Kosovo and the Anxiety in “Colorful” Times for International Politics

On 9 February 2025, Kosovo held its first-ever regular elections after a government’s full term in office ever since it declared its independence in 2008. This was largely possible due to Lëvizja Vetëvendosje (LVV’s) victory in the 2021 elections where it managed to win roughly 51% of the votes – something unparalleled in Kosovo’s proportional electoral system where around 30 political parties compete. The majority vote allowed LVV to form a government by itself and, under the Prime Minister, Albin Kurti from LVV, rule for a full 4-year government term.

LVV’s single-handed rule brought a sense of government stability, but it also enabled it to deal with a few challenges that appeared in the last 4 years in a more assertive manner than previous governments did. Most importantly, LVV’s government dealt a blow to Serbia’s previously unchallenged informal authority over the northern part of Kosovo, when over 3 dozen heavily armed Serb insurgents, both from the northern part Serb-dominated area of Kosovo and Serbia itself penetrated Kosovo. Usually, to deal with such extreme events, previous governments followed a norm to not respond without coordinating with what they called ‘allies’ of Kosovo, such as the QUINT1.

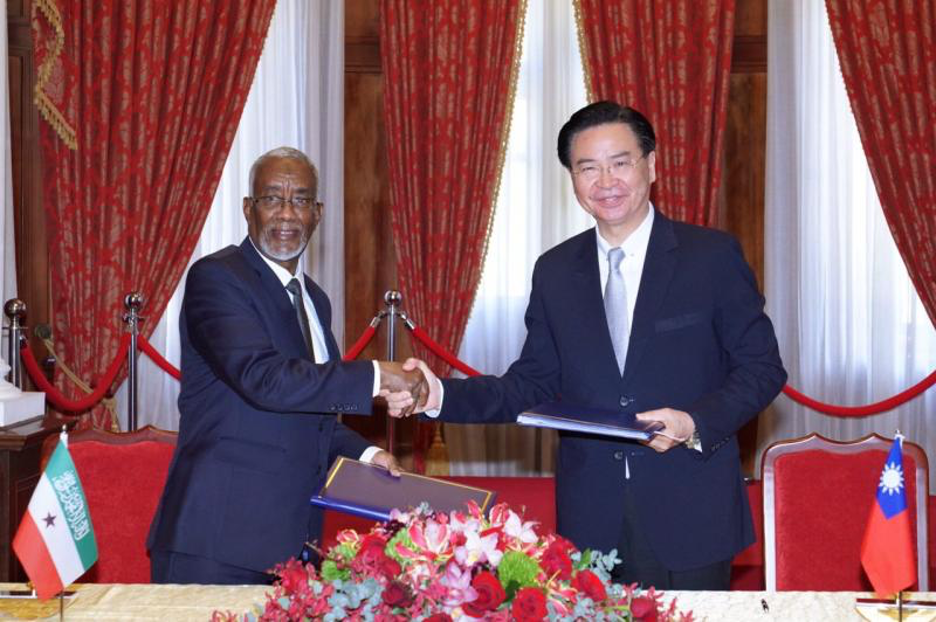

Image: Albin Kurti addressing his supporters after the closure of polling stations (Source: Florion Goga, Reuters)

Kurti wasted no time to play by the norm; he immediately instructed the Ministry of Interior’s special police units to respond to the Serb armed insurgency. The result of Kurti’s actions outside the norm was that Kosovo managed to kick the insurgents out of its territory, detain what they could on the way, and most importantly establish a permanent coercive apparatus in the northern part of the country. This was unprecedented as no other government before, including the United Nations Administration in Kosovo (UNMIK) during its rule in Kosovo, from 1999 – 2008, could establish such assertive control. The Serb insurgency, whatever speculatively their goals may have been, provided Kurti with an opportunity to penetrate the ‘unruly’ northern part of the country. Many Serbian state parallel institutions were closed, including Serbia’s informal security apparatus that had been present in the areas in the past quarter of a century.

