Why States Are Recognizing Palestinian Statehood After October 7th

Since the beginning of the War in Gaza and Israel, nine additional states have recognised the “State of Palestine”: Barbados, Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, The Bahamas, Ireland, Norway, Spain, Slovakia, and most recently Armenia. This means that now 146 (out of 193) UN member states officially recognise Palestinian statehood. But why do states recognise the “State of Palestine” when its government has become most vulnerable since the Oslo Accords? And what is the reasoning for the timing of their recognition?

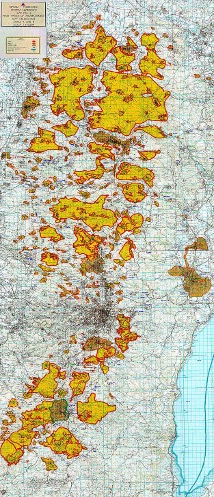

Image: PA territory according to the historical map used in the Declaration of Principles (Oslo I)

Palestine’s bi-institutional foreign policy apparatus

Out of all the de facto states featured on this website, Palestine is a peculiar case. Unlike Abkhazia, Transnistria or Somaliland, the “State of Palestine” neither has unified government structures nor effective control over its claimed territory. Although the Palestinian Authority (PA) represents the de jure government of Palestine, it is only exercising limited self-rule over discontinuous parts of the West Bank. Gaza is already outside of the PA’s reach since Hamas established its control during the inner-Palestinian conflict of 2007. Even in the areas where the Taba Agreement (also known as Oslo II) awards the PA full autonomy in the West Bank, local militias and Islamic splinter groups have started to defy the control of the government in Ramallah. Given the absence of PA law enforcement, Israeli security forces engage in more and more incursions into PA territory to combat these groups (The Economist, 2023). Already before October 7th, analysts began to doubt whether we are witnessing the “end of the Palestinian Authority”.

The picture is further complicated by the institutional jumble associated with the “State of Palestine.” The Oslo Accords established the PA as a proto-government for a proto-state. The different agreements outline various competencies of the PA to be exercised on limited territory. However, the PA is explicitly barred from conducting foreign affairs under Article 3(b) of Annex II of the Declaration of Principles (Oslo I) and Article IX(5)(a) of the Taba Agreement (Oslo II). Instead, the PLO was to continue to represent the Palestinian people toward the international community until a Palestinian state was formally established.

Nevertheless, the PA has a “Diplomatic Corps Law” which governs the conduct of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Expatriates (MoFA) and the Palestinian diplomatic missions abroad. At the same time the PLO maintains six departments with the capacity to conduct foreign affairs. In the resulting double structure, the PLO remains the sole legal body with the capacity to negotiate international agreements on the behalf of the Palestinian people, whereas the PA embodies the effective governance structures of Palestinian self-determination already in place. This bi-institutional foreign policy apparatus is currently bound together by Mahmoud Abbas, who is both president of the PA and the chairman of the PLO executive committee. However, both institutions remain formally divided and suffer from poor coordination. This divide is also reflected in the diplomatic corps itself, with some viewing themselves more as “PLO representatives charged with representation and liberation, and newer appointees who function more like bureaucrats.” Entering into formal diplomatic relations with the “State of Palestine” practically means to enter into relations with the bi-institutional arrangement of different PA and PLO bodies. Given the administrational and legal disarray, as well as the territorial discontinuity and issues with effective governance, why are states now recognising the supposed “State of Palestine”?

Recent recognitions

The nine states recognising Palestine this year can be grouped into two geographical clusters: A Caribbean and a European one, with Armenia standing apart as a distinct case. Despite their individual differences, the recognitions by all nine states share some characteristics. All of them maintained good, or at least neutral relations to Israel before their recognition of Palestine and cite the promotion of peace as a reason for their recognition. Most official statements include a notion of the war in Gaza and call for a ceasefire. Many also refer to a resolution of the UN General Assembly (UNGA) calling for full Palestinian UN membership to legitimise their recognition. Besides these commonalities, the official statements and explanations vary significantly in length, depth and content.

The Caribbean

The Caribbean states were the first group to recognise, with Barbados taking the lead on April 19. The Minister of Foreign Affairs and Foreign Trade of Barbados framed the recognition as the correction of an error. Minister Symmonds explained “there is an incongruity and inconsistency [regarding the lack of recognition] because ‘how can we say we want a two-state solution if we do not recognise Palestine as a State?’”. Further, he mentioned that talks about the recognition preceded October 7 (ibid.). His assertion that bilateral ties to Israel would not be affected by the acknowledgement of Palestinian statehood, was surprisingly echoed by Israeli Ambassador Itai Bardov, although he voiced his discontent with the decision.

