose government recently recognised Palestine, sympathy for Palestinians has surged from 15% after the October 7 attacks to 37% by mid-2025, while backing for Israel fell. Throughout the world, people have taken to the streets to show solidarity with the Palestinians and this is thought to have motivate the change of recognition stance from governments, like that of Australia’s. Recognition is, therefore, not just a top-down diplomatic gesture. But, rather, it reflects pressure from millions of ordinary citizens demanding governments uphold Palestinian rights. As Palestinian ambassador to the UN Riyad Mansour put it, ‘Millions of people in these nations are pressuring their governments to do more in order to […] recognize the legitimate national rights of the Palestinian people […] to statehood’.

Image: People of Mostar expressing solidarity with Palestine (Source: Eiki Berg)

The question of legality

Critics, particularly Israel and its allies, argue that Palestine fails to meet the requirements of statehood, such as a clear territory and population or a government. These claims do not hold for a series of reasons. First, there is no agreement between analysts and scholars as to whether Palestine fulfils these criteria. For example, some argue that Palestine does not fulfil the Montevideo criteria, such as that of having a defined territory. It can be argued, however, that the territories of Gaza and the West Bank are defined as those of the State of Palestine in numerous international documents—from the 1947 UN Partition Plan, through the 1988 declaration of the State of Palestine now widely recognized, to more recent judgments of the International Court of Justice.

The fact that, in practice, Palestinians do not control parts of these territories because of Israel’s occupation is a secondary issue here (though of course paramount for the everyday lives of Palestinians and the viability of their state), in the same way that the occupation of eastern Ukraine has not made Ukraine less of a recognised state in the eyes of the international community. And more generally, the Palestinian right to a sovereign state has long been affirmed by the international community, which strengthens the legitimacy of this new wave of recognitions. And, finally, there are no criteria based on which states are recognised. Recognition is a political act, and many nations have been recognised before they had clear borders or functioning governments. Ironically, the US itself recognised Israel in 1948 despite criticism that this was a premature move because the borders of the state were not clear.

Does recognition reward Hamas?

No, and this is because recognizing a state does not mean supporting its government, and because all acts of recognition have been accompanied by explicit statements condemning Hamas. In analyses of statehood, it is a well-established wisdom that the recognition of a state and a recognition of a government are two different things. Acknowledging a state is distinct from endorsing its current rulers. Afghanistan, for instance, continues to be recognised despite most governments refusing to legitimise Taliban rule. Libya’s Government of National Stability controls most of Libya but is widely not recognised by states that do not question the existence of Libya as a state. Finally, the fact that Netanyahu is under arrest warrant of the International Criminal Court for war crimes and crimes against humanity has not resulted in states withdrawing their recognition of the State of Israel and its people. Recognising a state is about existence of the state, which is different to recognising a government, which is about representation.

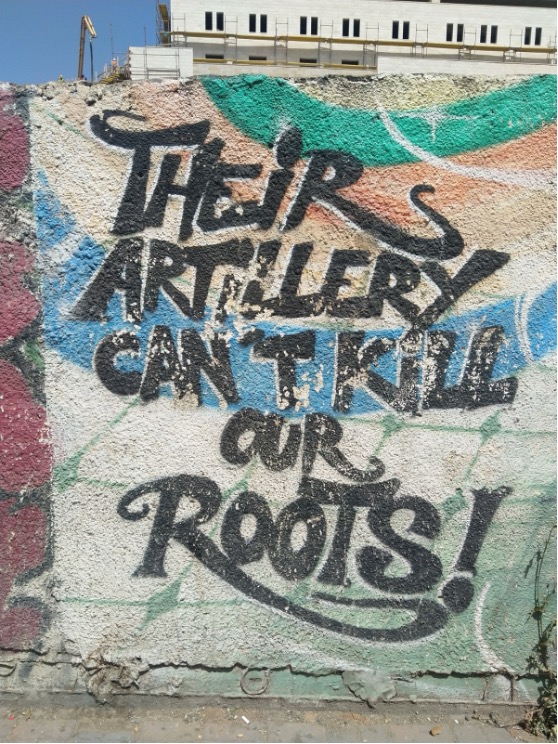

Image: Resistance has become a defining feature of life in the Palestinian-held territories (Source: George Kyris)

Despite this distinction, states that recently recognised Palestine explicitly mentioned that Hamas should be excluded from future government roles and that the Palestinian Authority should be reformed and organise free elections without Hamas. Some see this as ‘conditional’ recognition, but the language is unclear, and no state has said that they will withdraw their recognition of these steps are not taken. Only France said that, although it recognises the state of Palestine, it won’t open an embassy until Hamas releases the hostages. Exactly because the recognition of a state is different to the recognition of a government, the attachment of conditions to a right that is afforded to other states unconditionally seems excessive. Yet, it allows recognising states to support Palestinian sovereignty without legitimising armed groups or undermining efforts toward a negotiated settlement. It also counters Israeli claims that recognition emboldens terrorism.

The impact of recognitions

Diplomacy has repeatedly shown its limits in halting of the human catastrophe that Israel’s war has brought on Gaza, leaving little cause for optimism. Recognition can be seen as the boldest available gesture from governments unwilling to impose sanctions or other real costs on Israel for its ongoing war, occupation, and dismantling of the two-state possibility.

Yet, symbolic steps still matter. Recognition enhances Palestine’s diplomatic weight and could encourage more states to follow suit. The new wave of recognition also expands Palestine’s access to international fora, legal institutions, and aid. The 2011 decision by the UN General Assembly to grant Palestine observer status, for example, paved the way for the International Court of Justice to hear the genocide case against Israel and the International Criminal Court to issue arrest warrants against Israeli and Hamas leaders alike.

The diplomatic consequences for Israel and its allies could also prove significant. Following the recognition of Palestine by France and the UK, the US now stands isolated as the only permanent UN Security Council member refusing recognition. Recent headlines highlighted Washington as the lone veto against resolutions demanding a ceasefire, aid for Gaza and the release of hostages. Israel and its backers will increasingly find themselves in a shrinking minority, vulnerable to criticism from human rights bodies, international institutions, and global public opinion. While such isolation may not sway current policymakers, especially from the US administration that is breaking with long-established conventions of diplomacy, over time it could reshape diplomatic calculations and revive pressure for negotiations towards a two-state solution.

Indeed, more widespread recognition shifts the international conversation even more towards the need to ensure Palestinian statehood. Almost forty years after Palestine’s declaration of independence, recognition by some of the world’s most powerful states signals a profound change in international politics. It underscores how strongly both governments and citizens in many countries now feel about supporting Palestinian statehood in the face of Israel’s ongoing occupation. The question, therefore, is no longer whether Palestinians are entitled to a state, but how to make that state viable through dealing with core issues such as borders, security, Jerusalem, refugees, governance. Still, the irony is that such a move comes at a time where Israeli government’s assault on Palestinian land and people is unprecedented and seriously undermining the viability of a Palestinian state in practical terms.

In the face of fading hopes for a two-state solution, alternatives are entertained, but these should ensure the Palestinian right to statehood and sovereignty must be respected. And, in the end, recognition cannot stand alone, especially in the shorter term. To matter, it must be coupled with sustained international efforts to end the war in Gaza, hold perpetrators accountable, and relaunch genuine negotiations. Only then can recognition become not just a symbolic step, but a meaningful move toward justice and sovereignty for the Palestinian people.

Author: George Kyris