Moreover, Kurti also appeared to be more assertive as a party in the EU-facilitated dialogue between Kosovo and Serbia. Surely, he did make quite a few concessions, to everyone’s aw in Kosovo, but the ones which went unacknowledged by the EU or Kosovo’s ‘allies’. Even before the fall 2023 insurgency in the north, the EU presented several (mainly funding-related) sanctions on Kosovo, or as the EU calls them ‘the measures’ to make Kurti concede to Serbia more. The EU sees a partner in Serbia’s President, Aleksandar Vucic, despite the latter’s authoritarian-bent ruling style over Serbia.

The 2025 election results: what may we speak of?

All the votes have been counted yet not confirmed as this piece is being written. Not much will change from the preliminary count, other than the Kosovo Albanian Diaspora vote to surely add a parliamentary mandate or two for LVV. With the present results, Kurti’s LVV managed to get about 41% of the entire vote share, falling roughly 10% short of the party’s majority victory in the previous elections. Partia Demokratike e Kosovës (PDK) much related to the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) got about 22.3%, while Lidhja Demokratike e Kosovës (LDK) much related to the late pacifist president, Ibrahim Rugova, won about 17.5% of the share. In other words, Kurti’s LVV still holds more votes than the following two runner-ups combined.

Unlike the previous term, however, should Kurti want to create a government it is clearly going to happen with a coalition partner, an inevitable pathway of which he is not a fan. In sum, the creation of the next government might take some months, regardless of ongoing international upheavals, and should it be constituted it will be not as stable as the previous one when LVV had the chance to rule by itself.

The above election results reveal many patterns: the popular assessment of Kurti’s previous government on domestic matters, but also of his dealing with the northern part of Kosovo and Serbia itself. What is interesting to tap into is how Kurti’s actions in dealing with Serbia and the Serbs in northern Kosovo might have affected voting patterns exactly in Serb-majority areas in Kosovo both among Serbs and Albanians.

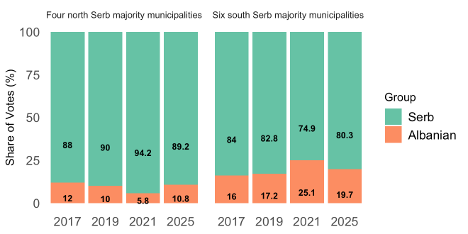

Data from the past four election cycles show that in the northern Serb majority municipalities, the vote share for Albanian political parties was in constant decrease, except for the recent 2025 elections. Kurti’s actions in the north may have motivated Albanian voters in the Serb majority municipalities in the north to go to the ballots. When it comes to southern Serb majority municipalities, there is a slight but consistent trend of a decrease in Serb voters and by similar margins increase in Albanian voters. The patterns may suggest slow demographic changes that may be taking place in Serb-majority municipalities in the south.

