Will President Trump Recognize Somaliland?

On 8 August 2025, US President Donald Trump hosted Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan and Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev at the White House for a ceremony to initial an agreement officially titled “On the Establishment of Peace and Interstate Relations between the Republic of Armenia and the Republic of Azerbaijan.” At a press conference after the ceremony, President Trump was asked if he would diplomatically recognize Somaliland in exchange for its strategic cooperation with the US. President Trump replied that “We are looking into that right now, good question actually; another complex one as you know, but we are working on that right now. Somaliland.”

Trump’s response to what was probably an unexpected question at a press conference has fueled speculation that US recognition of Somaliland is imminent. Joshua Meservey, the author of an influential 2021 report advocating for US recognition of Somaliland argues that, among conservatives, recognizing Somaliland has become almost a standard foreign policy recommendation. Perhaps the most famous example is the explicit recommendation to recognize Somaliland on p. 186 of the Project 2025 document. A few months ago, The National Interest also published an explicit call for President Trump to recognize Somaliland. High-profile US diplomatic and military delegation visits to Somaliland in December 2024 and June 2025 have also heightened speculation that US recognition of Somaliland is forthcoming.

While one can never underestimate President Trump’s ability to surprise, formal US recognition of Somaliland does not appear to be imminent. Yet, there are several reasons for believing that it might be a distinct possibility at some point during President Trump’s second term in office. First, President Trump has consistently shown himself willing to challenge orthodox or established US foreign policy consensus. Among other things, during his first term in office, he announced a “Muslim travel ban,” moved the US embassy in Israel to Jerusalem and held two summits with North Korean dictator Kim Jong Un. In the first nine months of his second term in office, President Trump has publicly berated Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky at the White House, shuttered USAID and bombed three nuclear sites in Iran. To his supporters, such moves represent bold, innovative and creative thinking. To his critics, they are naïve, reckless and dangerous. Whatever one thinks about his specific foreign policy choices, there is no doubt that overturning 34 years of established US foreign policy precedent to maintain “one Somalia” is something President Trump would do if he felt it advanced US national interests in the Horn of Africa and larger Red Sea region.

Second, President Trump has also shown a more specific willingness to question the territorial status quo. During his first term in office, President Trump recognized Israeli sovereignty over the Golan Heights and Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara. In the first nine months of his second term in office, President Trump has repeatedly expressed his interest to buy Greenland, make Canada the 51st state and retake control of the Panama Canal. He has also repeatedly expressed his openness to Ukrainian territorial concessions as part of any peace agreement between Russia and Ukraine. Recognizing a would-be sovereign state that is more peaceful and more democratic than most of its neighbors in a strategically important part of the world does not seem like something President Trump would shy away from.

Image: Somaliland’s “partly free” yellow surrounded by a sea of “not free” purple. Source: Freedom House, Freedom in the World 2025.

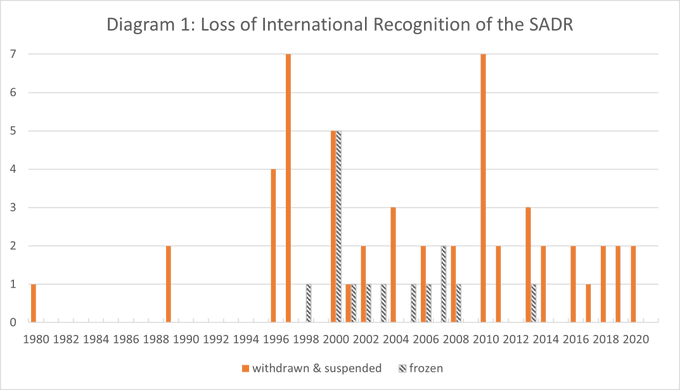

Third, President Trump’s willingness to question the territorial status quo seems to be shared by many other countries in the world today. Azerbaijan forcibly eradicated Nagorno Karabakh, Russia currently controls about 19% of Ukraine’s territory, and, more positively, several Central Asian countries recently agreed to exchange disputed territories and resolve territorial disputes between them. Ireland, Norway, Spain and Mexico have all recently recognized Palestinian statehood while France, quickly followed by Australia, Canada and the United Kingdom did so earlier this month. The argument that Somaliland has a better case for recognition than Palestine attracts support from across the US political spectrum.

