The Somaliland-Ethiopia Memorandum of Understanding: Transformational Game Changer or… Not So Fast?

Earlier this month, Bashe Awil Haji Omar, the chairman of the technical committee charged with implementing the memorandum of understanding (MoU) signed by Somaliland and Ethiopia declared that the first phase of the committee’s work had been completed. One can take him at his word and yet profound unanswered questions about what this MoU entails and how likely it is to be implemented remain.

The MoU was signed on 1 January, 2024. To date, its full text has not been released and the lack of concrete details surrounding it has fueled concern. The basic components of the MoU seem to be that Ethiopia secures commercial access to the port of Berbera in Somaliland and 20 km of land around Lughaya (west of Berbera) where it can establish a naval base under a long-term lease. In return, Somaliland would secure an ownership stake in Ethiopian Airlines or Ethio Telecom and either formal recognition of its sovereignty or the prospect of such recognition from Ethiopia.

Image: Map of Somaliland

Were this deal to be fully implemented, it would be a transformational game changer for Somaliland, secure landlocked Ethiopia’s long-term goal of reliable access to the sea and produce significant repercussions throughout the Horn of Africa. One way to evaluate the prospects for the Somaliland-Ethiopia MoU is to look at it from the perspective of the two leaders who signed it, Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed Ali, and Somaliland’s President Musa Bihi Abdi.

Prime Minister Abiy thrives on grand gestures. Early in his term of office, many of these headline-grabbing initiatives like appointing women as fifty percent of his cabinet, freeing political prisoners, and, most notably, making peace with Eritrea(which won him the 2019 Nobel Peace Prize) were greeted with widespread international enthusiasm.

More recently, several of his bold actions have produced disastrous consequences, most notably the war in Tigray which has featured widespread crimes against humanity and ethnic cleansing, the systematic use of rape and sexual violenceand continuing atrocities after a ceasefire was signed in 2022. In addition to the war in Tigray, Ethiopia’s regions of Amhara and Oromia have also seen significant violence. Reducing Ethiopia’s overwhelming dependence on the port of Djibouti, securing access to the sea and ending Ethiopia’s landlocked status since 1991 (de facto) or 1993 (de jure) after Eritrea’s secession and doing so peacefully would be a historic and wildly popular achievement for Abiy.

Somaliland’s President Bihi has faced some significant crises, not necessarily of his own making like a devastating fire that destroyed Hargeisa’s central market and recurrent drought in Somaliland’s eastern regions, although his government is criticized for its ineffective response to the drought. Voters expressed their dissatisfaction in Somaliland’s 2021 parliamentary and local council elections which saw President Bihi’s ruling Kulmiye (Peace, Justice and Development) Party lose control of the lower house of parliament to an opposition coalition of the Waddani (Somaliland National Party) and UCID (For Justice and Development) parties. Kulmiye also lost control of local councils in five of Somaliland’s seven largest cities.

Image: Reading election results out in Somaliland’s 2021 elections (Source: Scott Pegg)

The 2021 elections also sowed the seeds for arguably the two biggest crises President Bihi has faced. Article Nine of Somaliland’s Constitution mandates the existence of three political parties. While this restriction was designed to promote cross-clan alliances, it is increasingly criticized as being anti-democratic. Legal and established principle holds that those three parties should be open to competition from new entrants (“political associations”) in local council elections every 10 years, nominally meaning every two terms. With the previous local elections having taken place in 2012, that 10-year mandate was due to expire in 2022, creating an incentive for the three current parties to get the local council elections out of the way in 2021, in the hope that this would consolidate their status as parties for at least another five years until the next local level elections are due. Yet, this decision created additional problems for holding presidential elections originally due in 2022.

Somaliland faced a constitutional crisis in that President Bihi’s term was supposed to expire in December 2022 yet it had no parties currently holding a constitutional mandate to contest the election and no process agreed by which to establish that mandate. President Bihi’s initially preferred solution was the highly unusual mechanism of an election that solely decides which three associations win the right to operate as parties. The president’s plan was to hold that election before a subsequent presidential election. However, the opposition parties were deeply unhappy with that proposal, seeing it as a measure that would have made it possible for President Bihi to influence the establishment of new groupings before the existing opposition parties had the opportunity to contest the presidency. The opposition parties preferred presidential elections first and party elections after that.

Frustration with perceived electoral delays and the fear that the Guurti (upper house of parliament) would extend President Bihi’s term by two years resulted in in a series of protests in Hargeisa, Burco, and Erigavo that ultimately led to the deaths of at least five demonstrators on 11 August 2022. The electoral crisis worsened when a leading figure in the opposition Waddani Party, Abdifatah Abdullahi Abdi “Hadrawi” was assassinated in Las Anod in December 2022. Hadrawi’s assassination set off a series of protests. On several occasions, soldiers opened fire, killing at least 10 protesters. President Bihi’s subsequent declaration that “terrorists” were to blame for the violence in Las Anod further inflamed opposition to his administration there.