Image: Serb and Albanian parties’ vote share in Serb majority municipalities

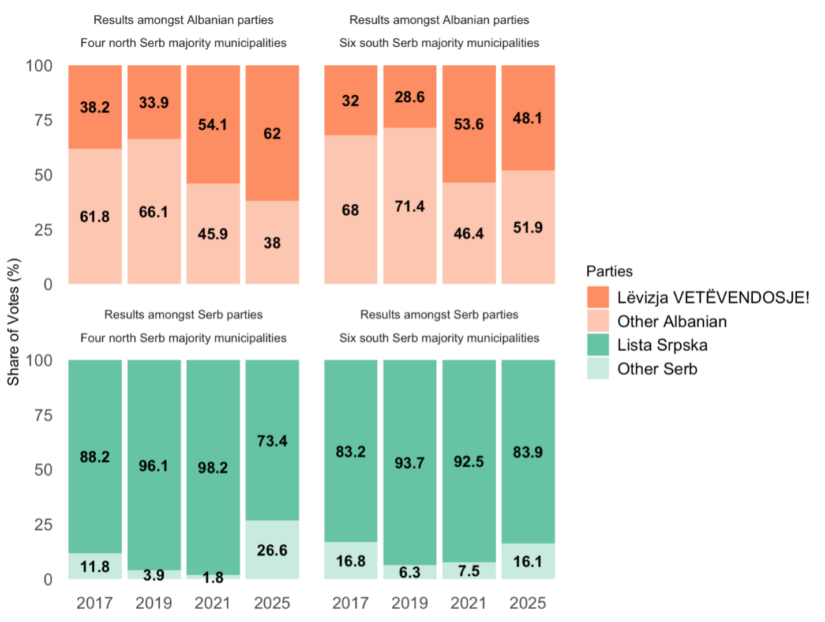

Another pattern to note from existing data, including the recent elections is one which indicates, on the one hand, an association between Kurti’s assertive actions in the northern part and his party’s growth in that area among the Albanian voters. On the other hand, the most dominant Serb party, Lista Srpska (LS’s) withering support in the north. LS usually used to have around 90% of Kosovo Serb votes, with the 2025 elections being an exception whereby, especially in LS’s stronghold in the north, they shrank to about three-froths of Serb vote, giving way to other Serb political parties to gain over a quarter of the votes in the area2. This is not bad news for Kosovo Serbs, for their political power scene may reflect plurality and debate.

Image: LVV and LS vote shares among their co-ethnics

Kosovo and the ‘colorful’ international politics

Kosovo’s elections took place around three months after the US presidential elections. The victory of Donald Trump in the United States and his major foreign policy shifts add, like in other parts of the world, unpredictability in Kosovo’s relations with Serbia but also its place in regional politics. Clearly, the new US administration is after pacifying and likely allying, albeit informally for now, with Russia to try to curb the rise of the former’s power competitor – China. At present, Kosovo can be captured by the US radar of its interests in world politics as much as random birds in the air can be captured by standard US military radars.

However, should the war in Ukraine end on the US’s terms (which might mirror Russia’s terms) it might impact the Balkans to some extent, though the region does not seem to be a priority for the United States. Rightly so, from the new US President’s perspective and his domestic and global ambitions of MAGA, evidence would suggest, that the Balkan region is rather poor and thus costly to deal with. It provides no meaningful return to (economic or political) investment.

Trump appointed Richard Grenell as his envoy for ‘special missions’. Grenell was involved in Kosovo-Serbia negotiations during Trump’s first term, which led to some agreements that so far have been as much worth as a random pen one finds in an abandoned office drawer. Grenell does not fancy Albin Kurti; it is both obvious and well-known that going against Kurti has become Grenell’s personal mission. He likes to tweet about it, much more often than one could imagine a ‘special envoy’ to the US President to have the time. Should Grenell take over the Balkan interest side of the United States for some reason, it can be challenging not so much for Kurti as it can for Kosovo. At present, anything we say more can be highly speculative as Grenell is busy with Latin American missions.

The European Union has recently appointed a new facilitator for the Kosovo-Serbia dialogue, replacing Miroslav Lajcak with Peter Sørensen. There are voices in the EU that, to some extent rightly suggest, that Sørensen should not open new issues in the negotiations between Kosovo and Serbia but rather focus on the implementation of the already agreed terms. However, it is challenging to know what Kosovo and Serbia have agreed on. Some documents make it clear, but there are no documents or just some bulleted point documents that feature as agreements.

I suggest Sørensen will not be able to do much for as long as he stays in the position. It will take some time for the European Union to come to terms with the shock that the United States is seeking, for now informal, alliance with Russia. Under shock, not much can be done. To calm down and come to terms with the reality usually takes some time. The EU’s focus will be strongly pointed towards its eastern front rather than its southeastern one – like never before. There is little the EU can do in the Kosovo-Serbia negotiations. The EU is confused about how to defend and secure itself; it does not provide assurances as a credible conflict facilitator in other parts of the world including its immediate area.

During his term, and before Trump was elected, Albin Kurti was working very hard to increase Kosovo’s defense budget, perhaps quadrupling it during his 4-year term. He has already secured the purchase of about 250 Javelin missiles from the previous US administration. He also managed to and has been quite immersed in plans of rejuvenating a munitions factory in cooperation with Turkey. Unfortunately, it shall be the way to go, for it appears that trusting security guarantors alone can be costly at some point.

Author: Shpend Kursani

1 The United States, The United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, and France

2 The data presented above are all based on the raw data from Kosovo Elections Commission. For current 2025 count here: https://rezultatet2025.net/en/, and for previous ones here: https://kqz-ks.org/an/results/kosovo-assembly-elections/