Parent State’s Support for Left-behind Minorities: Some Documented Evidence from Moldova, Georgia and Serbia

When de facto states emerge, rarely do their respective authorities find themselves governing over ethnically homogenous populations in the territories they control. Some exceptions, like Northern Cyprus, exist; however, even in such cases a few hundred left-behind minorities still remain. My attempt in this piece is to cast some light on the rather unexplored area in de facto state research; namely, the extent to and ways in which parent states engage with their respective left-behind ethnic kins under the de facto state authorities and territories. At an outset, when looking at how Moldova, Georgia, and Serbia deal with their left-behind minorities, there seems to be a stark variation among them. I shall also try to give some initial hunches on why that may be the case.

Moldovans in Transnistria: A paradoxical sense of allegiance

Moldova could be said to have taken a stance of relative distance towards their left-behind minorities in Transnistria. Two main elements are crucial to understand Chișinău’s approach. Firstly, Transnistria is rather unique with Russian, Ukrainian and Moldovan populations taking an equal share in the pie of the de facto state’s ethnic composition. It is one of the rare cases where the left-behind minorities, in this case ethnic Moldovans residing in Transnistria, are not numerically inferior in relation to other ethnic minorities.

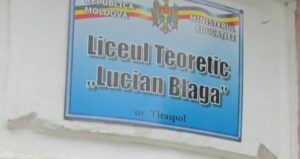

Image: “Lucian Blaga” Theoretical High School in Tiraspol is one of the few remaining educational institutions teaching in the Romanian language, on the left bank of the Dniester (Source: Ziarul de Gardă).

Moldovan policy-makers have previously focused on how to protect the linguistic and education rights of ethnic Moldovans in Transnistria. Education remains topical for Chișinău authorities who are working to maintain the last eight Romanian-speaking schools functional, while the authorities in Transnistria have already classified them as “private” institutions. Interestingly, however, Moldova’s Law No. 173-XVI, adopted on 22 July 2005, reaffirms the “humanitarian, political, socio-economic and legal support to the population of Transnistria” without specifically targeting any of Transnistria’s ethnic populations. Perhaps this speaks of Moldova’s strategy to focus on the potential to re-integrate the entire Transnistria, without ethnicizing the issue. For example, Moldova has created mechanisms to allow Transnistria (regardless of its populations’ ethnic identities) access to services on the territory of Moldova proper and, by extension, to the European network for all Transnistrian residents.

Actually, preferential treatments to Moldovan ethnic population by Chișinău can only be witnessed in territories that are under Moldova’s control, such as parts of the Dubăsari district. For instance, Moldova’s Law no.39-XVI of 02.03.2006 allows “full exemptions from the payment of the tax for state registration of the enterprise”. Similarly, with the Law no.270 of 23.11.2018 Moldova “increased by four successive salary classes” the “personnel of budget units of the left bank of Dniester”. Whereas these measures are not publicly instituted as direct support for the Moldovan “minority”, and the minority itself enjoys the jurisdiction of Moldovan state, then these people on the left bank of Dniester are not really left-behind. This raises even more questions whether Chișinău sees beyond those remaining eight Romanian-speaking schools, or not.

Ethnic Georgians in Gali: Support in exchange for loyalty?

The available documents suggest that Georgia has adopted not only an ambiguous policy towards ethnic Georgians residing mainly in the Gali district of Abkhazia, but also towards those who, having taken refuge in Georgia proper during the war (1992-93), later returned to reside in Abkhazian-held territories. The labelling of ethnic Georgians as “returnees” has reinforced the sense of both territorial and civic non-belonging to a stateless minority that has been caught between the two sides. Besides being poorly protected by Abkhazia, which fears a reverse in the ethnic balance, the Georgian authorities have often accused the returnees of disloyalty.

This was further exacerbated after the residents of Gali voted for President Sergei Bagapsh in the 2005 Abkhazian elections, and punitive measures were implemented towards Mingrelians working for Abkhazia’s local self-governments and law enforcement organs. While very seldomly mentioning and let alone engaging with their left-behind minority in Abkhazia, Georgia often attempts to discourage them from voting for Abkhazian representatives. Georgia’s left-behind minority live under a constant sense of fear of being perceived as collaborators by both sides, having to cope with being collectively guilty for the de facto separateness of Abkhazia from Georgia.

Image: Left-behind minority or neglected minority? (Source: Twitter)

Somewhat paradoxically, some ethnic Georgians from the Gali district had justified their return to Abkhazia in the face of almost no support from the Georgian authorities. The discussion around their status has been taboo, which has resulted in a significant lack of consideration for reintegration, and in the worst scenario their return to the occupied territory. International organisations reported nearly non-existent assistance and very limited and unreliable housing data. This has led to confusing situations with regard to the status granted, with many ethnic Georgians having returned to Abkhazia while retaining their Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) title.

