The Different Manifestations of Territorial Partition in South Africa

The state of South Africa was established in 1910 after four British colonies (two of which had previously been independent Boer republics) agreed to form a union with the blessing of their imperial overlord. The Union of South Africa was a pigmentocratic state founded by representatives of the minority white population of the four entities, and political power remained the preserve of South Africa’s white minority until 1994. In that year the black majority took power in a new non-racial democratic order. In both eras South Africa experienced the politics of territorial partition, but in profoundly different forms.

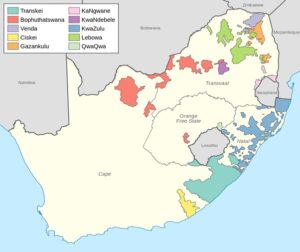

Since the late 1950s South Africa’s white rulers tried to accommodate the political aspirations of the majority black African population by granting them self-rule and even independence in ten so-called black homelands (widely labelled ‘Bantustans’) for the different ethnic groups. The homelands policy, also styled separate development (a supposedly progressive variant of apartheid), was an expansion of the long-standing policy of setting aside ‘reserves’ for exclusive occupation by black Africans. By providing the different ‘Bantu’ peoples with opportunities for self-government and eventual independence in their ‘own’ territories, the black African majority would forfeit any claims to political rights in so-called white South Africa; this would ensure the continuation of white rule over the remaining 85% of South Africa’s territory.

From Black homelands to ‘independent states’

Four black homelands were granted independence under South African law: Transkei in 1976, Bophuthatswana 1977, Venda 1979 and Ciskei 1981. The TBVC states, as they became known in South Africa, met the basic requirements of statehood under international law, namely territory (ranging from Transkei’s 44,630km2, roughly the size of Estonia, to Venda’s 6,300 km2 that is comparable in size to Brunei); population (the largest resident population – within the territory – was Transkei’s with 1.65 million people at independence, and the smallest was in Venda with 600,241); government (including constitutions, legislatures, executives and judiciaries), and each independent homeland aspired to and arguably possessed the capacity for engaging in international relations.

Advocates of separate development likened the policy to the decolonization occurring in European empires elsewhere in Africa. By allowing homeland independence, the government at the time hoped that the ‘decolonization’ of South Africa would find favour in the international community and reduce external pressure on South Africa over apartheid. It was wishful thinking. The four purported states ran up against a brick wall of collective non-recognition, leaving only South Africa to recognize their statehood. There was also mutual recognition of independence among the four sister states. All the while South Africa’s international ostracism over the continuation of white minority rule intensified.

Image: The TBVC states together with six other ‘homelands’ (Source: Htonl)

Their very origins condemned the TBVC states to contested statehood and severe international isolation. They were internationally regarded as the illegitimate creations of a policy – apartheid – that the United Nations declared a crime against humanity. (In 1973 the UN General Assembly adopted the Convention on the Suppression and Punishment of the Crime of Apartheid). The Assembly and Security Council repeatedly condemned apartheid, including the creation of Bantustans, and urged member states not to recognize the entities’ statehood. The fear was that such recognition would amount to the international legitimization of apartheid. The fact that the TBVC states’ excision from South Africa meant that they were freed from direct white control and apartheid, cut no ice with the world community.

The top-down ethnic-cum-territorial fragmentation of South Africa violated another principle of international law and an article of faith in Africa: inherited colonial borders must be preserved when conferring independence. In South Africa’s case the inviolable borders were those demarcating the Union of South Africa in 1910. Another principle that was breached by granting homelands independence from South Africa, related to self-determination. The South African people as a whole were entitled to self-determination, that is, the right to freely determining their form of government. Apartheid denied the black majority that right and moreover tried to confine them to ethnic enclaves and so entrench white rule over the rest of South Africa.

When Transkei became the first ethnic homeland to assume independence, South Africa had already experienced considerable international isolation due to apartheid. The TBVC states were born into the international adversity of their parent state. Transkei, Bophuthatswana, Venda and Ciskei were not the only ethnic homelands created by the South African government. There were six others, which showed no interest in taking independence. The ‘Bantustanization’ of South Africa was undone in 1994 with the end of apartheid and white rule. The TBVC states were absorbed into the provinces of the new South Africa.

Post-apartheid separatism

The 1996 constitution of democratic South Africa does not recognize the existence of any ethnic groups or homelands and the ruling African National Congress (ANC) eschews the notion of ethnic fragmentation. To overcome the divisions of apartheid, the government is deeply committed to nation-building and a new South African identity that overrides ethnic and racial affiliations. The new South Africa has, however, not been spared separatist tendencies. The very fact of ANC rule is, paradoxically, the main reason for two very different quests for partition in South Africa today. Each expresses serious disaffection with the political status quo.

The first case is the small private town of Orania in the Northern Cape Province, established and settled exclusively by Afrikaners (white Afrikaans-speakers) in the early 1990s. Purposely located in a vast and sparsely populated province, the founders of Orania envisaged it as the basis for a future volkstaat and safe haven for Afrikaners in a black-ruled South Africa. With a present population of 1,600 people, the town is still run by its own representative council. Although falling within the boundaries of an officially installed municipal council, Orania operates completely independent of that authority under an interim agreement between the town and the central government. While Orania’s final legal status has yet to be determined, the entity is holding out against inclusion into the statutory system of local authorities dominated by the ANC and non-Afrikaners. The ANC government for its part is tolerating but not approving this all-white, self-ruled private settlement. Orania is meanwhile expanding its territory, economy and population, but has scaled down the founding dream of a future Afrikaner state to a more plausible aim of developing into a city, possibly along the lines of a special economic zone under private control.