Finally, unlike some of his other actions that have given rise to constitutional challenges that the president has exceeded his authority or claimed authority that he does not possess, recognition of foreign countries is exclusively a presidential prerogative. Article II, Section 3 of the US Constitution contains the so-called “reception clause” which stipulates that the president “shall receive Ambassadors,” which “is a duty that many suppose grants the accompanying power to recognize foreign nations and their governments.” This interpretation of Article II, Section 3 dates back at least to 1790 and the views of Thomas Jefferson. In conjunction with this, presidents also have the exclusive authority to terminate diplomatic relations with other states. The president’s exclusive authority to recognize foreign states and their governments was upheld in the Supreme Court case Zivotofsky v Kerry (2015). The Supreme Court’s 6-3 ruling in favor of the executive branch held that “Recognition is a matter on which the nation must speak with one voice. That voice is the president’s.” The majority opinion also held that “precedent and history support the view that the formal recognition power belongs exclusively to the President.” Thus, President Trump faces no Constitutional restraints should he wish to formally recognize Somaliland.

So, it’s safe to say that President Trump can recognize Somaliland if he wants to do so. Is there momentum for him to do so now? One source of strategic discontent within the intelligence and security communities and among the “China hawks” in both political parties is the status of the US military base in neighboring Djibouti. In 2002, the US purchased Camp Lemmonier from the French and established its first permanent military base in Africa there. Djibouti currently hosts military bases from France (1946), the US (2002), Japan (2011), Italy (2013) and China (2017). While Djibouti’s multi-base hosting strategy may reflect its neutrality, the country is widely seen within the US as being far too heavily influenced by China, with some concerns also expressed that it is far too sympathetic to Iran and the Houthis. Yet, it is important to note that US concerns with Djibouti go far beyond China having a hardened military base that is capable of hosting nuclear submarines and aircraft carriers. Several years before the Chinese arrived, Djibouti ordered the USto remove drones from Camp Lemmonier and relocate them to a much more remote location. US concerns about a Status of Forces Agreement that puts Djiboutians in charge of all aircraft control also long predate the Chinese military base. These concerns were exacerbated in May 2024 when Djibouti denied the US permission to launch strikes against the Houthis from its territory. Somaliland has long been clear that a US military base established in Berbera in the context of US diplomatic recognition of Somaliland would face no such restrictions.

Image: The view from Berbera looking across the Gulf of Aden toward Yemen. (Source: Scott Pegg).

A second major source of momentum advancing Somaliland’s status within the US political system is its 2020 formal partnership with Taiwan. Somaliland’s agreement with Taiwan was clearly designed to take advantage of the overwhelming bipartisan Congressional majorities behind the 2018 Taiwan Travel Act and the 2019 Taiwan Allies International Protection and Enhancement Initiative (TAIPEI) Act. Michael Rubindescribes Somaliland’s agreement with Taiwan as “strategically brilliant” because “it set Somaliland apart at a time when a broad bipartisan consensus had coalesced with regard to the China threat.”

Somaliland’s partnership with Taiwan caught the attention of the first Trump Administration but was most helpful in advancing its cause within the US Congress, as was the astute lobbying of Bashir Goth, its ambassador to the US. Somaliland has made progress with the US Congress in several ways. First, James M. Lindsay has argued that Congress has several “indirect means” of influencing foreign policy, one example of which is changing structures and procedures in the executive branch. There are several examples of this with Somaliland. The bipartisan 2022 Somaliland Partnership Act, for example, required “the Department of State to report to Congress on engagement with Somaliland, and to conduct a feasibility study, in consultation with the Secretary of Defense, regarding the establishment of a partnership between the United States and Somaliland.” In 2022, US Senator Jim Risch (R-Idaho and the current chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee) also introduced an amendment to the Fiscal Year 2022 National Defense Authorization Act requiring that “The Secretary of State, in consultation with the Secretary of Defense, shall conduct a study regarding the feasibility of the establishment of a security and defense partnership between the United States and Somaliland.”