As Markus Virgil Hoehne emphasizes, “It is hard to imagine a compromise at the moment” as two fundamentally different visions are clashing. In Hoehne’s explanation, in Somaliland’s central core triangle bounded by Hargeisa, Berbera and Burco, the “state administration had grown into an effective factor of ordering ordinary people’s lives.” In contrast, in large swathes of Somaliland’s eastern regions, no state (Somaliland, Puntland, or Somalia) has taken root and people are used to self-governance “administered by local traditional authorities, clan leaders and sheikhs.” The Bihi Administration views the problem in Las Anod as territory that needs to be controlled by the government. The local population largely opposes Somaliland and wants to be left to its own self-governance by traditional leaders.

On some estimates, the ongoing crisis in Las Anod has resulted in at least 150 dead, approximately 600 wounded, and 185,000 people displaced. The violence in and around Las Anod has been widely condemned by many of Somaliland’s international partners including in joint statements coordinated through the US State Department and the United Nations Assistance Mission in Somalia (UNSOM).

Thus, it is in the context of these dual and somewhat overlapping electoral and Las Anod crises that President Bihi’s active promotion of the Somaliland-Ethiopia MoU needs to be considered. The electoral crisis has seemingly been resolved by all three political parties agreeing to hold simultaneous presidential and political party elections on 13 November 2024, albeit with the decision not to hold elections in the four districts of Buhodle, Hudun, Las Anod, and Taleh – thus disenfranchising voters there and further fraying their ties to Somaliland. This also marks a significant reversal from the 2017 presidential election when voters in Hudun, Las Anod, and Taleh were able to participate.

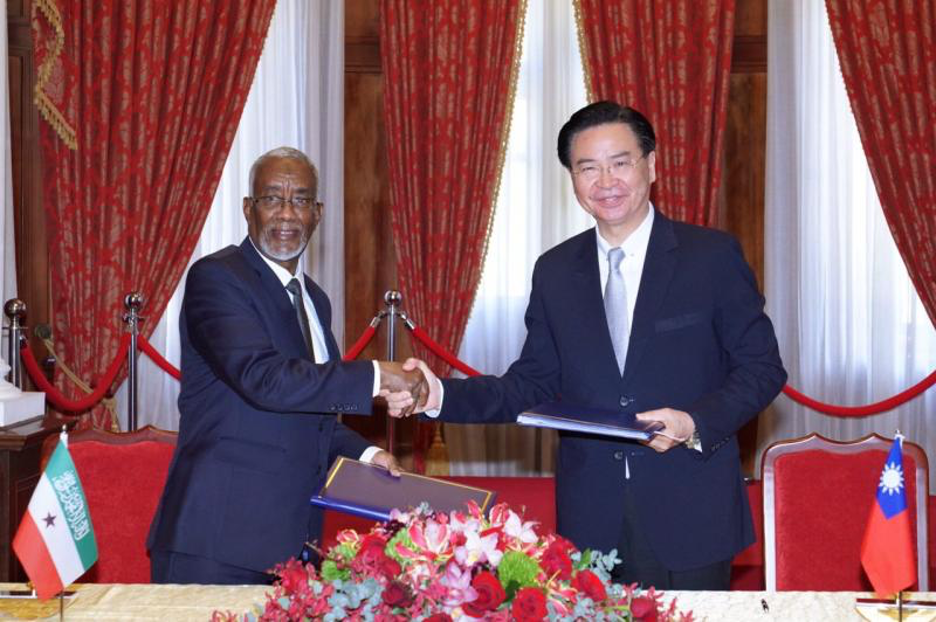

President Bihi won the 2017 presidential election with 55.1% of the vote. Given Somaliland’s clan-based politics, he could win re-election in a free and fair election in November 2024 even given the various crises described above. Additionally, President Bihi has some foreign policy accomplishments. Somaliland and Taiwan established reciprocal representative offices in 2020 and their partnership has flourished. Somaliland’s foreign relations have perhaps advanced furthest with the United Arab Emirates. In 2019, the UAE received President Bihi with full state honors. The UAE posted its first representative to Somaliland in 2021 and Somaliland maintains a mission in the UAE. The UAE also signed an extensive bilateral agreement in 2023 that, among other things, grants Somaliland citizens the right to work in the UAE.

Yet, in the context of Somaliland politics, such forms of “engagement without recognition,” however many tangible benefits they generate, pale into insignificance when compared to the primary goal of formal recognition of Somaliland’s sovereignty. As I have argued elsewhere, “In the popular imagination in Somaliland, recognition is accorded almost mythical status, where it is seen as the solution to all problems facing Somaliland.” While other de facto states have shifted their goals over time, Nina Caspersen notes that Somaliland has remained steadfast in its pursuit of sovereign recognition.