Image: “Welcome to Orania” (Source: BBC News)

The second and more serious challenge to the prevailing political order is presented by an independence movement in the Western Cape Province. Of South Africa’s nine provinces, the Western Cape is the only one not ruled by the ANC, which is in power nationally and in the remaining eight provinces. Governed by the opposition Democratic Alliance, the Western Cape is South Africa’s best governed province by far; most of the others experience endemic poor governance at both the provincial and local levels where the ANC holds sway. The Western Cape’s demographic composition does not reflect the national profile either: of South Africa’s total population of 60 million, 80% are black African, 9% are Coloureds (mixed race), 8% whites, and Indians and other races are around 3%. Black African languages are consequently predominant in South Africa, spoken by roughly 76% of the overall population, followed by Afrikaans (the mother tongue of 13.5% of the total population) and English (9.6%). In the Western Cape, by contrast, Coloureds constitute nearly 50% of the provincial population of 7 million, followed by black Africans at 33%, whites roughly 16% and Indians at 1%. Afrikaans is the first language of approximately 50% of the population of the Western Cape. A further distinguishing feature is that Cape Town, the province’s capital, is South Africa’s mother city and the Cape of Good Hope was the site of the landing of the first European settlers in the mid-17th century. Turning to the political situation, the ANC’s average level of voter support in the Western Cape since 1994 has been 36%, declining to 29% in last year’s general election. The ANC, separatists thus argue, has neither the political nor moral right to extend its writ to the Western Cape.

Image: Cape Party’s Freedom march (Source: Ineng)

The Cape Independence Advocacy Group, one of the two main civil society organizations constituting the Western Cape independence movement, recently commissioned an opinion poll in the province on the issue of independence. Roughly 36% of the respondents wanted an independent Western Cape, while 47% favoured a referendum on the issue. Instructively, 53% of Democratic Alliance voters supported independence outright, whereas 64% of them preferred a referendum on independence. For the Cape Independence Advocacy Group, economic considerations weigh heavily in its quest for independence. Housing some 11% of South Africa’s population, the Western Cape produces nearly 14% of the country’s GDP and is said to be one of two provinces subsidizing the rest of South Africa financially. The province’s economy, by the group’s calculations, is the combined size of the economies of Namibia, Botswana and Zimbabwe. (It is worth adding that the Western Cape, South Africa’s premier tourist attraction, has a geographic size similar to Greece.) On the debit side of the ledger, the Western Cape is being subjected to the ‘disastrous’ economic policy followed by the ANC nationally.

The Cape Independence Advocacy Group concludes that for the province ‘there’s a net gain by not being part of South Africa’. CapeXit, the largest pro-independence organization in the Western Cape, claims a membership of over 560,000. Portraying itself as a ‘non-political movement for all people of the Western Cape, regardless of race, religion or political views’, CapeXit asserts that independence for the Western Cape ‘is legal, feasible, fair, practical, and necessary’. Independence is allowed under the South African constitution’s provision for the self-determination of language or cultural groups (article 235), it is claimed, and moreover legal under international law – even without the approval of the parent state (South Africa). The Western Cape’s separation from South Africa is also supported by three opposition political parties, namely the Cape Party and the Cape Coloured Congress (both provincially-based and very small) and the Freedom Front Plus, a predominantly Afrikaner party with modest representation in the national Parliament.

Slim chances for partition

Despite the claims of the independence movement, there are formidable political and legal obstacles to achieve a negotiated partition. First, the national constitution and that of the Western Cape Province empower the president (at national level) and the premier (of the province), respectively, to call referendums. They are not obligated to do so and are not legally bound by the results either. It seems highly unlikely that the Western Cape government, led by the Democratic Alliance, will call an independence referendum; the party, which operates nationally and promotes itself as an alternative government for South Africa as a whole, opposes independence for the Western Cape. The ANC is dead set against the fragmentation of South Africa – especially if the move is driven primarily by an anti-ANC sentiment. But even if an official referendum were to be held in the Western Cape and produce a majority in favour of partition, the chances are remote that the two houses of Parliament, with ANC majorities, will grant the constitutionally required approval for separation. A unilateral declaration of independence by the rulers of the Western Cape is also extremely unlikely because it will spark serious confrontation between the secessionists and the central government and condemn the Cape republic to internationally contested statehood.

To conclude, the chances of South Africa experiencing a new round of top-down ethno-territorial partitioning along the lines of the earlier Bantustanization design are very slim indeed. Statehood for the Western Cape may for the foreseeable future remain a desirable but unattainable dream for many people in the province (supported by considerable numbers in other provinces). The Western Cape may well remain a hotbed of anti-ANC sentiment and the Democratic Alliance and champions of independence may come to agree on seeking expanded powers for the Western Cape Province – still a tall order that will require parliamentary approval. Given its indeterminate status, Orania’s longer-term future is uncertain. The best it can realistically hope for over the short term is that its de facto territorial autonomy is treated by the ANC government in the same indifferent way that the rulers respond to the rising number of private lifestyle villages (or gated communities) catering for affluent South Africans seeking refuge from the scourges of rampant crime and dysfunctional public services.

Author: Deon Geldenhuys