Second, Congress has increasingly focused on travel to and from Somaliland. In April 2025, Somalia, in trying to please China upset the US Congress by banning Taiwanese officials from travelling through Somalia to visit Somaliland. This largely symbolic ban (Taiwanese officials would travel to Somaliland through Addis Ababa or Dubai and avoid Mogadishu entirely for security reasons) led to a furious response from the US Congress which quickly led to Somalia reversing the ban a few months later. Subsequently, US Representatives Chris Smith (R-New Jersey) and John Moolenaar (R-Michigan) sent a September 2025 letter to US Secretary of State Marco Rubio asking that the US State Department “distinguish Somaliland from the Federal Republic of Somalia in its travel advisory report” and noting that it already had separate regionally-based travel advisories for countries including Cameroon, Ethiopia and Kenya.

Finally, Congress has also engaged in more direct advocacy on behalf of Somaliland. Representatives Scott Perry (R-Pennsylvania) and Andrew Ogles (R-Tennessee) introduced the 2024 Somaliland Independence Act. Representative Perry and several other co-sponsors re-introduced the Republic of Somaliland Independence Act in 2025. Perhaps most significantly, influential Senator Ted Cruz (R-Texas) sent a letter to President Trump personally requesting that he recognize Somaliland in August 2025. Cruz’s letter was predictably celebrated in Somaliland and condemned by Somalia.

One domestic and two international developments have also arguably had some influence in advancing Somaliland’s cause in the US. Domestically, Somaliland’s successful 2024 presidential and political party elections perhaps did not massively advance its cause in the US but did at least avoid a potentially damaging blow that could have hurt its chances for recognition if the elections were not held, widely accepted or peaceful. Arguably, its 2021 parliamentary and local council elections were even more beneficial to Somaliland as they prevented its detractors from highlighting that its Members of Parliament had not been elected for 16 years. President Trump’s foreign policy has shown no interest in promoting democracy abroad, but large swathes of the US political establishment are sympathetic to Somaliland’s imperfect yet substantive embrace of democracy.

Image: Supporters of the now-governing Waddani Party campaigning during the 2021 parliamentary and local council elections. (Source: Scott Pegg)

Internationally, the impact of Somaliland’s 2024 Memorandum of Understanding with Ethiopia is hard to gauge. The Biden State Department vehemently opposed the MoU, but it did elevate the question of Somaliland’s ultimate status and force an array of diplomats and officials to educate themselves on Somalia, Somaliland and the Horn of Africa. Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s chilling rhetoric on Ethiopia’s historical destiny to reclaim access to the Red Sea preceded the signing of the MoU but resurfaced earlier this month during ceremonies marking the opening of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD). Somaliland supporter Joshua Meservey and several other commentators believe Ethiopia and Eritrea are moving toward war over Ethiopia’s desire to retake the Red Sea port of Assab which it lost when Eritrea became independent in 1993. The horrific violence and systematic human rights abuses so prevalent in Ethiopia’s civil war in Tigray and in Sudan’s civil war suggest that whatever its other limitations might be, implementing the Somaliland-Ethiopia MoU peacefully is a far better option for the international community than the massive humanitarian catastrophe that would accompany any conflict between Ethiopia and Eritrea over Assab.

A second international development, which like Somaliland’s partnership with Taiwan, is obviously designed to play well in the US political system is Somaliland’s seeming embrace of Israel and its willingness to participate in the Abraham Accords. While there are serious questions as to how much popular opposition this would generate within Somaliland society, Somaliland’s leaders seem willing to run this risk if it helps them achieve recognition from the incredibly pro-Israeli Trump Administration.

President Trump’s seemingly honest answer to an unexpected question at a recent press conference and the limited movement outside observers detect toward prioritizing formal recognition of Somaliland within his administration suggests that such recognition is not imminent. Yet, the US has fundamental concerns about its base in Djibouti, many of which could be alleviated by relocating it about 150 nautical miles down the coast to Berbera. President Trump has the unquestioned authority to make recognition decisions but is surely emboldened in his willingness to consider such a move by the explicit support of key Senators like Ted Cruz and Jim Risch, broader Congressional support more generally, Somaliland’s friendship with Taiwan, its openness to Israel and the Abraham Accords, its broadly successful democracy and, potentially, access to its oil and other critical minerals.