Source: Georgians from Gali crossed the bridge to get their pensions. “We stand here to receive our pensions. Georgia pays us – it is a very small amount, but it is better than nothing” an elderly woman told reporters. (Source: JamNews)

More broadly, little is known about how ethnic Georgians living in Abkhazia are materially supported by their parent state. Regular, albeit vague, references are made to cash transfers, whether IDP allowances or Georgian pensions or to wages received by the Georgian government, particularly in the health and education sectors. The latter is one of the rare sectors where the Georgian authorities are actively supporting their left-behind ethnic minority. The Ministry of Education and Science continues to implement different programmes aimed at buttressing Gali district schools, one of the most important being the Program of Financial Aid for Teachers and Administrative-Technical Staff on the Occupied Territories which establishes financial support for the beneficiaries living on the occupied territories. Nevertheless, reports on the subject have denounced this educational financial support as being more of a symbolic character, rather than a real financial aid.

Serbs in Kosovo: Constructing a Serbian appendix in Kosovo

Serbia emerges here as an outlier. The term “Serbian patronage” has been widely used and Belgrade’s support of Kosovo Serbs has been thoroughly analysed. This support can be roughly detailed in four forms: political, financial, education and healthcare.

A stranglehold on Prishtina’s politics

Since the establishment of an international administration in Kosovo in 1999, Belgrade has increasingly started to impose itself in local and national elections. For almost about a decade now, its influence on the latter is mainly carried out through the “Serb List” political party in Kosovo which, in addition to being loyal to Belgrade, offers Kosovo Serbs political representation in Kosovo. The “Serb List” occupies all the guaranteed seats for the Serbs in Kosovo’s parliament, and leads with all the Serb-majority municipalities in Kosovo. Belgrade utilises the “Serb List” to exert overwhelming influence not only over the Kosovo Serbs but also Prishtina’s daily politics

Image: “Because there is no going back from here” reflects left-behind minority sentiments in North Mitrovica (Source: Eiki Berg)

Sustaining dependency

Belgrade finances an entire section of the service economy in the northern part of Kosovo (schools, clinics, roads, etc.), offers loans to companies willing to invest in the region, and funds local governments. Serbia ensures the payment of salaries, and until 2007 it was not uncommon for Kosovo Serb employees to receive a salary from both Prishtina and Belgrade, reaffirming the logic of “dual instrumentalisation”. This massive funding of Kosovo Serbs’ lives is obviously imbued with longer-term political objectives: to prevent Kosovo Serbs from leaving Kosovo, and therefore, to reaffirm and demonstrate the extent of the Serbian presence in the de facto state, and for politicians to maintain control through patronage networks.

Training future Serbian voices

The primary illustration of Serbia’s support in the field of education is the University in Northern Mitrovica, which in 2010 had some 9,000 students enrolled and required around €30 to €35 million annually. The support from Belgrade is even greater for primary and secondary education standing at around €45 million a year. Such support enforces Serbian language learning with programmes and text-books from Belgrade. According to international organisations, the schools are in good condition, operate properly, and cases of overstaffing have even been mentioned with many teachers coming from Serbia given the higher salaries.

Loyalty-based support: the case of healthcare

The northern part of Kosovo has been equipped with several clinics and health centres by Serbia, even in small villages, thanks to funding from Belgrade. However, medical workers are subject to a strict Serbian policy that regularly imposes loyalty checks, including mandating participation in demonstrations organised by the Serbian National Council in Kosovo, and contracts are often brief to discourage dissent. The funding of the medical field is part of a logic which reinforces a Serbian identity through dependency, and it is not uncommon that even in extremely isolated localities Kosovo Serbs refuse to go to Albanian health centres.

The objectives behind the variation in support of left-behind minorities

For parent states in general, it is difficult to consider the support, or the absence of support, for a left-behind minority as simply benevolence or disinterest. Support, at whatever level it may be, is often the means to a greater political end. It seems clear that Serbia’s influence in the north of Kosovo is to undermine Prishtina’s ability to exercise effective control over its entire territory and their state and nation building projects by artificially maintaining an ethnically-divided society. In 2008, Serbian authorities tried to sabotage the parliamentary elections by calling upon Kosovo Serbs to boycott them and using its Kosovo-based parallel structures to intimidate those who ran for office or intended to participate in elections. Whereas such support is nearly non-existent from Moldova, the same cannot be said for Georgia. Tbilisi stands out for its highly ambivalent discourse and political actions that do not appear to satisfy a desire for support and reintegration; this reaches its most paradoxical extreme given that some ethnic Georgians have sometimes chosen to return to occupied territory. The rhetoric surrounding “loyalty” from Tbilisi seems to be another crucial element to consider when assessing the level of support–much the same as in Serbia–either by requiring minorities to demonstrate their allegiance to the parent state or by launching punitive measures.

Author: Marie Beslier