One can point out that recognition will not solve several major problems in Somaliland (widespread qat addiction, high dependence on livestock exports in a drought-prone region, the poor status of women) and might create some new ones, but none of that matters. Recognition is the number one thing that most Somalilanders want. If President Bihi can secure formal recognition from Ethiopia before the November 2024 elections, that would guarantee his re-election and cement his historical legacy as the president who achieved what none of his four predecessors in office could do. By contrast, that part of the MoU falling apart could severely damage Bihi’s re-election prospects.

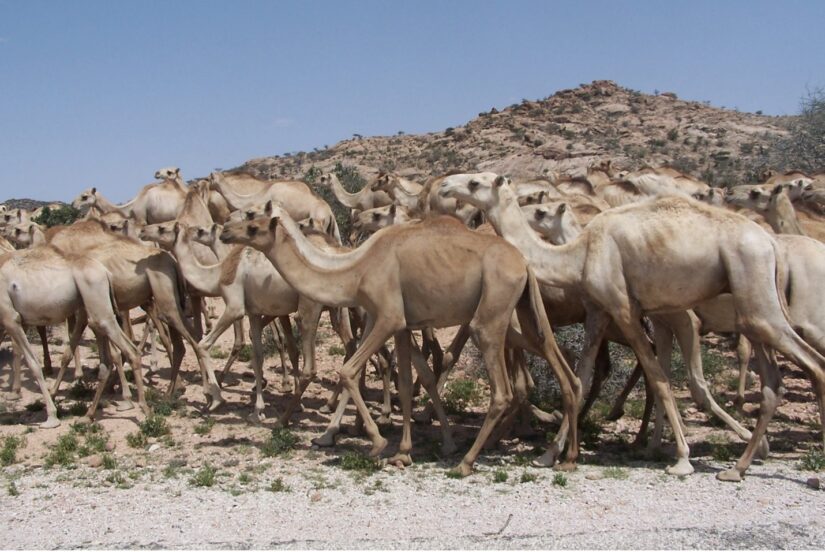

Image: A herd of camels being driven to Berbera (Source: Scott Pegg)

Can he pull it off? Parts of the MoU are old or established and make commercial and geographic sense and will almost certainly be implemented. Berbera and Zeila on the Gulf of Aden have been used as ports for caravan-based livestock trade since the early 1900s. Musa, Stepputat and Hagmann demonstrate that “revenues from livestock trade have been an integral part of Somaliland’s state building process since the early 1990s” and emphasize that the livestock trade has been one of the most heavily taxed sectors in Somaliland. Having a modern port at Berbera connected by good roads to Hargeisa and then onto Ethiopia has been one of Somaliland’s longest-held aspirations. Yet, for many years, the Berbera Corridor was mostly just a dream.

Image: The main road from Berbera to Hargeisa in 2010 (Source: Scott Pegg)

Stepputat and Hagmann noted that in 2018, “the 225 km road from Berbera Port to the Ethiopian border was full of potholes, and passage through Hargeisa highly congested.” That has changed significantly in the past several years. In 2021, the last time I travelled from Berbera to Hargeisa, at least 90+% of the road was wide, smooth, and paved. The bypass around Hargeisa was still being constructed but the idea that large trucks could soon be carrying goods to Ethiopia no longer seemed a fantasy. Significant progress on the port renovation has been made. The container terminalhas massively expanded its capacity and the associated economic zone now features modern warehouses and offices.