What would one expect if the US were to lead the world in recognizing Somaliland? Somaliland would end up with more formal diplomatic recognition than Taiwan (12 countries) but at least initially less diplomatic recognition than Kosovo (give or take 100 countries). The US would, probably, be followed by Ethiopia, Israel, Taiwan, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom and presumably several other US allies. Beyond Ethiopia, the African countries most friendly to Somaliland and thus most likely to recognize it include the Gambia, Kenya, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, South Africa and Uganda.

Somalia would certainly try to combat diplomatic recognition of Somaliland. While it lacks the diplomatic weight that China can bring to bear against Taiwan, it can probably persuade some of its allies like Egypt, Eritrea, Qatar and Turkey not to recognize Somaliland. One problem that Somaliland faces on the African continent is that the countries opposed to its recognition are far more opposed to it than its friends are in support of it. Djibouti, which has some weight as a neighboring country would almost certainly oppose Somaliland’s recognition as it is not interested in losing military bases or shipping volumes to Berbera’s increasingly efficient port. Somaliland’s partnership with Taiwan clearly indicates that China would oppose its recognition and probably use its global influence to rally other countries not to recognize Somaliland. It would certainly use its status as a Permanent Member of the UN Security Council to deny Somaliland membership in the United Nations.

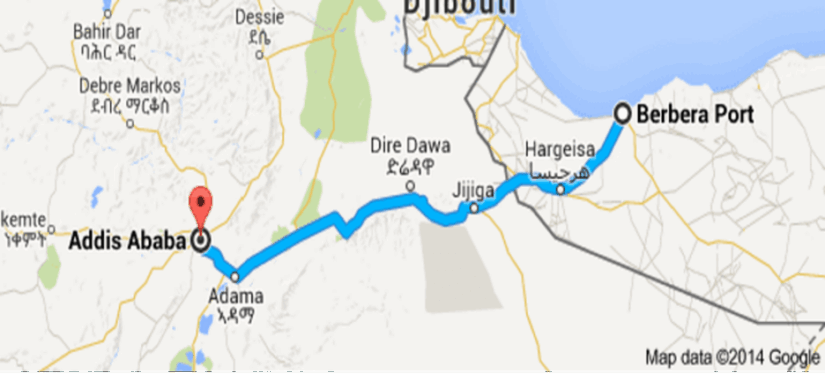

Formal recognition by the US resulting in a level of recognition like or somewhat less than what Kosovo currently enjoys would be transformational for Somaliland. Recognition in Somaliland is “accorded almost mythical status, where it is seen as the solution to all problems facing Somaliland.” Yet, recognition will not automatically improve the status of women in Somaliland, reduce widespread qat addiction, or solve global climate change which renders its livestock-based economy increasingly vulnerable to recurrent drought. Recognition will also almost certainly create new problems. The corridor linking Addis Ababa to Berbera will exacerbate the growing economic inequality between Somaliland’s central and peripheral regions. To the extent that recognition exacerbates this inequality, it is unlikely to be well received in Somaliland’s eastern or western regions.

Image: Addis Ababa – Berbera Port connection

Large-scale violence in and around Las Anod in eastern Somaliland remains unresolved. It is hard to see Somaliland society accepting the reality (as opposed to the possibility) of warm relations with Israel while Palestinians in Gaza face famine and widespread suffering. The Somaliland government of President Abdirahman Mohamed Abdullahi ‘Irro’ is obviously calculating that recognition is the number one thing that most Somalilanders want and that they will accept some of the various trade-offs that will inevitably come with it. President Trump may yet provide ‘Irro’ with the opportunity to put that logic to the test.

Author: Scott Pegg

Note: The author would like to thank Joshua Meservey and Michael Rubin for generously sharing their thoughts with him.