Jamaica, Trinidad & Tobago as well as the Bahamas followed suit with their recognitions within a month. Although Jamaica and Trinidad & Tobago do not officially refer to the recognition of their neighbours, the Bahamas mention “the Caribbean Community’s consensus on this matter” in their statement. The Bahamas was the last member of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) to recognise the “State of Palestine” after Guyana did it first in 2011.

The prior consultation between Barbados and Palestinian officials in September 2023 and the successive recognitions by CARICOM members since 2011 suggest that the Caribbean recognitions were the result of a process that started before October 7 and were, at least in part, driven by regional foreign policy harmonisation between the members of CARICOM. This interpretation is further underlined by Minister Symmonds’ remarks on the occasion of the formal establishment of diplomatic ties between Barbados and Palestine:

“We are also proud of whatever small impact our decision to take this step may have had in the wider geopolitical sphere. Barbados’ decision was closely followed in the region […]. As a result of these developments, all CARICOM countries now recognise Palestine.”

Image: Riyad H. Mansour (Palestine) and Francois Jackman (Barbados), representing their respective countries at the UN, shaking hands after signing the document establishing diplomatic relations between their two countries in New York (Barbados Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Foreign Trade, via CNG Media)

Europe

The European cluster recognised Palestine in two waves, with Spain, Ireland and Norway recognising on May 28th and Slovenia following on June 4th. These four were the next European states to recognise Palestine after Sweden’s recognition 10 years ago. While most former members of the Eastern Bloc had already recognised Palestine in 1988, Western and Southern Europe usually preferred to follow a policy of conditionality. According to this logic the recognition of a Palestinian state was viewed conditional on the outcome of a successful peace process with Israel, to provide the Palestinians with an incentive to negotiate.

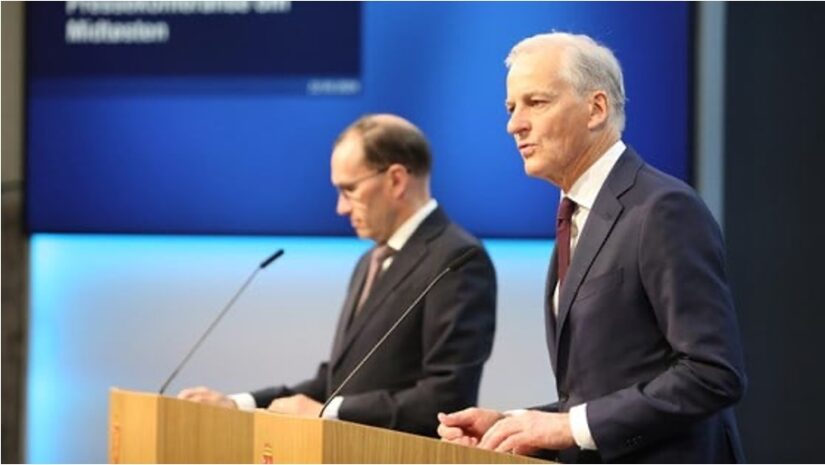

Norway, Spain, Ireland and Slovenia now broke with this policy citing its ineffectiveness to promote peace in the region. In his article for Politico, Norwegian Prime Minister Jonas Gahr Støre inverts the old logic of conditionality:

“Norway has been consistent in its belief that there will be no peace in the Middle East without a two-state solution. And there can be no two-state solution without a Palestinian state. In other words, a Palestinian state is a prerequisite for achieving lasting peace in the Middle East.”

Ireland and Spain also argue that they recognise Palestine in order to “keep the destination of Two-State-Solution alive.” Claiming the formal recognition of Palestine as a prerequisite to, rather than a reward for a peace process leading to a two-state solution marks a remarkable shift of perception. The Palestinians are no longer perceived as the spoilers to the peace process, Israel is.

This shift might be linked to the immense loss of civilian lives and infrastructure in Gaza resulting in reputational costs for Israel. The statements tacitly condemn Israel’s conduct of the war while also acknowledging Israeli casualties and the remaining hostages. For example, Spain’s Foreign Minister Albares stressed “that we cannot wait any longer” in regards to a peace process, adding that:

“Hundreds of thousands of people, children and entire families are right now as I speak deprived of food, water, medicine, shelter and, above all, they are in fear for their lives […] violence has taken the lives of 1,200 Israelis, including two compatriots, and more than 35,000 Palestinians.”