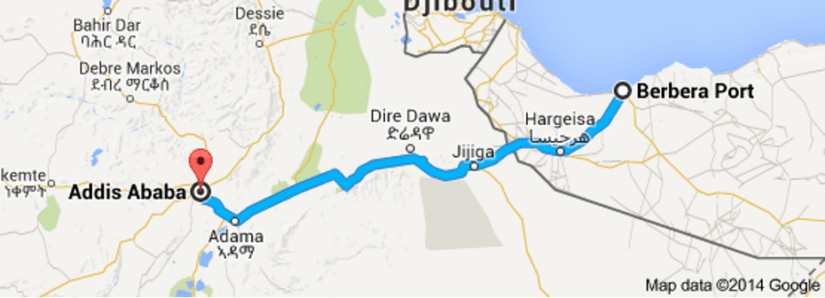

Image: Addis Ababa – Berbera Port connection

Ethiopia learned the risks of over-dependence on one port when it lost access to Assab in what is now Eritrea. It does not want to depend on Djibouti for more than 95% of its imports. Prime Minister Abiy has been blunt that “150 million people cannot reside in a geographical prison.” Berbera was previously not able to serve as a viable competitor to Djibouti. It is either now in or about to arrive at that place. Berbera also has significant geographical advantages over other potential competitors. Djibouti is slightly closer to Addis Ababa at 770 km of driving distance than Berbera is at 921 km. Yet, Berbera is closer to Addis Ababa than other potential port competitors including Assab (951 km), Mogadishu (1416 km), Kismayo (1627 km), Mombasa (1813 km) or Port Sudan (1822 km). Berbera is also far closer to Dire Dawa (Ethiopia’s second largest city, 468 km) than other competitors except Djibouti (318 km). Beyond the compelling commercial, geographic and diversification benefits of using Berbera’s port, Ethiopia and Somaliland have generally had friendly relations with Ethiopia serving as what Kosienkowski and Rundincová have characterized as a “quasi-patron” state for Somaliland.

Thus, the commercial access to Berbera port part of this MoU will almost certainly happen and it will transform Somaliland’s economy. Like many emerging states in Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries, the US and Latin America in the 19th century and much of post-colonial sub-Saharan Africa, Somaliland has relied extensively on international trade taxes to funds its administration. In developing the Berbera Corridor, Somaliland is choosing to forego customs revenue in the expectation “that ‘more movement’ will promote development and increase state revenue ‘further inland’ to substitute revenue from customs.”

The new, different, and controversial part of the MoU is Somaliland’s exchange of 20 km of coastline near Lughaya to Ethiopia for use as a naval base in return for Ethiopia’s recognition of Somaliland’s sovereignty. This part of the deal may never happen. Indeed, exactly what Ethiopia has agreed to do here remains the most pertinent open question surrounding this MoU. Somaliland’s President Bihi was unambiguous at the signing ceremony as to what had been agreed: “we will let them have those 20 km of our seaside and [in return] they will recognize us as an independent state immediately.” Somaliland’s Foreign Minister Dr. Essa Kayd was equally explicit a few weeks later in stating that without recognition, “nothing is going to happen.”

Yet, the Ethiopian government suggested far less had been agreed to. In an official statement on 3 January 2024, the Ethiopian government only acknowledged that the MoU “includes provisions for the Ethiopian government to make an in-depth assessment towards taking a position regarding the efforts of Somaliland to gain recognition.” Put bluntly, if all this MoU entails is an “in-depth assessment,” it means nothing. As James Ker-Lindsay has argued, a state like Ethiopia can establish a very high threshold for the level of engagement without recognition it is willing to entertain with a de facto state like Somaliland but as long as it keeps insisting it has not recognized that state, then it has not done so.

Ethiopia’s reticence on formal recognition is perhaps exacerbated by a furious international reaction to the MoU that is reminiscent of the international response to Iraqi Kurdistan’s 2017 independence referendum. While the negative reaction from the Iraqi parent state and its immediate neighbors Iran and Turkey was to be expected, the harsh response from the Kurds’ erstwhile ally the United States was perhaps more surprising. In the case of the Somaliland-Ethiopia MoU, the parent state Somalia declaring the agreement “null and void” surprised no one. One day after the MoU was signed, the European Union issued a statement of concern, followed a day later by the US State Department expressing its support for the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Somalia. The Arab League expressed its support for Somalia’s territorial integrity a few weeks later, followed quickly by the African Union and the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD). The United Kingdom expressed its concerns to the UN Security Council in February 2024. Prime Minister Abiy has not been afraid to take bold leaps or large gambles before but the vehemence and unity of the international opposition to the MoU might give him pause for concern before moving forward with this aspect of it.

There are other reasons to suspect this part of the MoU might not come to fruition. First, we have seen wild speculation on Somaliland trading naval bases for sovereign recognition before. In 2018, there were rumors that Russia would recognize Somaliland in exchange for a naval base at Zeila. The UAE signed an agreement to establish a military base in Berbera but then backed out and turned its would-be base into a civilian airport. Inevitably, unfounded and illogical speculation about Taiwan wanting to establish a military base in Berbera accompanied its partnership with Somaliland in 2020. Somaliland news is rife with other unsubstantiated rumors like Kenya Airways establishing direct flights from Nairobi to Hargeisa that somehow never materialize.

Second, establishing a naval base near Lughaya would likely take Ethiopia at least 10-15 years. This doesn’t mean it won’t happen, but it does mean that there is a lot of time for Ethiopia to make its “in-depth assessment” of Somaliland’s case for sovereign recognition before locking itself into this aspect of the MoU. President Bihi might face a different sense of urgency given Somaliland’s electoral timetable, but Prime Minister Abiy need not adhere to that. In short, the commercial aspects of Ethiopia’s expanded use of Berbera’s port are coming, and they will have significant impacts on Somaliland’s economy and its domestic politics. The sovereign recognition for naval base part of the deal remains highly speculative.

Author: Scott Pegg