Another reason cited by the four European states for recognizing Palestine is to support Palestinian moderates. All four states have condemned Hamas’ attack on October 7th and mention their condemnation of Hamas in their statements. Hamas is neither part of the PA or the PLO as both institutions are effectively controlled by Fatah, the political party headed by Mahmoud Abbas. By legitimising these institutions (as they practically are the Palestinian state) through recognition, the four European states seek to weaken Hamas in the intra-Palestinian power struggle. Regarding the aforementioned weakness of the PA, it is questionable whether this support is simply too late or still badly needed.

Image: Prime Minister Jonas Gahr Støre and Minister of Foreign Affairs Espen Barth Eide at the press conference when they announced that Norway recognizes Palestine. (Mathias Rongved/MFA)

Given their historic ties to the conflict, it is no coincidence that Ireland, Spain and Norway specifically took a lead in this matter. Oslo and Madrid played important roles in the peace process during the early 90s by facilitating the negotiations leading to the Oslo Accords. They are also both governed by progressive (or at least left-leaning) governments that tend towards a more pro-Palestinian stance. In Ireland, people across the political spectrum see the Palestinians’ struggle for self-determination as reminiscent of their own fight against British occupation in the 20th century. In combination with the horrific images from civilian casualties in Gaza, Palestine became an important issue for voters in these countries.

The recognitions of all four countries happened directly before the European Parliament elections on June 9th. Given the pro-Palestinian sentiments among the electorates of the respective governments these recognitions can be conceived of as domestic-driven foreign policy. In this logic, the governments recognised Palestine at this specific timing in order to gain votes in the European Parliament elections – and not for reasons endemic to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

This explanation might be complicated, to say the least, by the fact that the recognition of Palestine has been on their agenda long before the EP elections and even before October 7th. Spain is trying to convince its European allies at least since 2018 to acknowledge Palestinian statehood. The Norwegian Stortinget started hearings on the decision which enabled the government to recognise Palestine already in May of 2023. Slovenia’s parliament already tried to recognise Palestinian statehood in 2018, but failed to organise a majority in the foreign affairs committee and Ireland’s government included the recognition in their coalition program following the 2020 elections. Hence, the decision to recognise Palestine is likely to reflect considerations beyond the campaign around the European elections.

Armenia

Armenia’s recognition of Palestine is different from the European and Caribbean recognitions in that it is linked to the conflict around Nagorno-Karabakh. Armenia’s prior foreign policy was to not recognise disputed territories, or sovereignty claims due to its own involvement in the Karabakh conflict. But after Azerbaijan violently established its control over the territory, Prime Minister Pashinian officially acknowledged Nagorno-Karabakh as part of Azerbaijan, thus opening the door for other recognitions.

The recognition of Palestine was a convenient opportunity for Armenia to get back at Israel for their support of Azerbaijan with almost no associated costs for Armenia. Armenian exports to Israel make up less than 1% of the total export volume and the country has no import dependencies vis-à-vis Israel. Instead, Israeli weapon shipments to Azerbaijan and the long-standing security cooperation between both countries proved to be instrumental for the Azerbaijani victory over Armenia. By recognising Palestine, Armenia also managed to score a rare commendation by the outspokenly pro-Palestinian Turkish government, embarrassing Azerbaijan in front of its most important ally.

Outlook

In conclusion, the recent recognitions of the “State of Palestine” reflect a combination of geopolitical motivations and domestic considerations. While the Caribbean states appear driven by regional foreign policy alignment, the European recognitions represent a shift in their approach to the conflict. The European elections in June can explain the concrete timing of the recognition, but just as with the Caribbean states, the policy processes leading to the recognition of Palestine started before October 07, 2023. Hence, these recognitions can also be understood as the beginning of a paradigmatic shift in Western-oriented states’ perception of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, especially regarding the process of its resolution.

Whereas the dominant (Western) understanding of the conflict views Palestinian statehood as a reward to incentivise Palestinian participation in a peace process, these recent recognitions view Palestinian statehood as a prerequisite to the two-state solution. This shift in perception can be attributed to the ever more vocal Israeli rejection of a Palestinian state and the reputational costs that Israel suffers from its conduct of the war in Gaza. The Knesset recently passed a resolution further underscoring the rejection of any Palestinian state “west of the Jordan river,” which is not helping Israel’s standing with most of its allies who, at least by declaration, still support a two-state solution.

Image: The Israeli Foreign Minister, Israel Katz, mocking the Spanish government on Twitter (X).

Whether this shift in perception disseminates and subsequently translates into action by other members of the Western camp remains to be seen. Israel tries to dissuade band-wagoning by imposing restrictions on diplomats as retaliation for the recognition of Palestine, sometimes even mocking them on official social media channels. Only time will tell whether this tactic actually deters others from recognising Palestine or even further deteriorates others’ trust in the Israeli administration.

Author: Tobias Sauer